There’s something about Mary

On the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s extraordinary novel Frankenstein, Nicholas Jacobs suggests its genius lies in its philosophical depth

Friday, 16th March 2018 — By Nicholas Jacobs

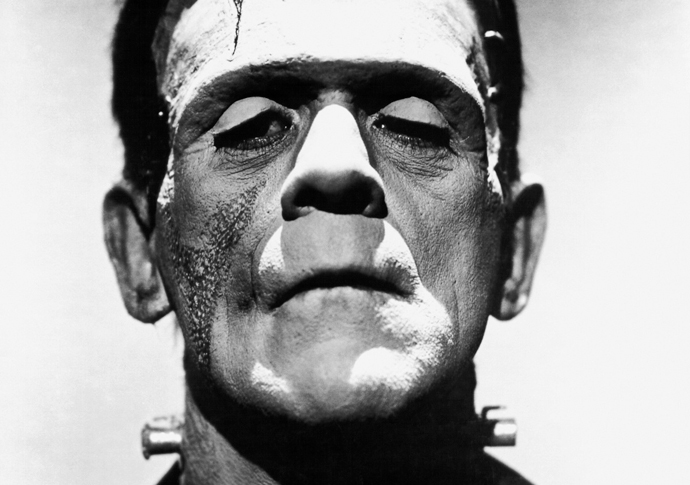

Boris Karloff: Hollywood’s vision of the creature

MARY Shelley’s Frankenstein is not only an exotic horror story like Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It is a novel of ideas, or a philosophical novel, and one of the greatest in the language.

The fact that it is also a beautifully told and frightening horror story can obscure its philosophic depth and status.

It concerns the folly and ignorance of a diligent and ambitious scientist (Victor Frankenstein), who creates a creature out of the scraps of human remains, which is therefore a monster and not only the physical victim of his creator. The nameless monster suffers social, psychological and biological deprivation.

When he quite reasonably – and for more than reason – asks for a mate, the hapless Frankenstein begins to create one, then reflects that a pair of monsters would only engender more monsters.

In thinking like this, Frankenstein, the parodic scientist, reveals his total ignorance of normal psychological and social human development and behaviour.

His creation of the monster out of the same ignorance brought him and his family nothing but misery, including the death of his best friend Cherval, and of Elisabeth, his soulmate and wife-to-be.

Frankenstein learns nothing from all this. However, the more oblivious he remains, the more the reader learns.

Frankenstein is a work of great genius by a woman not yet 20 years old. It deserves its place alongside another work of genius by a young woman, which also concerns the making of a monster through social and psychological deprivation – Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.