Vis à vis Vic: the man whose work inspired Les Mis

In the latest of his series on eminent Victorians, Neil Titley turns his attention to the author of the original novel on which the world’s longest-running musical is based

Friday, 29th August 2025 — By Neil Titley

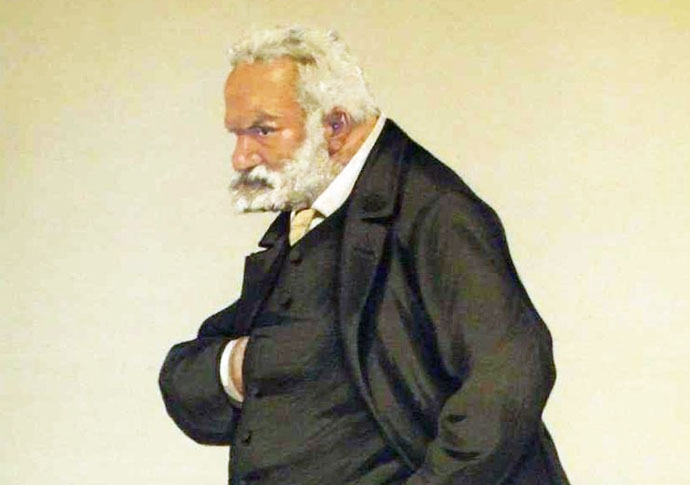

How Vanity Fair saw Victor Hugo in 1879

WHEN Les Misérables opened in the West End in 1985, it received some awful reviews – “witless and synthetic” (Observer), “sentimental old tosh” (City Limits), etc. Forty years on, it is now the world’s longest running musical.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885), the author of the original novel on which it is based, was a man much accustomed to negative reactions. He was a political animal all his life.

Although born the son of a Napoleonic general, his obvious intelligence swiftly established him as a confidante of the restored French monarchy of King Louis-Phillippe.

In 1831, after braving the church towers to research the subject (he suffered badly from vertigo), Hugo published The Hunchback of Notre Dame, becoming overnight the most famous living writer in Europe. In 1837, he was created Viscount Hugo.

Despite these favours though, he gradually became convinced of the case for socialism and rejected his own past allegiances. He once said: “Not to believe in the people is to be a political atheist.”

When the “middle-class monarchy” of Louis-Phillippe was overthrown in 1848, Hugo was persuaded to stand as mayor of his Paris arrondissement. In this new role he was at the heart of the action, storming barricades, directing troops, and taking prisoners.

Oddly enough, the only time his life was in serious danger was two years later when he attended the funeral of his fellow writer Honoré de Balzac. The horses pulling the hearse slipped and the cart slid back pinning Hugo to a tombstone.

“Thankfully, a man clambered on to the tomb and hoisted me up by the shoulders. Otherwise, I should have presented the curious spectacle of Victor Hugo killed by Honoré de Balzac.”

In 1851, he greeted the usurpation of power by Emperor Napoleon III with well-publicised fury and was forced to flee France for the safety of England.

His attitude to his new abode was not a happy one. His first words on seeing London were: “How the hell do we get out of here?”

Neither was he impressed by the English attitude to political refugees, claiming that the policy was “Let them in and let them starve.”

Finally, he found an acceptable refuge in the Channel Islands, where he was to stay in exile for 19 years.

In 1862 he published Les Misérables, described as “the Magna Carta of the human race”.

When Hugo wanted to find out what his publishers thought of his initial manuscript, he sent them a note reading simply: “?”

They replied with equal brevity: “!”

He continued to be a thorn in the side of nationalism, be it French or English. He was enthusiastically in favour of the creation of a “United States of Europe” declaring that “a war between Europeans is a civil war”. He even suggested a single currency.

When Napoleon III fell during the Franco-Prussian War, Hugo was finally allowed back into France. His home in Paris became a magnet for admirers including such luminaries as the fairy-tale writer Hans Christian Andersen.

When Andersen asked him for his autograph, a suspicious Hugo became worried that Andersen might misuse his signature to forge an acknowledgement of debt or something of the sort.

To prevent such skulduggery, he squeezed the words “Victor Hugo” into the extreme right-hand top corner of the page so that nothing could be inserted above it. Andersen left the house, still puzzling over his autograph book.

Hugo’s funeral in 1885 was a major event. Over two million people, larger than the entire population of Paris, followed the coffin to its resting place in the Pantheon. A large carnival had been held the previous night and thousands of mourners had indulged in mass public copulation in the parks of Paris.

This unusual accompaniment to the obsequies may well have been a tribute to Hugo’s other great talent, that of sexual athleticism.

Hugo had an insatiable desire for sex – “To love is to act” – and his boast that “women find me irresistible” was amply borne out.

Exhausted by his demands, his wife Adele agreed to settle for other lovers. She became the mistress of the critic Charles Sainte-Beuve (who would visit the Hugo home disguised as a nun), while Hugo acquired an actress and courtesan named Juliette, described by Charles Dickens as “a woman who looks as if she might poison his breakfast any morning when the humour seized her”.

On his return to Paris after the 1870 siege, he found a constant succession of lovers among the young actresses who auditioned for his plays. After a day of sex with these girls, each night he would return home to find another group of women, street prostitutes mingling with society ladies, waiting for him.

His numerous encounters provided him with much of the information about life in the gutter that he needed for his novels.

When Hugo was 81 years old his small grandson accidentally walked into his grandfather’s bedroom to find Hugo making love to a young laundress. Hugo stopped for a moment to proudly exclaim: “Look, little Georges, this is what they call genius!”

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. www.wildetheatre.co.uk Available at Daunts, South End Green