The left-right battle in the Labour Party has history

Friday, 30th July 2021

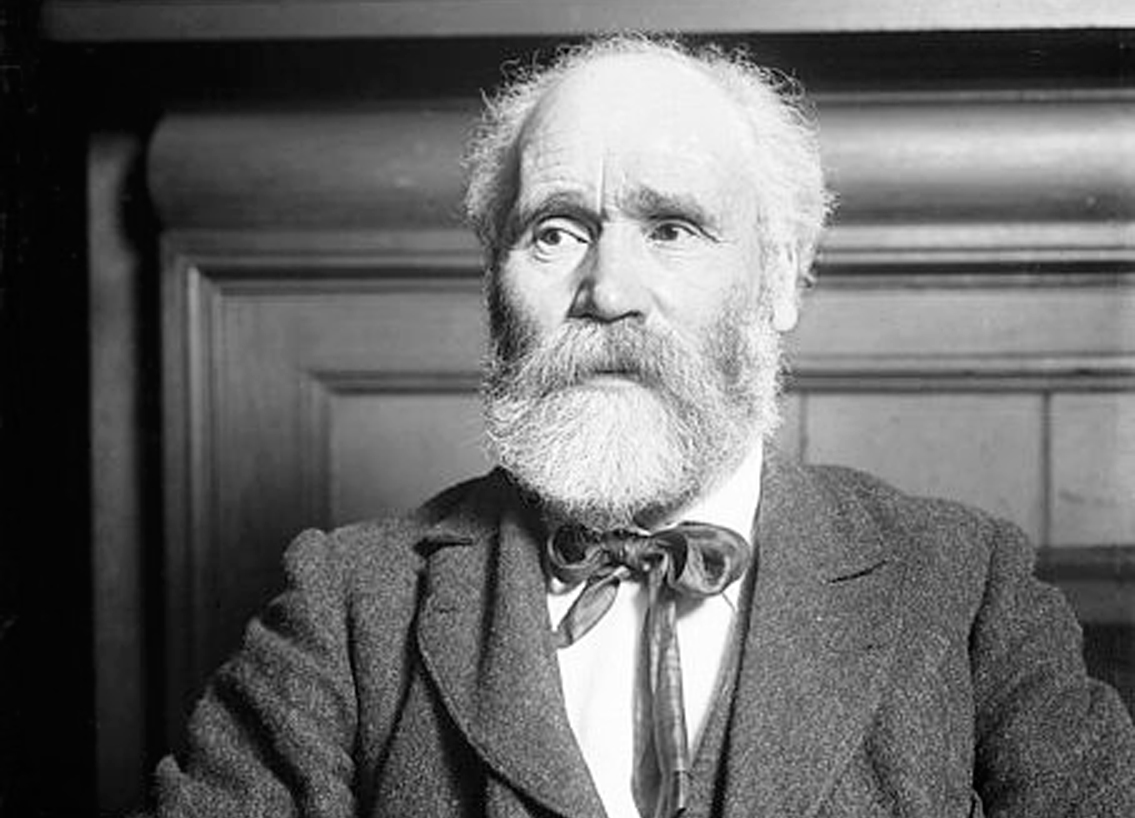

Keir Hardie. Picture: Wiki Commons

• PHIL Vasili reminded your readers of my 2020 comment that Sir Keir Starmer’s “socialism runs deep. He is a man steeped in the socialist tradition that springs from the earliest days of the Labour Party”, (Socialism and Sir Keir, July 22).

He questioned this assertion on the grounds that Sir Keir was prepared to expel Labour Party members whom Vasili describes as “socialists.”

The question of what kind of socialism Labour should follow goes back to the very origins of the party.

The founding of the Labour Party at a conference in February 1900 was the culmination of years of negotiations.

The meeting in Farringdon Street brought together Keir Hardie’s Independent Labour Party, the Trades Union Congress, the Fabian Society and delegates of the Marxist Social Democratic Federation.

Hardie was anything but an ideologue. Born in dire poverty, and having spent his early years down the mines, he wanted to improve the lot of the working class.

As he later said: “the object of the conference was not to discuss first principles but to endeavour to ascertain whether organisation representing different ideals could find an immediate and practical common ground”.

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) led by Henry Hyndman, son of a wealthy businessman with plantations in Barbados, was rather different.

A Marxist, he believed in the creative power of destruction. “I despair of a peaceful solution to the inevitable class struggle even in England” he wrote, “and I fear that we must pass through the fiery furnace of ‘some fatal natural catastrophe’ to the goal of full economic freedom and organised work for all.”

This view came from a belief that electing members of parliament was really only a step on the road to revolution.

The SDF proposed: “representatives of the working class movement in the House of Commons shall form there a distinct party based on the recognition of the class war and having for its ultimate object the socialisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange”.

Hardie opposed this with a resolution “in favour of establishing a distinct Labour group in Parliament who shall have their own whips and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to co-operate with any party which, for the time being, may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interest of labour”.

Hardie won the debate by 53 votes to 39.

The SDF were only members of the Labour Representation Committee, as it was then called, for a short period. The SDF had little control over policy and gradually broke away.

Yet soon they regretted the split. “We have to capture rather than oppose it,” declared a London SDF member.

This is exactly what the hard-left have been attempting to do ever since. It is the strategy of “entryism.”

In the 1980s this took the form of the Militant Tendency. In recent years they have organised around and controlled Momentum (which drew support from a much wider range of people).

Far left groups have always ruthlessly expelled members who deviated from their ideologies. Yet they have complained vociferously when the Labour Party tries to root them out of its own ranks.

Given Labour’s history, and the far-left’s determination to “capture it”, this is not a battle the Labour can duck as it reaches out to win the support of the British public.

MARTIN PLAUT, NW5