Voice male

Soho is at the heart of Mark Bowles’ debut novel. ‘There is no place quite like it in the country,’ he tells Maggie Gruner

Thursday, 21st November 2024 — By Maggie Gruner

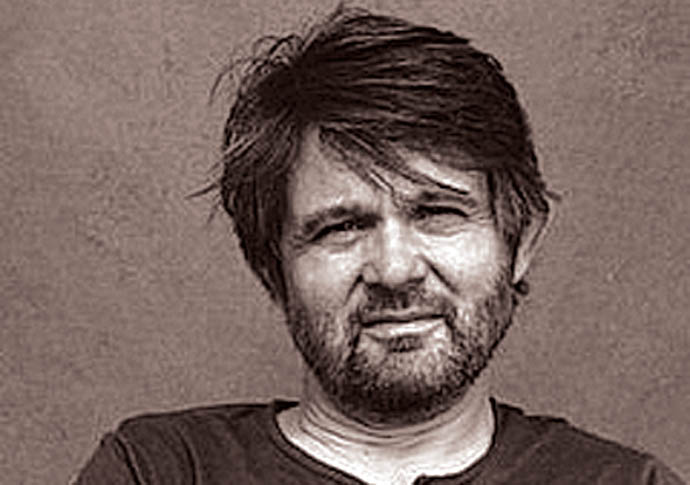

Mark Bowles

WATCH OUR ONLINE POLITICS CHANNEL, PEEPS, ON YOUTUBE

ON a dark December morning in Soho, a man views the streets through his grandfather’s welding goggles, which lend “an old-world, blood-orange tint”. This perspective suits the man, Henry Nash, who is at odds with many aspects of contemporary life. He is the prickly narrator in Mark Bowles’s compelling debut novel, All My Precious Madness.

Written as a monologue, it is a voyage inside Henry’s head. An academic and author, he writes in a small Italian café in Berwick Street. This habit mirrors that of Mark, who wrote most of the book in a café – Bar Termini in Soho’s Old Compton Street.

He told Review he found the café “a really congenial place to write”.

Henry also finds the café congenial – until a man who runs a digital consultancy and marketing company starts frequenting the place.

This man, who Henry names Cahun, blathers loudly into his phone about his travels, and a spiel of tech-related business jargon.

Increasingly irritated by Cahun, who represents much of what he hates, Henry vents his spleen on business jargon, obsession with making money, selfie sticks and narcissism.

He lambasts destruction of old buildings in London, the stranglehold of social class, bullies, “blokeishness”, and people who drink coffee in takeaway cups inside a café – the cup a symbol advertising their “busy schedule”.

There’s humour and poignancy along with Henry’s growing rage. His torrent of language, bristling with anecdote and imagery, tugs us urgently through a narrative permeated by memories, particularly of his father. The latter was violent, beating the child Henry. But the father changes, and the father-son relationship is a moving aspect of the story.

Henry leads an “eccentric” life in his flat in St Anne’s Court, Soho, close to the café where he likes to write because he prefers to be “outside myself”.

He bewails the fact that “revered” institutions, such as the old Italian in Bateman Street with the 1930s espresso machine, are becoming extinct in a grab for profit.

He declares of Soho: “It is only here that I can live, in the whole of England, in this small square that will no doubt soon be eliminated like all the rest.”

Mark is also a Sohophile. He said: “I have always loved Soho. It seems such an incredibly mixed and tolerant space. There is no other place quite like it in the country.”

He met his wife – actor and singer Gemma Goggin, who has appeared in the West End’s Mamma Mia! – in a Soho pub.

The novel’s Henry thinks that in Soho he has discovered his little bit of Europe, and Italy in particular.

He comes from a working-class background in Bradford and went to Oxford, where he felt alienated. He complains that “in England, everything is stained by class and bears its accent”.

Henry completed his thesis at Birkbeck, Bloomsbury, and teaches at an American satellite university in London.

Studying for the thesis followed a decade working in a telesales office, a “hell of money and the pursuit of money” near Plaistow.

He rails against blokeishness and laddishness – men who make disgusting comments about women and “measure each other against the Ideal Geezer”, as in: “He had a two-pint lunch then comes in and closes a deal.”

Henry rages about a bully from his childhood, who forced another boy to eat dog excrement, and fantasises about violently confronting the bully, indignant that people like him “are everywhere, walking free and regarded as normal human beings”.

A champion of children, Henry has it in for people in this country who “hate” them, scowling and tutting at their behaviour in public places.

His father’s violence departs after a breakdown, and in the 10 years between his retirement and death “pockets of eccentricity and kindness were opened”.

Henry regrets not telling him he loves him, and always carries his father’s silver lighter, which he cannot throw away because it is part of his soul.

A tight string of anger in his father snapped, changing him, and a similar string in Henry seems to break after a shocking and cathartic climax – to which he wears the welding goggles.

Finally there is a lyrically described calmness and an uplifting ending.

Mark said there’s “quite a lot of overlap” between him and Henry. He grew up near Bradford and was a postgraduate at Oxford. He taught undergraduates at an American university’s satellite college in London, and he spent “too many years” working in telesales.

He wrote the book on days off, and early mornings before going to the office.

Like Henry, he loves good coffee. “Writing always surprises me,” he explained. “Themes emerge that I couldn’t have anticipated. Some of the violence, some of the rage, and expression of that, was quite surprising.”

He has formerly lived in Fitzrovia, Archway and Tufnell Park and worked in Waterstones, Hampstead, for a while.

Now the father of two lives in Brockley, south London, with his family, and is a teacher at a school in Greenwich. His unconventional novel digs deep into meaning while taking irritations many of us share by the scruff of the neck and giving them a good shaking.

• All My Precious Madness. By Mark Bowles, Galley Beggar Press, £10.99