The goods life

How the Age of Steam informed our neck of the woods is the subject of a new book. Dan Carrier keeps track of events

Thursday, 19th September 2024 — By Dan Carrier

View from bridge to Camden Shed in 1938

SPARE a thought for the nightwatch-man on the London-to-Birmingham line. The job meant being stationed at the Chalk Farm goods depots and keeping a sharp eye.

With thousands of pounds of goods stored in bonded sheds, it offered tempting rich pickings to the desperate.

But it wasn’t just light-fingered locals the nightwatchman was looking out for. Livestock were a vital part of the freight brought in on the new line and included cattle landings at Camden Town.

A new book by historian Peter Darley outlines the incredible story of Camden’s railways – and describes how a part of our neighbourhood was built and the impact it had.

He explains how the London-to-Birmingham railway line was built and came into Camden Town, bringing with it a new world of freight.

“The animals in their excitement often escaped onto the main line, charging the trains,” he quotes a contemporary report from 1839 as saying.

And it wasn’t just cows the unfortunate nightwatchman had to worry about: “A sharp watchman, in a dimly lit goods shed at Camden, once found a bear that had escaped from Euston, crouching against a wagon, and taking it for a thief, he pounced upon it, but retreated in dismay, unhurt.”

Peter is the founder of the Camden Town Railway Heritage Society and has surveyed and researched the infrastructure around us that has been in place long enough to feel as old the hills.

His journey began in 2005. He had recently stepped back from full-time work and instead was enjoying freelance jobs and taking the time to explore a neighbourhood he had lived in for may years but had always been too busy to fully get to know. “I live very close to the Primrose Hill portal. I came across and immediately thought: why is the finest structure in the area so hidden and so little known?”

Peter Darley in the wine and beer vaults

Peter’s career as a surveyor and engineer took him to Aberdeen and the North Sea oil industry after graduating. From there, he turned to civil engineering, working in agricultural infrastructure.

Then came a planning battle in 2007, regarding the future of a canalside warehouse once used by Muppets creator Jim Henson. It led to the heritage trust forming with the aim of documenting the industrial history and opening it up. Peter has created a complete study of the history of the railways in Camden Town and is the basis of the new book.

It begins in 1830 with the formation of the London and Birmingham Railway Company: 20 years earlier, transport was waterborne. The Regent’s Canal had opened and goods were making stately journeys along it.

But the Age of Steam was rapidly catching up. The Stockton-to-Darlington railway had opened, and tracks were being laid across the country – and London and the UK’s second city required a link.

George Stephenson and son were appointed as civil engineers and Peter walks the reader through the options they considered, the surveys they did and the painful obstacles they needed to overcome – often financial and legal as well as in the construction.

It was a big job, with muscle power being as important as steam. Up to 12,000 men were employed to build the L&BR at its peak and it was dark, dirty and incredibly dangerous.

“Yet navvies could be highly disciplined and relished the challenge of hard and difficult work. Drunk or sober, the work was dangerous and injuries and fatalities were accepted as inevitable. Every mile of the L&BR cost an average of three lives, with a far higher toll when it came to tunnels and cuttings.”

The stretch of line that first caught Peter’s attention was notorious.

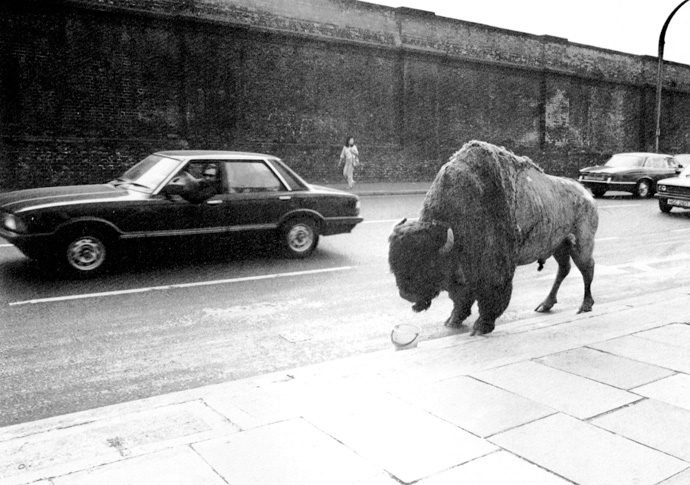

Great Wall of Camden from ‘Bison at Chalk Farm’, 1982

“The treacherous nature of the land around Primrose Hill saw the tunnel there lead to many deaths – and the Chalk Farm Tavern was where the bodies of unfortunate navvies would be taken,” he adds. “One tunnel collapse saw 30 men buried. It took 21 days to recover the final body.”

The railways brought along with them a raft of new technologies.

Passenger trains were not, at first, going to be welcomed into Euston station with a steam-producing engine at the helm. Instead, a winding house was built that would take the carriages down the slope to the new station and up again, without covering the well-heeled land owner’s homes in soot. This in itself was a sign of their problem-solving approach.

The issue of how operators at both ends of the line could talk to each other was approached by inventors Fothergill Cooke and Professor Wheatstone. They hit upon an idea that was a rudimentary intercom system.

“The device had been patented the previous month and on June 25, 1837 Professor Wheatstone sat in a small room in Euston station and Robert Stephenson and Fothergill Cooke sat in Camden Town.

“Two copper wires were laid between Euston and Camden and the two quiet inventors placed themselves at either end and conversed.”

Peter’s work reveals everything from the fact they used hemp ropes imported from Russia to pull the locomotives to the vital economic role of horses – and how they were cared for. Alongside the goods yards, stabling was crucial and across Camden Lock and the markets are the signs of their original purpose, which Peter has diligently logged. And the decline of horsepower is a recent scandal: as recently as 1948, 200,000 horses in London were put down – 40 per cent of them under three years old.

The story of drinks firm Gilbeys, which employed many Camden Town workers, is told: “Created in 1857 as an importer of inexpensive wine, it established warehouses and businesses in the West End,” Peter reveals.

They soon outgrew their central HQ and struck a deal to take on the Roundhouse and the Pickfords shed. They would stay in the area for the next 100 years. Business was such that Gilbeys stored four million litres of alcoholic drinks on site – and their international reputation saw thousands of gallons of their gin smuggled into Prohibition America. It gave them a leading market share when the booze ban was finally lifted.

Peter’s history has the level of detailed research an academic or researcher would require, combined with the human stories that make his work both informative, accessible and entertaining. A fulsome history of a world hidden by the passing years, right on our doorstep.

• Chalk Farm Railway Lands: A Guided Tour 1830 to 2030. By Peter Darley, Grosvenor House Publishing, £25