The living image

Mike Abrahams’ photographs of 1970s Kentish Town capture a bygone world. Now a fellow photographer has revisited the same scenes to record what’s changed. Dan Carrier talked to both of them

Thursday, 25th July 2024 — By Dan Carrier

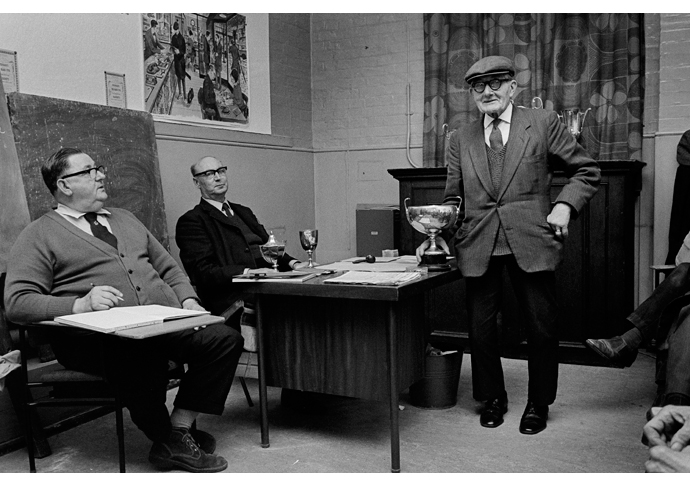

Mike Abrahams’ photographs of Kentish Town in 1975: Street life [Mike Abrahams]

MIKE Abrahams has shot some iconic photographs. His work took him to Northern Ireland, to Assad’s Syria, to watch the Velvet Revolution in Prague, and post-Ceaușescu Romania.

His work may be global but in his archive, West Hampstead-based Mike has a fascinating 1975 study of people in Kentish Town.

Now, 50 years after the project was published, another photographer, Attila Bela Babos, has identified the places Mike took shots and reproduced them today for a yet-to-be-published book.

Originally from Vienna, Attila came to London 25 years ago for a holiday and never left.

“I went to gigs in Camden Town and I decided I was staying. My mum was bemused when I didn’t return, but I was massively into Brit Pop and felt I had found my place.”

He began work in a Camden Lock shop to pay his way. “Photography is my main passion,” he explains. “I work commercially, and do personal projects.

“I love collecting old photographs and I am always searching for images. I found Mike’s work and it was brilliant.

“I researched places and started shooting the people and places that I found interesting.”

Anyone who claims NW5 roots can recognise Mike’s images.

“Some parts have changed so much, but you could still find where he stood. It shows the scale of change.

“Mike’s work is natural, observational, artistic. He has the ability to capture someone, just at the right moment, and reveal who they are.”

Pigeon fanciers bringing their birds to the drop-off point to be picked up and delivered to the start in Holmes Road

The Kentish Town work was at the start of a fruitful career for Mike. The Liverpool-born photographer arrived in London in the early 1970s to study at the Central London Polytechnic, and this was his final year project.

“I lived around Grafton Road,” he recalls. “I used to use the baths there – 8p a swim and you could stay all day.”

It is no surprise that he photographed a collection of women at the entrance to the bath’s laundry rooms.

It was an early example of the humanist and natural photography that he became known for, and led to him capturing the social conscience he felt.

Mike worked with a community newspaper and the Writers and Readers Publishing Group, based at Talacre.

“I was given a grant by Kodak and I started making slideshows with tenants campaigning on housing,” he says.

“We interviewed people, took photographs of the conditions they lived in, went to tenants meetings.”

Mike recalls how he first caught the photography bug.

“I was 12 and a friend had a rudimentary dark room under the stairs,” he recalls. “We printed a picture and I thought: majestic.”

He was given a basic developing kit for his bar mitzvah and aged 15, his first secondhand camera.

“I went out wandering around Liverpool, taking photographs. Totexth was rough. You could not tell what was bomb damage and what was just decay and desolation. There was a lot of slum housing. I would go into people’s homes to take images and they were wonderful, full of support – but their situations were crap. It was real deprivation.”

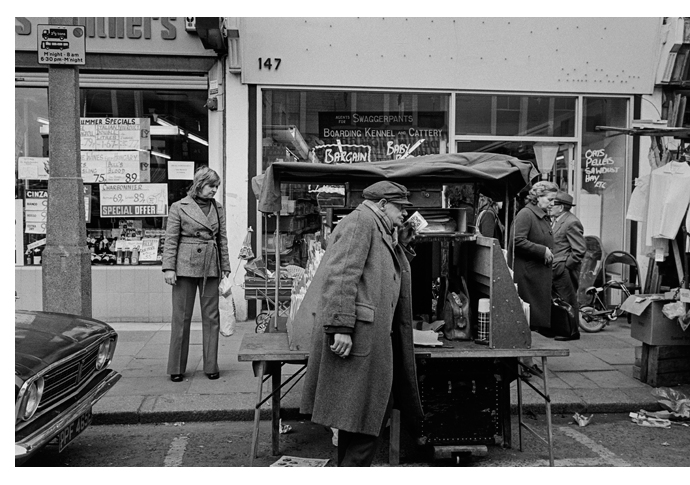

Queen’s Crescent market

It led to an exhibition and a portfolio. “For a lad from Liverpool, it was inconceivable to be a photographer in the manner I wanted to be. I could do weddings and bar mitzvahs, but that wasn’t me.”

He reels off influences and names Larry Burrows, who worked for Life magazine. London-born, Burrows went to Vietnam between 1960 and 1971 and was killed when a helicopter carrying him was shot down.

Mike was struck by Burrows’ work. “His Vietnam images were incredible and set me zinging,” he says.

Another photographer who went to Vietnam and China stood out.

“I loved Marc Riboud, the French humanist photographer. He took images that were not war pictures. I realised you can capture very human pictures about life in conflicts without actually shooting the conflicts. That made me think about how we photograph daily life. They were like poetry to me.”

His career has spanned massive technological changes and shooting on film is a very different experience to digital, he says.

“Analogue was a more deliberate process,” he said. “I might shoot 100 rolls of film on an assignment. I had to then process it, print it. It means you have a very intensive relationship with the image. You have to take out the film, make sure there is an image on there, make contact sheets, look at them through a magnifying glass.

“You would print your selected images and then you had a physical object you could hold. There was this process of editing until you had the shot you wanted.”

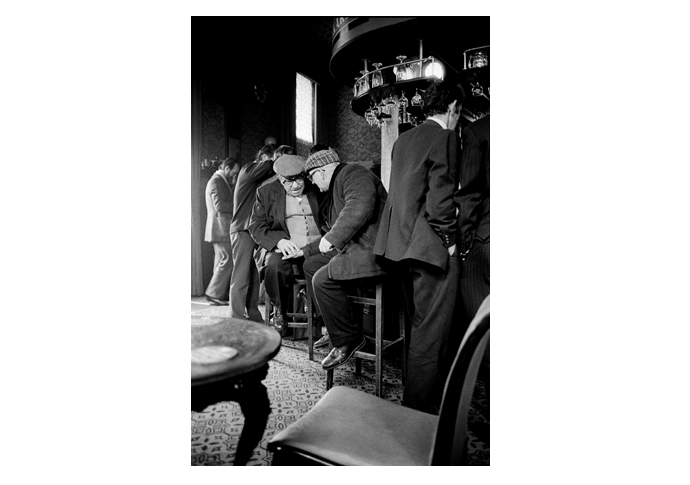

Two elderly men in cloth caps chat over a pint in The Mamelon Tower pub on the corner of Grafton Road and Queen’s Crescent

In the early 1980s, Mike teamed up with others to establish the Network Photographers agency, which was based in Kentish Town Road. It had a global reach.

“We were a bunch of like-minded photographers interested in social issues, and we knew each other from the streets,” he recalls.

The agency earned commissions that took Mike abroad.

“I was in Berlin for six months before the wall came down,” he remembers.

“I did a series along the length of the wall – it was weird. I saw cranes lifting a section of the wall away and East German guards coming through. I thought: ‘Hello, something big is happening here. Maybe it is an invasion. What a scoop.’ They came up to me and said: ‘No pictures!’ I said: “Sorry, you have no jurisdiction, I am in the West.’ I pointed to the ground where there were a series of brass markers on the floor and said: ‘That’s the boundary, you’re on the wrong side.’”

He won awards for his work in Northern Ireland.

“I was interested in daily life,” he says.

“In the British press, people were seen as living in neighbourhoods who support the IRA. I wanted to know who they were. I wanted to capture life in these communities. I was not interested in people throwing stones.”

Attila Bela Babos

And he saw how life goes on as political violence raged.

“What made life tick was the same for anyone anywhere else, whether it be Belfast, Glasgow or Kentish Town. People have the same needs, their lives are recognisable – and they have the same sense of powerlessness and dislocation. Yet what they faced was extraordinary. I spent a lot of time in Ardoyne. It is a place of 11,000 people and 99 had died at the hands of the Loyalist Paramilitaries, the RUC and the British Army. It showed how much life was affected.”

Being in the right place and right time for an image is a trick only the best know.

“I am shy and it suits me to stay in the background,” he says about how he captures his work.

“I never want to be part of the story. I start by explaining who I am and why. Quite often it is about making eye contact that says: are you okay with this?

“You can pick up quickly about people not being fine. Consent is important. If I want to photograph you, I want you to be okay with that.”

But above all it is winning trust.

“I remember walking down a Northern Irish street and people were suspicious. But you find one person who is okay with you, and then others feel they are, too,” he adds.

“Access is everything. I don’t sneak about but I use small cameras. I don’t want to be confronting people with something that looks like a weapon. Then it is a question of watching and waiting for that special moment when everything comes into place.”