‘There are many plaques in Hampstead – but many more could be added'

Dan Carrier talks to John Walde, whose passion for Hampstead has culminated in a dictionary of artists who shared his love of NW3

Thursday, 16th January 2025 — By Dan Carrier

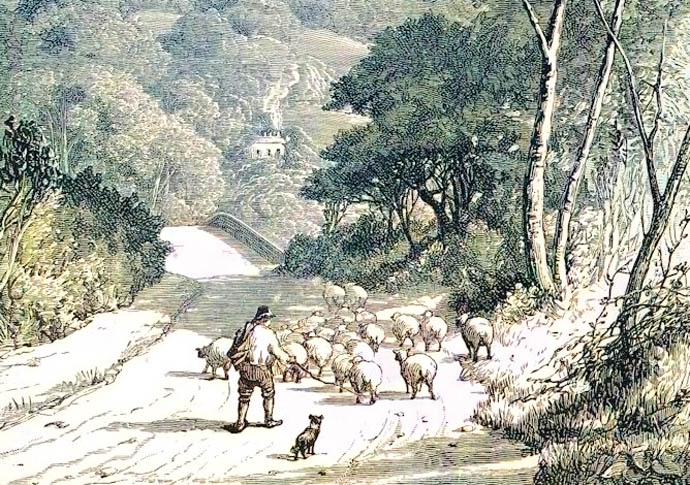

Hampstead, From the Kilburn Road. From Old and New London, edited by Walford, 1878

THE visionary carpenter’s name is lost – but we know of their work because of a print made by the artist Wenceslaus Hollar.

Hollar, who moved to England from Prague in 1637, created vistas of London.

In 1653, Hollar made his way up the slopes of Hampstead to where Jack Straw’s Castle sits today. He took out his engraving tools and settled down to record what he saw.

Hollar’s visit aimed to capture the Hollow Elm – a huge tree that persons unknown had cut a door into, scooped out the trunk and fitted a spiral staircase.

It was known for its extraordinary size: a 28ft diameter allowed for a staircase of 42 steps. Visitors would climb up to an octagonal viewing platform in the canopy to enjoy grandstand views across 17th century London.

Hollar was treading an already well-worn path to NW3 – and as a new book by historian John Walde reveals, Hampstead’s reputation for art is based on the fact that for centuries, hundreds of artistically minded people have made it their home.

Hampstead, A Nest of Gentle Artists – quoting critic Herbert Read – is a reference dictionary that lists biographies of the people who have created art from the environs.

As John explains, the village provided sketching opportunities for artists who could walk or ride from the city to the countryside.

It was not just the painters who could find rural topics on London’s doorstep. The range includes engravers like Hollar, sculptors, carvers, printmakers, potters, tilers and architects.

The book stemmed from a year’s sabbatical John spent in the 1970s in London. He had travelled from Australia and spent 12 months walking the streets of the area, discovering the wealth of stories behind his front door.

John’s partner Syd was a cabin crew member for Qantas and was offered a post in London for a year. It would kickstart a life-long project, now finally completed.

The couple were friends with renowned Australian pianist Geoffrey Parsons. He knew London well, and suggested the couple find a place in Hampstead.

“We found an enormous top-floor apartment at 37 Compayne Gardens, NW6,” he recalls. “It was the beginning of a very creative year.”

Syd had a hobby of collecting autographs, and it lead to the couple befriending the poet Stephen Spender. He would visit for drinks, among a swirl of other artistic and literary types they befriended.

One such person was Sir Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the bouncing bombs that the Dambusters used. They wrote him a letter.

John Walde

“It was answered by Lady Wallis, who wrote that she was born at 37 Compayne Gardens, and would love to visit us,” says John. “She came for afternoon tea and invited us to meet Sir Barnes at their home in Effingham. That was another fascinating day in the presence of a great man.

“Our friend and mentor, the historian Dr AL Rowse, often said you need strong legs and comfortable shoes if you want to get to know an area properly,” he adds.

“Only by walking along the streets and narrow lanes did I discover the character of Hampstead.

“I often came across a plaque on a house informing me of its history and its famous former resident, and I started making notes on each. There are many such plaques in Hampstead but as this book reveals, many more could be added.”

John was born and raised in Sweden. He worked in TV news, before a job opportunity with Australian broadcaster Channel 7 saw him head to the southern hemisphere.

“My interest in art started as a child, when I visited cathedrals, churches and art galleries.”

After retiring in 2000, John went back to the journal, in which he had made notes of the artists’ homes he had strolled past.

“I recommenced my research,” he says. “My intention was a short dictionary.”

But the project took on a life of its own. He pored over documents – births, marriages, deaths, probates and referenced the British Newspaper Archives.

“I visited London seven times, visiting the local archives and in the Royal Academy’s library,” he says.

Packed with stories, the dictionary has all the names you’d expect – Moore, Hepworth, Constable.

But John’s research offers a remarkable gateway to a swathe of people whose talents have brightened the world but are virtually unknown. It conjures up a pre-digital age when hand-crafted art was the only way to work.

Hidden in the entries are triumphs and tragedies: for example, Mary Oliver, born 1892 in Kentish Town, focused on portraits, landscapes of Italy and Greece and still life. She was a graduate of the Slade and moved to Downshire Hill in 1925. On September 13, 1940 she walked the short distance to her friend Carl Hempel’s home in Adelaide Road. A bomb hit the house, killing 11 people inside – including Mary.

Another entry casts light on the life of tile-maker William De Morgan, who lived in Hampstead until his death in 1917.

His mother Sophie was a radical political campaigner, his father a maths professor, who inspired the geometric patterns and symmetry on his ceramics. A student at the Royal Academy of Arts, he met William Morris. The Arts and Crafts originator would become a key influence, inspiring a move into stained glass and furniture.

Glass required learning technical methods – and De Morgan’s curiosity saw him determined to improve them.

An inventor, he came across a long-forgotten system of making ceramics with a metallic glaze. The ancient technique, known as lustreware, was produced up to the Renaissance, but had disappeared. William set his heart on rediscovering the technique and it would earn him high-end commissions, ranging from Lord Leighton’s “Arab Hall” extension of his Holland Park home to the Czar of Russia’s yacht-building team.

His last commission was to create a monument in the City of London’s Postman’s Park. It celebrates people who have given their lives in acts of heroism and he listed the names and acts committed.

Later, as John’s excellent research reveals, William turned his hand to writing fiction – and penned seven bestsellers.

• Hampstead: A Nest of Gentle Artists. By John Walde, ETT IMPRINT, £65