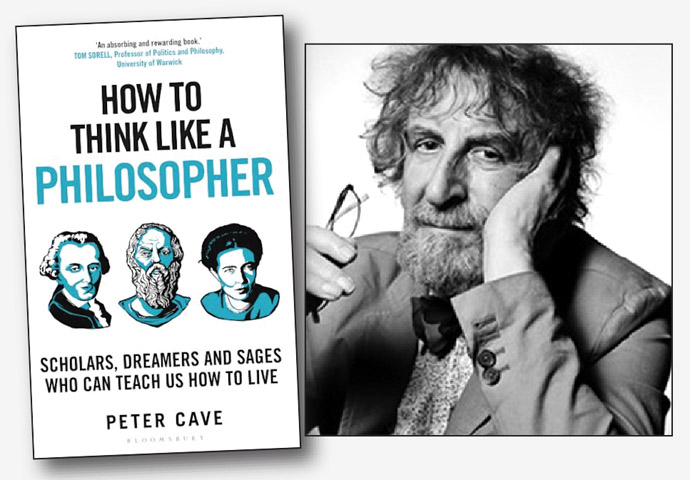

How to think like a philosopher

Peter Cave notes that many of the philosophers featured in his new book trod the streets of north London

Friday, 5th May 2023 — By Peter Cave

Above: John Stuart Mill; right: Bertrand Russell

Peter Cave [Richard Piercy Photographer]

‘Tis better to be a dissatisfied Socrates than a satisfied pig.

The mantra above is from the great Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill, born 1806 in Pentonville, and much associated with Jeremy Bentham, his atheist “godfather”.

Bentham’s “spirit”, bones and writings rest within the secular Bloomsbury 1826 foundations of London University, as it was originally conceived. In my day, it had become University College or UC; now it is UCL.

Mill’s mantra should make us wonder how to live. Bertrand Russell – Mill was his secular “godfather” – is also within Bloomsbury; his bust, rewaxed, is in Red Lion Square. Russell quipped: “Most people would rather die than think; and that is what they do.”

Some of us recall his Trafalgar Square CND sit-downs decades ago and his imprisonments.

Without thinking much at all, many maintain that pleasure is all that matters. That answer needs rejection. Using that greatest of philosophers, Plato, I note that if pleasure alone is all that matters – well, buy itching powder, sprinkle, itch, scratch, delighting in satisfying pleasures; repeat, repeat…

Philosophy encourages thinking, good reasoning; it also draws attention to values, our humanity and even the need for humility. However impressive the reasoning, it counts for nothing if ignoring the plight of the poor. It counts for little, if glorifying freedom, yet has eyes closed to what is needed to exercise freedom. If you lack the money, there’s no freedom to take trips, attend events – be they football, cricket or the wonderful Wigmore Hall and English National Opera – or even bake Coronation Quiche.

Iris Murdoch; Arthur Schopenhauer

Further, the freedom granted to corporations often leads to… Well, to media misinformation, promotion of addictions such as gambling and to properties left empty, owned by offshore trusts with hidden beneficiaries. So much for Britain as a well-informed democracy and defender of people’s dignity.

Living in Soho, I am easily stimulated by such philosophical thinking and philosophers’ lives. Naturally, then, I accepted the commission from, appropriately located, Bloomsbury Publishing to write on 30 philosophers: How To Think Like a Philosopher: Scholars, Dreamers and Sages Who Can Teach Us How to Live.

Round the corner, there’s Karl Marx. More accurately, there’s the blue plaque much gazed upon by tourists; it now incongruously labels an expensive restaurant (I haven’t been there, daring not to face the bill). Of course, there’s Marx’s bust, much daubed by outraged paint, in Highgate Cemetery. In Newington Green, we have Mary Wollstonecraft and her determined promotion of women’s rights. There are also philosophers not so readily associated with this part of London.

In the 1960s, Samuel Beckett – yes, I deem him “philosopher” – was crossing Regent’s Park, off to Lord’s Cricket. He noted the beautiful blue sky, the greens of the trees, the company of friends. One remarked: “Yes, on a day like this, it’s good to be alive.”

Beckett’s reply: “Well, I wouldn’t go as far as that.”

Ever present in Beckett’s works is awareness of life’s sufferings, ailments and sheer boredom. He is at one with Arthur Schopenhauer, philosopher of pessimism. Both find value in losing the “self” in music. Philosophical reflections easily lead to bafflement over what a “self” even is. What we do know is that many people focus exclusively on themselves, their own well-being, disregarding that of others.

Maynard Keynes; Simone Weil

My book also offers Simone Weil, a significant thinker with a mystical Christian emphasis. She spent her last couple of years in London, trying to join de Gaulle’s Free French – associated with Soho’s “The French” – and return to Paris. Her frailty and Jewishness put an end to that ambition. Her end, in 1943, was in Middlesex Hospital, then in Fitzrovia, having virtually starved herself to death.

Simone de Beauvoir had reported how Simone Weil wanted to feed the world. When she (Beauvoir) replied that the goal was to find meaning in one’s existence, Weil replied: “It’s easy to see you’ve never gone hungry.” Human beings, Weil wrote, are so made that the ones who do the crushing feel nothing; it is the person crushed who feels what is happening. Unless we have placed ourselves on the side of the oppressed, to feel with them, we cannot understand.

That thought takes us to Iris Murdoch, also a philosopher, though known primarily as novelist. In 1950s Hampstead, she was having an affair with Elias Canetti, later to be a Nobel Prize winner.

Murdoch wrote: “When I was young I thought freedom was the thing. Later on, virtue was the thing.” She then adds how she now sees that one really must begin at the food and shelter level.

I hope that the reflections above remind us of the dire state of Britain’s current ethos. Many people accept sadly as inevitable – some even approvingly – a wealthy country such as Britain having millions in poverty, in poor housing, in poor health, with support for community and cultural uplifts ever declining.

When others stand up and challenge that ethos – Jeremy Corbyn comes to mind as a courageous example – they are disparaged, lied about, deemed antisemitic, even favouring Putin’s Russian dictatorship.

The above muses on certain political aspects to thinking philosophically; there are many other worthy aspects, displayed by my 30 philosophers from Lao Tzu to Wittgenstein, from Spinoza to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

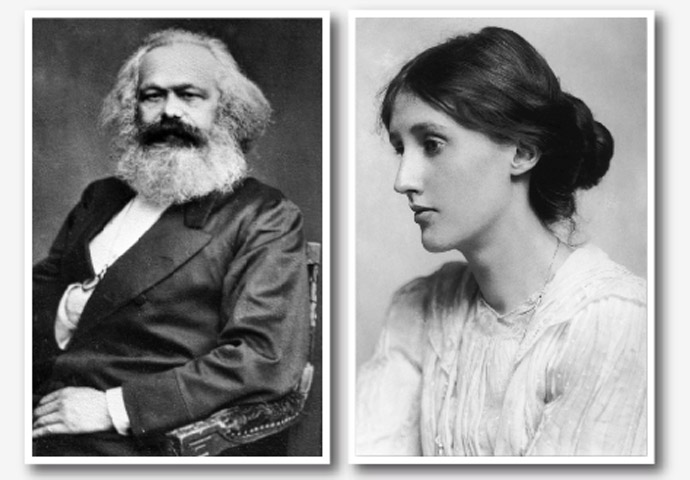

Karl Marx; Virginia Woolf [George Charles Beresford]

Returning to Bloomsbury, we meet the Bloomsbury Group, with Virginia Woolf, EM Forster and Maynard Keynes. The Cambridge professor, GE Moore, little known outside of philosophy, was the greatest influence on that group, with his purity and honesty, contrasting with Russell’s wayward ways with women. They were members of the well-known secret society, The Apostles; it occasionally dined at Kettners and the Savoy.

Both Russell and Moore had reacted against John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart – what a wonderful name – with his insistence that time was unreal. The young Moore would ask: “Are you telling me, Jack, I didn’t have my breakfast before tea?”

Moore receives the prize for bringing the sense of common sense to philosophy, demanding that philosophers’ theories should be pinned down in everyday language. In Moore’s older years, younger philosophers were critical of his silences. Was he seeing himself as a great and silent sage? Once when challenged over his silence, his reply was: “I didn’t want to be silent. I couldn’t think of anything to say.”

In today’s incessant media chatter, Moore’s comment here is a fine thought to follow. With the troubles of today’s society, though, I return to the blue plaque in Dean Street – to Karl Marx.

Using Perseus, a legendary figure of Greek myth, Marx wrote: “Perseus wore a magic cap that the monsters he hunted down might not see him. We draw the magic cap down over eyes and ears as a make-believe that there are no monsters.”

We need to take off the cap. Thinking philosophically can help – at least a little.

• How To Think Like a Philosopher: Scholars, Dreamers and Sages Who Can Teach Us How to Live. By Peter Cave. Bloomsbury, £16.99