Review: Reel Life Behind The Screen: A Memoir, by Nick Scudamore

A new memoir shines a light on what it’s like to be a cinema manager, says Dan Carrier

Thursday, 12th January 2023 — By Dan Carrier

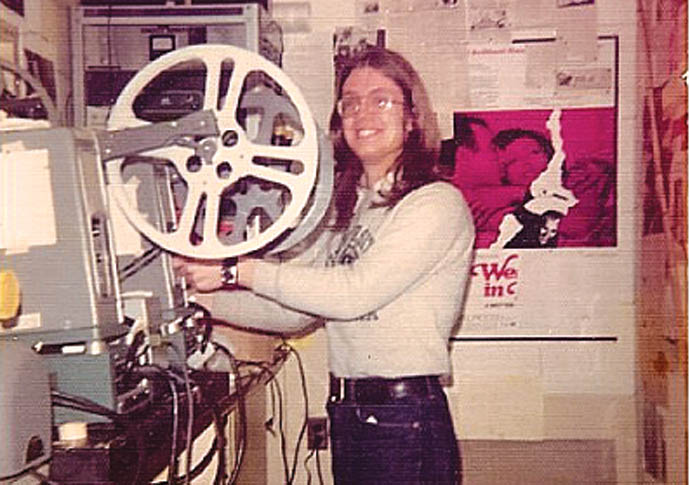

Nick Scudamore in the 1970s in the projection booth at the University of Virginia where he was a member of the Film Society

THERE was, says Nick Scudamore, a “sense of local commitment”.

It was the summer of 1980 and Nick had been given a job at the famous Islington art house cinema, the Screen on the Green.

“The depth and range of the regulars was exceptional,” he writes in a memoir that covers four decades as a north London cinema manager.

“There were old-school film buffs, all dandruff and thermos flasks. There were bespiked Goths along with various sub sets of intellectual punks. There were art school dandies in their gloriously retro-fitted oversize overcoats and hand-painted pixie boots. There were slightly battered skinhead and suedehead couples, both in matching braces and boots, him with fewer teeth than her. There were assistant editors of Granta in well-rubbed biker jackets.”

In Reel Life Behind The Screen, Nick turns the daily routine of running a cinema into a consideration of selling your labour for a wage, backlit by the never-ending curiousness of fellow humans, and a cultural history of a medium that shaped the 20th century.

Nick had worked in the family’s bookshop in Earl’s Court after graduating. It was a holding role until he decided what he’d like to do. He had always been fascinated by film – as a teenager he kept a card record of every film he had ever seen, storing cards in alphabetical order, complete with criticism.

“My father liked to take me to the pictures as a weekly outing,” he recalls. “The picture was huge and often in colour, the narrative always clear and compelling.”

When the bookshop closed following his father’s retirement, Nick needed a new job. He became involved in a community newsletter called Response, and was given free passes to the Paris Pullman art house cinema, in return for a review.

“I was a notorious film buff (read film bore) even then,” he writes. Nick took on reviewing, joining critics in screening rooms in the West End. Dropping off his reviews to the Paris Pullman, he befriended the manager and was eventually asked to become the assistant manager with a focus on organising late-night screenings.

Nick’s memoir takes us from managing such landmarks as the Screen on the Green, and the advent of the European art house cinema, through the neighbourhood theatres – he managed the Hampstead Classic during the 1980s – as well as sleezy soft-porn cinemas in Soho.

Nick points out that for the viewer, going to the cinema has not really changed very much. The seats may be more comfortable, the sound system louder and cleaner, and depending on where you are, overpriced posh nuts may be on offer in place of overpriced stale popcorn.

But while the experience of the bum-on-the-seat may be the same today as it was 50 years ago, what goes on behind the screen is unrecognisably different.

“Cinemas do not need a projectionist with traditional skills anymore,” he says. “The film is supplied on what is effectively a very large data stick, with the film and adverts downloaded on to it, which is then attached to a ‘projector’ and an operator presses play.”

This is cheaper and has made celluloid on a reel a rarity in cinemas around the country.

And the commercial model has also changed beyond the wildest imaginations of the most left-field cinema moguls.

Ticket sales no longer earn studios anything like what they used to in terms of percentage of income. Streaming has come in on top of the VHS and DVD markets.

“So traditional cinema-going, as a regular habit, belongs nowadays mainly to only two classes of people,” states Nick. “The first are the well-to-do middle-class metropolitans who have discovered that their local small art cinema, in the unlikely event that it has survived at all, has now had an extensive makeover of both content and facilities.”

He points out the trend for specialist programming. They include Q&As with actors, directors and writers. There are screenings of theatre and opera, as well as other one-off events.

The other major demographic is a throw back to cinema’s golden age: males aged between 14 to 25.

“They like to take dates to the pictures… and stories that involve plenty of explosions and screaming will draw into the hall still. If these noisy titles can be designed to be tolerable to parents or younger teens in addition, then the chances of a Harry Potter / Jason Bourne-type hit are much increased.”

While Nick’s memoir focus on what could be seen as a niche topic, it’s all the better for it. His Everyman approach to describing the daily grind – organising an ushers’ rota, taking a delivery of choc ices – to the moments that stand out, such as finding two women close to death on the back row of a show, Nick’s skill is to make the everyday seem extraordinary and his skill with the written word makes each anecdote compelling.

On a wider level, Nick charts a period of immense change in the number one cultural and social movement of the 20th century, the biggest mass media of the age and one whose influence crosses every aspect of recent history is so big to be immeasurable.

Nick was one of those many employees who played a key role bringing the escapism of the silver screen to the masses hungry for some Hollywood glitz sprinkled on the worn-out sticky carpets of the flea pits Nick managed.

• Reel Life Behind The Screen: A Memoir. By Nick Scudamore, www.troubador.co.uk, £12.99