Spies at the Isokon

Conrad Landin reviews the extraordinary story of two Communist activists who lived in the same NW3 building but never met

Thursday, 26th September 2024 — By Conrad Landin

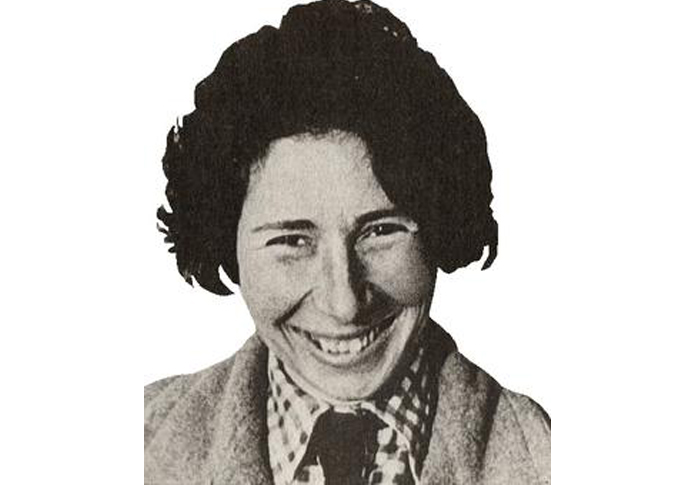

Edith Tudor-Hart

WHEN Ursula Kuczynski “stepped along the eggshell walkway” of the Isokon flats in Lawn Road, Belsize Park, in 1934, “she was not the only pregnant spy in residence,” Maryam Diener writes in Parallel Lives.

Had Kuczynski known of the existence of Edith Tudor-Hart, the two women “might have befriended one another, joined streams to form a single flowing river”. Yet in spite of their shared vocation of Soviet spycraft and close physical proximity for a time in the 1930s, no meeting between the two women was ever documented.

This small, elegant and understated cloth-bound volume tells the extraordinary story of two extraordinary women.

Tudor-Hart was born to a Jewish family in Vienna, studied photography at the Bauhaus and became a nursery teacher and Communist activist. She married the doctor Alex Tudor-Hart and fled Austria for England in 1933, where she worked as a photographer.

Meanwhile, she collaborated with the spymaster Arnold Deutsch, whom she had met in Vienna, to recruit Kim Philby as a Soviet agent. She later acted as a courier for him and other members of the Cambridge spy ring.

Ursula Kuczynski

Also from a Jewish background, Kuczynski grew up in Berlin, the daughter of a famed demographer and a painter, and joined the Communist Party of Germany as a trainee librarian. In the early 1930s she left for Shanghai, where her husband Rudolf Hamburger found work as an architect.

It was there she met fellow German émigré Richard Sorge and the bombastic American writer Agnes Smedley, both working as journalists as a cover for their spying activities. While caring for her beloved son Micha, Kuczynski assembled Soviet intelligence networks in support of Communist partisans in Shanghai, Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Peking – travelling to Moscow at one stage for spycraft training.

Renowned for her expertise in radio operations and Morse code, she was secretly made a Red Army major and received the Order of the Red Banner in 1937. Yet Kuczynski’s biggest feat was yet to come. Having relocated to Britain during the Second World War, she acted as courier for the “Atomic spies” Klaus Fuchs and Melita Norwood, transmitting state secrets from a series of cottages in Oxfordshire.

Diener, a multi-lingual Iranian-born novelist and publisher, has deployed the tools of fiction to explore how these two women came to make such bold life choices. Mainly, of course, in fierce resistance to the ones that Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and the post-war Western powers sought to make on their behalf.

The book draws on extensive research and source material to imagine Tudor-Hart and Kuczynski’s innermost conflicts and dilemmas, as they juggled their unwavering political commitment with the demands of romance and motherhood. She seeks to assess them on their own terms, leaving the narrative largely free of the inevitable value judgments which characterise traditional spy biography.

The Isokon flats in Hampstead [Justinc_CC BY-SA 2.0]

Parallel Lives is also a story of place, and one in particular: the Isokon, designed by Canadian architect Wells Coates for furniture entrepreneur Jack Pritchard and his psychiatrist wife Molly, and whose first residents included Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and many of his émigré milieu. Kuczynski’s family and Tudor-Hart’s sister-in-law Beatrix were both early tenants at Lawn Road.

While avowedly a “work of fiction”, with details “changed, condensed, or imagined by the author”, Parallel Lives often shows signs of a tension of genres. Emotive scene-setting is interspersed with passages of unimpassioned narrative history, each debasing the other. Sections of reported speech can be stilted and fundamentally unilluminating. And no-one “grabbed an onion soup” in the 1930s.

Yet Diener captures well the particularity of Tudor-Hart’s photographic eye as she snaps around Isokon before retreating to her studio on Haverstock Hill, “filled with the acrid, metallic smell of chemical developer”. As we observe the camera as camouflage, Tudor-Hart’s skill in staying undetected at the height of her clandestine activities becomes easier to comprehend.

For both her and Kuczynski, spying was both a retreat from the world and its fates, and an embrace of them – underpinned by not just fear of nuclear war, but hope for a brighter future. Both women would, of course, eventually be branded traitors. Ninety years after they crossed paths at the Isokon, Diener’s book shines a light on the complicated negotiations that allowed them to stay true not only to their cause, but to their inner selves as well.

• Parallel Lives. By Maryam Diener. Quadrant Books, £12