Women’s work

Tate Britain group show of women artists spans 400 years to 1920, as John Evans reports

Thursday, 23rd May 2024 — By John Evans

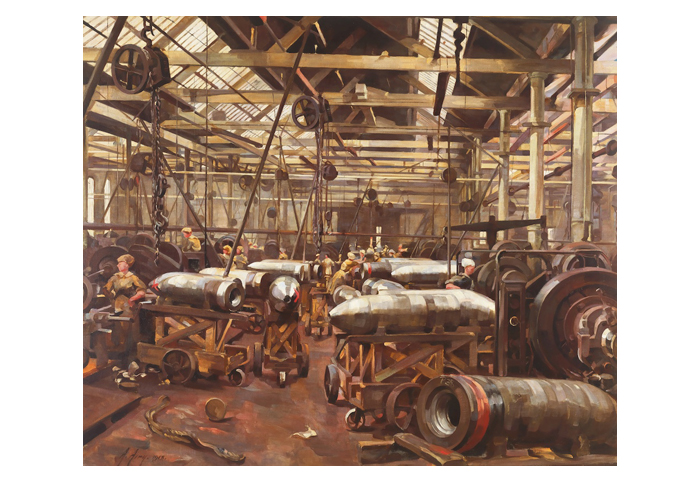

Anna Airy, Shop for Machining 15-inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow 1918, oil on canvas, 182 x 213cm Imperial War Museums

THE first public art exhibition in Britain was in 1760, the Tate tells us in notes for its new show, Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920*.

But in revelatory tone it also estimates 900 women displayed their work publicly here between 1760 and 1830.

It is now part of Tate Britain’s stated mission, going forward, to champion work by hitherto “neglected and under-represented” artists; in this case it’s women, specifically charting “the period in which women were visibly working as professional artists, but went against societal expectations to do so”.

Curators Tabitha Barber and Tim Batchelor have bought together 200 plus paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs and “needlepaintings”, and list over 100 artists here in all.

And the exhibition openers are Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c1652).

The former and Mary Moser (1744-1819) were the only women to be Royal Academy founding members in 1768, but they were specifically excluded from its council meetings and it would be another 150 years for the next woman to be elected to membership.

Gentileschi’s feted self-portrait as the allegory of painting is on loan here from Charles III as well as her Susanna and the Elders (c1638-40), newly attributed, having also been “discovered” after misattribution.

But these headliners, together with the “poster girl” painting as one expert ironically termed the Gwen John (1876-1939) self-portrait used for the show publicity, are just a small part.

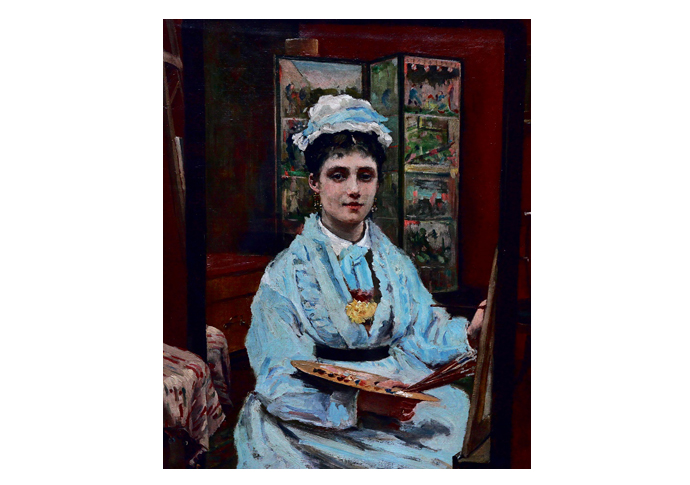

Louise Jopling, Self-Portrait Through the Looking-Glass, 1875, oil on canvas, 53.3 x 45.7cm Tate

The untold stories come from all angles, and are accompanied by a wealth of detail concerning why many of the featured artists are not household names today.

The exhibition looks at the history of life drawing, for example, and the exclusion of women from the discipline, petitions to the RA on the subject, and the important role of the Slade as the first school of fine art, which from 1871 aimed to offer women students equality of opportunity.

But the range of the works speaks more powerfully than any narrative. True, it’s suggested that Mary Moser’s reputation lost out because of her floral paintings, but few of her works survive in any case.

Thabita Barber suggests, in a comprehensive catalogue, that across the centuries a succession of women forged successful careers. Yet while many were recognised in 17th and 18th century accounts of artists, she notes: “It seems it was in the twentieth century, when art history became a discipline, that women were related to paragraphs and footnotes.”

Among the highlights of this wide-ranging and mixed group show are paintings by Mary Beale (1633-99) which include a portrait of her son and self-portraits. And Manchester-born Louise Jopling (1843-1933), who painted A Modern Cinderella, exhibited at the RA in 1875 and a related self-portrait, Through the Looking Glass.

Larger scale oils, such as The Roll Call, with its military theme, by Elizabeth Butler (1846-1933) and Colt Hunting in the New Forest by Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869-1958) challenged any notion that women’s works should be excluded for lacking impact.

Rarely seen watercolour on ivory miniatures are also on loan from Charles III’s collection.

And among the later works, alongside the Gwen John are powerful coast scenes by Laura Knight (1877-1970) and a striking oil by Anna Airy (1882-1964) of the Singer shell factory in Glasgow, from 1918.

* At Tate Britain, Millbank, SW1P 4RG until October 18. www.tate.org.uk