Why Myra was much more than the ‘Queen Mother of classical music’

With a grace that was rarely matched, Myra Hess single-handedly changed Britain’s musical landscape, writes Michael Church

Thursday, 10th April 2025 — By Michael Church

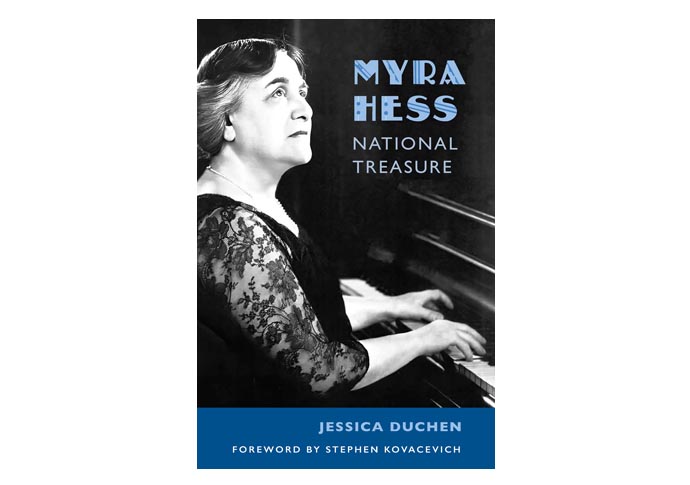

Myra Hess, the subject of a new book about her life

THE high point of my youthful concert-going was a piano recital at the Royal Festival Hall in 1959 by Myra Hess, regarded by some – unfairly in Jessica Duchen’s view – as classical music’s equivalent to the Queen Mother. Her playing was indeed regal, but it had a gracefully expressive profundity that has rarely been matched.

The last item in her programme was Beethoven’s visionary penultimate sonata, and when we bayed for an encore, her refusal brooked no reply: “How can I possibly add anything to that wonderful music?”

Jessica Duchen is too young to have heard Myra live, but she more than makes up for that with a background that in some ways mirrors that of Myra, who grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family in South Hampstead where she lived all her life.

Duchen’s book is fascinating on many levels. It offers a rich slice of music history, showing how the pianistic scene developed, chronicling British and American concert-going in the First and Second World Wars, and revealing the important part Jewish musicians played in those times.

But the book is also a colourful piece of 20s social history, covering everything from fashionable intellectual Bohemianism (Myra seemed to know everybody who was anybody), to the wartime campaign in support of Jewish refugees (for whom Myra was a lobbyist).

Yet this is at the same time an energetically researched biography of a remarkable woman who single-handedly changed Britain’s musical landscape. Jessica’s Duchen’s great achievement is to have woven all these elements into a very entertaining narrative.

An early photo of Myra, born in 1890, shows a determined little figure, which chimes with the facts of her nascent career. In later life she insisted that she’d never been a prodigy, but she was certainly precociously talented (with the Jewish Chronicle proudly following her progress), and at 13 she enrolled at the Royal Academy, where she had the luck to find a brilliant and devoted teacher.

For a pianist, getting launched in Edwardian times usually required influential connections, which the teenage Myra didn’t have, and her family weren’t rich. At 17 she launched her career as a pianist by engaging an orchestra, a conductor, and a venue herself, though the all-important Times review which resulted was patronising. Earning her living by teaching, and knocking about with painters, poets, and suffragettes, she gradually made her name, with her first big pianistic breakthrough coming in the Netherlands.

An even bigger breakthrough came when she started regularly touring to America, where she and her audiences commenced a 30-year mutual love affair. But a spark was also lit by the runaway success of a little piece she had written as an experiment.

She’d fallen in love with a Bach chorale entitled Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, which she skilfully transposed for piano, and the unexpected result was a mega-hit, which set off a vogue for other transcriptions by other pianists.

Her arrangement of Jesu, Joy is still routinely played as a concert encore today.

Meanwhile, regularly playing chamber music with celebrated soloists, and now armed with a CBE (later upgraded to a Damehood), she found her name would open doors. And when war broke out with Germany in 1939, one very big door opened. Under German attack, her first thought was to berate the BBC for failing to broadcast music which could lift people’s spirits. Receiving no reply, she began touring to badly Blitzed small towns, but she also had a brainwave. Since the National Gallery had sent its paintings out of town for safe keeping, why not stage a concert or two in its now-empty shell?

Its director Sir Kenneth Clark, who happened to be one of Myra’s fans, leapt at the idea. But not just one or two concerts, he said. One every day! The rest is history. For the next six years, Myra and her fellow musicians performed in that gallery to a capacity crowd every weekday. When a bomb fell on the building, they simply moved down to the basement and carried on. “I choose every programme, and every artist, and I hardly have time to sleep,” she explained.

When the war was over, she assumed the concerts could carry on, but was defeated by the fine art brigade who wanted the uppity musicians to get off their turf. That didn’t prevent Myra continuing her leading role in Britain’s cultural life: she became a key member of CEMA – Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts – which morphed into the Arts Council. And she went on playing.

Myra fans will devour the concert programmes, reviews, performance fees, and the high-spirited letters that punctuate this story, and the personal portrait which emerges is a complex and interesting one.

Her friendships were passionate and sometimes stormy, notably that with the famous pianist Harriet Cohen, who set herself up as Myra’s perennial rival; Duchen registers Myra’s unforgiving rift with her father who tried to persuade her to go down-market and make money, and she details the Soviet-style un-personings which she inflicted on her enemies.

She was a born leader, a convivial clown, and the life and soul of a party, yet she suffered from acute pre-performance nerves, which she had to allay with the aid of card games. But there was no self-doubt in her playing.

• Myra Hess: National Treasure. By Jessica Duchen, Kahn and Averill, £40