‘Stella did not achieve the recognition or success in her lifetime her work deserves’

The name of artist Stella Magarshack should, argue her family, be more well known. And now a new book of her work aims to make that the case. Dan Carrier reports

Friday, 22nd August 2025 — By Dan Carrier

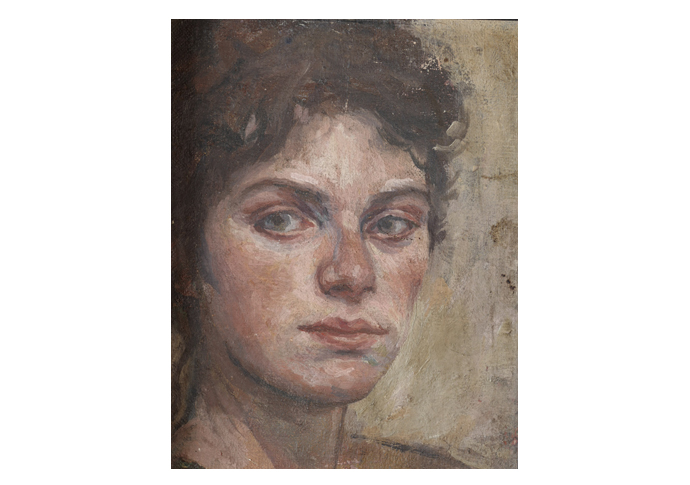

A self-portrait by Stella Magarshack

THE craft that goes into the works by Stella Magarshack shows a lifetime of determined application: but it also shows a passion and love for the art work her extraordinary talent created.

Yet her name, which could be as well known as her contemporary and friend Frank Auerbach, remains treasured by her family and the many students she taught – but does not have the public recognition lesser artists have enjoyed.

Stella died in 2019 aged 80 and now a new book, collated by her nieces and nephews who have inherited an exceptional body of art, tells her story and brings her work to the wider audience it deserves.

Nephew John Morris and niece Emily Morris had the enviable job of looking through hundreds of works – oil paintings, sketches and lino cuts – to choose a number that showed her range and subject matter.

It reveals an artist who was firmly rooted in the north London she lived and worked in throughout her life – images of Camden Town, Belsize Park, Primrose Hill and Archway.

Stella was born in 1929 and grew up in the Vale of Health, Hampstead. She was one of four children: her father David was a Jewish Latvian refugee who escaped pogroms.

Her mother Elsie was a trailblazer – she earned a place at Cambridge University in the first year they admitted female students, and while she completed her degree, she never graduated as they only allowed men to do so.

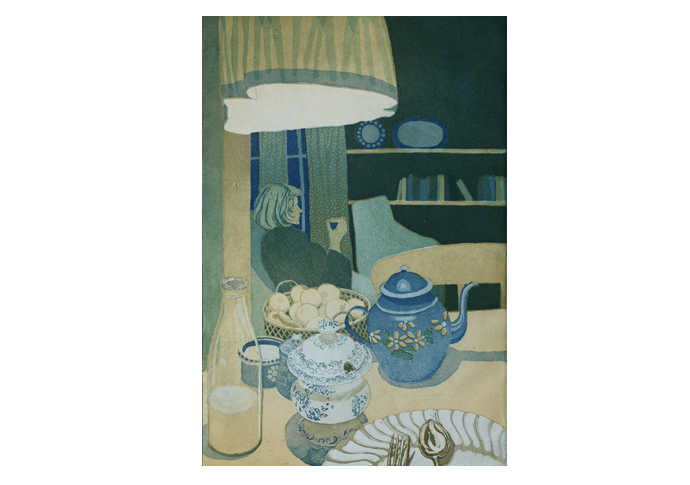

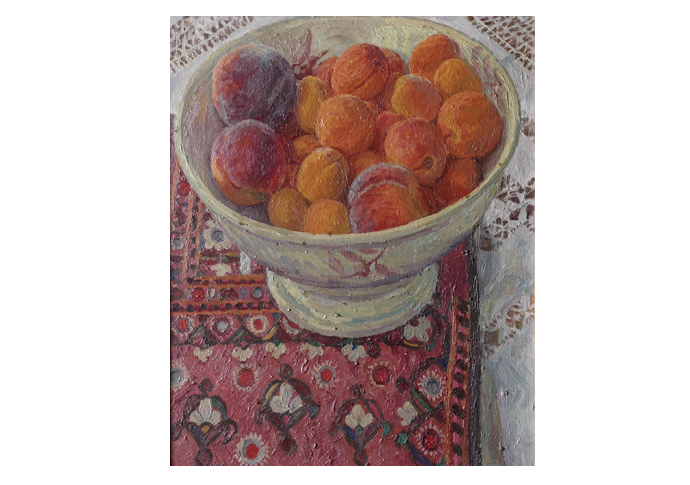

Above and below: some examples of Stella Magarshack’s work

Elsie – who features in many of Stella’s home-painted images – would become home tutor while David had designs on being a novelist. He earned a living as a journalist to help pay the family’s way, and would also be a translator of Chekhov and Dostoevsky for Penguin.

The Vale of Health at the time was also home to Cold Comfort Farm writer Stella Gibbons and the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. Her family were bohemian and mixed in Hampstead literary and artistic circles between the wars. Later her brother Chris would become a celebrated potter and establish the Well Walk Pottery.

“She grew up in a bohemian, intelligentsia environment,” reflects John. “Her mother came from a working-class background and her father was a refugee, so they weren’t part of the establishment, they weren’t posh.”

The family’s precarious income meant she moved frequently, and her childhood education was further interrupted by evacuation during the war.

This did not impact on her talent shining – she pursued a degree at Central St Martins, where she was a contemporary of the artist Frank Auerbach and would later be his neighbour in Albert Street, Camden Town. Her training continued at the Royal College of Art.

Eleven of her works were exhibited at the Royal Academy and she was offered the chance to become an Academician, an opportunity she declined.

Instead, she dedicated her life to her art work and paid her way by teaching.

She taught at secondary school in Essex for a time before she joined King Alfred’s in Hampstead in the 1960s and became their head of art, a post she held until her retirement.

Her work reflected the world she saw, adds Emily.

“Her work used the interiors of the many flats she lived in,” adds Emily.

“Wherever she stayed, she made it quite magical. She painted views from her windows – she would paint at her kitchen table, and always from still life.”

And the warmth in the imagery was a reflection of a woman whose domesticity oozed love and warmth. Her cooking was legendary among family and friends, dishes laden with garlic, butter and cream, huge Christmas feasts – while the family often feature. One etching is of John as a child, wearing a tea cosy on his head and pretending to be a Buckingham Palace guard, wearing a bearskin hat. Stella, he reflects, captured him perfectly.

“She found it a hard discipline,” adds Emily.

“As a teacher she felt that drawing from life was really important. She felt it was important to hone your craft, to paint what you saw. She believed in hard work – she never took short cuts, with her art or her cooking. She would create lino cuts that had 10 different colours in them – her process was meticulous, and she was always making something beautiful. There was always work on the go. She would occasionally paint from sketches she made but she loved to paint what was in front of her.”

Stella’s role in her family’s life was such that her nieces and nephews feel, six years after her death, her work deserved a wider audience.

“She was always quite shy – she didn’t like exhibitions,” recalls Emily.

“But she always, always painted.”

Stella loved oil and lino cuts and the book reveals examples of her craft.

“She would always have a painting on the go,” adds John.

“Stella did not achieve the recognition or success in her lifetime I believe her work deserves.

“She would have scoffed at this statement. Self-promotion requires a certain egotism or a quality of bravado that she did not have, or more importantly, did not want.”

Another nephew, Andrew, adds in the book: “All her life Stella shunned self-promotion.

“She has left us with a treasure trove of works of art, most of which were stacked up or in drawers and few people have ever seen.

“It is hoped that the selection of her works collected in this book will take her work to a wider audience, who will be able to enjoy and appreciate the vivid scenes and qualities that her art conveys.”

• Stella Magarshack. By John and Emily Morris. £30. Available at The Owl, Kentish Town and Daunt books outlets, or direct from info@kingscrosseyes