Twain spotting: ’The Lincoln of our literature’ in London

In the latest in his series on eminent Victorians, Neil Titley turns his attention to the ‘people’s author’ – Mark Twain

Friday, 8th August 2025 — By Neil Titley

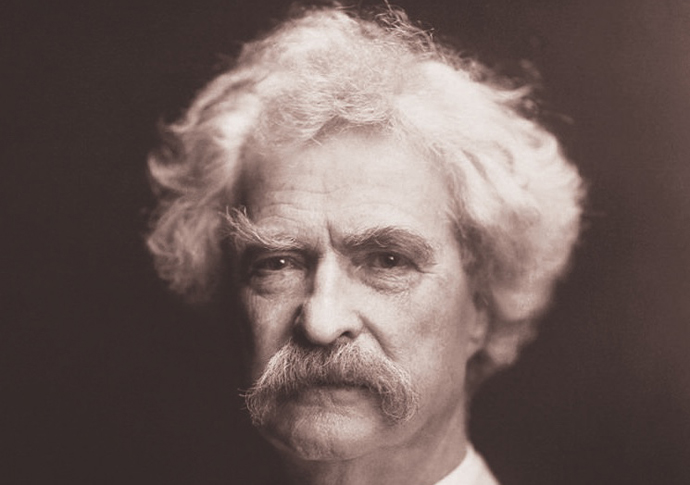

Mark Twain photographed by AF Bradley

OFTEN the subject of derision from Private Eye – the mundane rivalries of Neasden and Dollis Hill football teams epitomising its concept of dreary suburbia – it is surprising to find the area defended by an international literary giant. Mark Twain declared that: “Dollis Hill comes nearer to being a paradise than any other home I ever occupied.”

Praised as “the Lincoln of our literature”, “Mark Twain” (1835-1910) was the pseudonym of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. He was born in Missouri, USA and raised on the banks of the Mississippi where, as a young man, he spent four years as a river boat pilot – “the most carefree years of my life”.

In 1861, the Civil War brought an abrupt end to river traffic and Twain joined the Confederate militia as a second lieutenant, (“we didn’t have a first lieutenant”). He was a lukewarm supporter of the Southern cause and later blamed the war on the Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott. Scott, he claimed, had done so much to create the image of the Southern white aristocrat that he was to a great extent responsible for the chivalric bone-headedness that perpetuated the conflict.

Twain’s military career was short-lived. “I was a soldier two weeks and was hunted like a rat the whole time.” After a fortnight of rain and boredom, his unit disbanded. “I learned more about retreating than the man who invented retreating. There was but one honourable course for me to pursue and I pursued it. I withdrew to private life and gave the Union cause a chance.”

He spent the rest of the war mostly in Nevada dabbling in mining and journalism and concentrating on drinking.

His lifestyle changed after he was commissioned to write articles about foreign travel. He started with a successful account of life in Hawaii, then followed it with a superb travelogue The Innocents Abroad about a tour of Europe and the Middle East in 1867. The trip took five months during which he observed his fellow tourists (“a funeral excursion without the corpse”) and experienced such areas as France, Italy, and the Holy Land. When his party was charged an exorbitant price after they had hired a boat to sail on the Sea of Galilee, Twain commented: “Well, now do you wonder that Christ walked?”

The book sold 100,000 copies, began his career as a public speaker, and turned Twain into “the People’s Author”. It also gave him the financial security to start a family. Having married Olivia Langdon in 1870, he settled in Connecticut and raised three daughters.

Between 1876 and 1884 Twain published the books that were to seal his success as a great American writer – The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

The only opposition came from the Boston area where Huck Finn was banned by the Concord library. Louisa May Alcott wrote: “If Mr Twain cannot think of something better to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses he had best stop writing for them.”

Twain said he was delighted because this embargo would increase sales by at least 30,000 copies.

He performed lucrative lecture tours and became a particular favourite in England where he met his most avid fan, Charles Darwin. Twain was equally impressed by Britain, an Anglophilia aided in part by his increasing disillusion with his native country.

Twain, in company with Walt Whitman, felt that true American democracy had died in the Civil War and had been replaced by a cynical plutocracy and self-interested political leadership: “My kind of loyalty is loyalty to one’s country, not to its officeholders.” For the rest of his life, increasingly he became the scourge of capitalist profiteering and warmongering. He saw the unions as the only possible resistance: “In the unions is the working man’s only present hope of standing up like a man against money and the power of it.”

However, soon it was Twain himself who needed financial salvation. He indulged his fascination with new inventions by investing money in a series of disastrous ideas. He said later that almost the only impoverished inventor that he did not back was a young man called Alexander Graham Bell who asked him to support his new-fangled machine called a “telephone”. Twain explained: “I declined. I said I didn’t want anything more to do with wildcat speculation.”

Politically he moved increasingly to the left, declaring that he had started as a Danton but was veering towards a Marat. He spoke out against Imperialism generally and in particular the US subjugation of the Philippines and the ensuing massacres.

He continued to write and managed to restore most of his wealth, while scorning the more puritanical restrictions of old age. “The only way to keep your health,” he said, “is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d rather not”.

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. www.wildetheatre.co.uk – available at Daunts, South End Green.