There are complex stories concerning the Benin bronzes

Friday, 7th May 2021

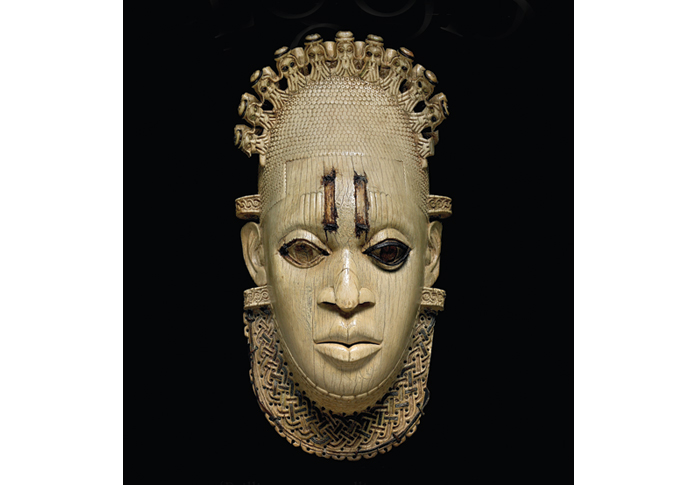

Queen Idia Ivory Mask, perhaps the greatest of all Benin’s treasures, is now in the British Museum

• FURTHER to Dan Carrier’s review of Barnaby Phillips’s book ‘Loot, Britain and the Benin Bronzes‘ (Alloy steal, April 29), in 1978 I saw Nigeria from end to end, having been offered a rare visa to photograph the results of the oil boom.

The Biafran War was a recent memory so there was paranoia about a white man with cameras, and my minder often had to explain me to soldiers and police, flourishing his letter from the ministry.

The Guardian and other papers and magazines used the photos for years, no other photographer having got in; the portrait of Fela Kuti at home in Lagos with most of his 27 wives has been printed countless times.

In Benin we found a few artisans using lost-wax to cast some awful pieces – the old craftsmanship was gone.

So I asked to see what was in the museum there. This was unwelcome but I did get in eventually.

When I asked the curator why there were all these gaps on the shelves and cabinets, he explained that government ministers were in the habit of sending to the museum when they wanted a gift for a foreign dignitary.

Sad as this was, people were being shot at road blocks, lynched after traffic accidents, and when the military machine-gunned prisoners lashed to oil barrels on Bar Beach, NTV broadcast the spectacle.

Life was precarious and I could understand the museum staff not arguing with men carrying guns. I certainly wasn’t going to put them in further danger by photographing the gaps on their shelves.

In 2016 Prince Akenzua in Benin demanded the return of Jesus College’s bronze cockerel and reporter Colin Freeman went there to interview him (Sunday Telegraph, October 9 2016).

Unfortunately he found the Benin museum “currently closed for refurbishment” and couldn’t get inside. I wonder what he’d have found, or rather found missing, if he had?

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Colonial Office bought Nigerian bronzes on the international art market, and at independence in 1960 were able to leave the new nation with well-stocked museums in Lagos and Benin.

So any museum thinking of restituting bronzes should first be asking the Nigerian government to declare their holdings in 1960 and prove where those pieces are today.

One such masterpiece is now in Windsor Castle. General Yakubu Gowon’s gift on his state visit in 1973 purported to be a modern copy of a 12-inch bronze Oba’s head dating from c1600.

In fact the replica he’d commissioned was so hopeless that he just stole the original from Lagos museum and presented that to the Queen.

These days 3D replicas are indistinguishable and until Nigeria finds and repatriates bronzes which Nigerians themselves have looted since 1960, replicas are what the world’s museums should send back.

MIKE WELLS

Balmore Street, N19