Seeing Red

Arrested in China in 1967 and accused of being a spy, CNJ founding editor Eric Gordon – who died last week – spent two years under house arrest with his family. His son Kim Gordon, just 11 at the time, recalls those dark days

Thursday, 15th April 2021 — By Kim Gordon

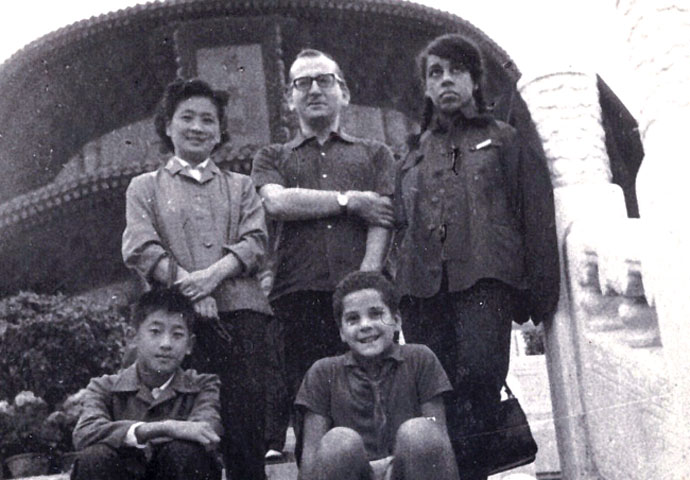

Eric Gordon with his wife Marie and son Kim, pictured in Peking in 1966 with a work colleague

I was 11 years old and it was about 11pm when the terror of the Chinese secret police was visited upon me, my father Eric and mother Marie. We were all on a train crossing the north China plain on the way to Hong Kong and then the UK after two years living in China. It was November 5 1967.

The police had come to arrest Eric and detain us as part of a spy hunt at the height of the Cultural Revolution that Chairman Mao had unleashed.

From the train we were bundled separately into cars and in convoy under armed guard taken back to Peking to a hotel and a 13ft by13ft room where we were locked up incommunicado from the outside world for nearly two years.

During this time Eric was only allowed out of the room for interrogations in a similar room opposite that housed the guards and Marie not allowed out at all. I was taken, under guard, for a 60-minute walk once a week. The only other time Eric left the room was to hospital for urgent surgery on a malignant tumour he developed.

This all happened 54 years ago. It is now hard to believe it really happened. “Two years: Is it really possible?” Eric asked in his book Freedom is a Word written on his return to the UK.

But it was.

Eric, who was a journalist and a communist, had taken us to China two years earlier. He had a yen to travel, and witness world events. China was then in isolation, with fewer than a thousand non-diplomat foreigners in the whole country of 700 million.

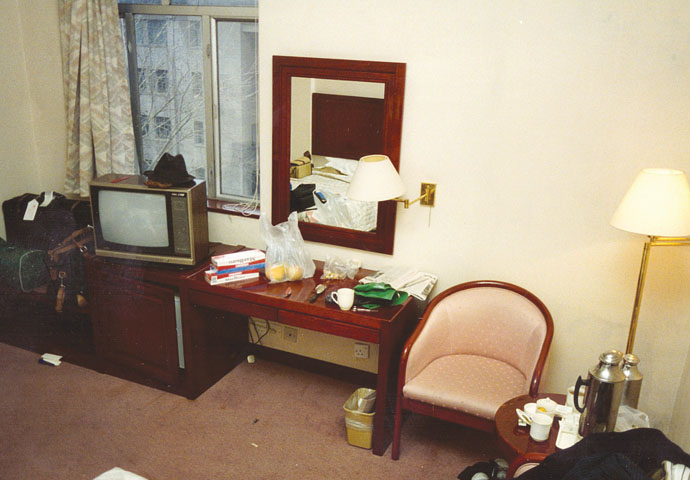

The hotel room in which the family lived for two years

Within months of arriving we were embroiled in the tumult of the Cultural Revolution. Mao launched a mass campaign encouraging student and school-age Red Guards to attack his own government’s leaders and the managerial class that ran the country.

Eric supported Mao and thought the revolution was an expression of real people power. He took part in the office meetings and we all attended the million-strong rallies of Red Guards in Tiananmen Square. He then enthusiastically started collecting material for a book in praise of the revolution he wanted to publish on his return to the UK.

But the revolution was a bloody affair; millions died at the hands of the Red Guards. From the window of Room 421, where we spent most of our detention, we witnessed the untrammelled power of the Red Guards. We saw the parades of victims frog marched down the street, arms pinioned, dunces caps on heads being punched and kicked. So when the interrogators threatened him, he knew what could lay in store. To underline the point they handed him the People’s Daily front page about a British man recently sentenced to three years prison for “spying”.

He also knew the power of bureaucrats and managers in China. He knew that staff from the dorm complex where we had lived and his own workplace had been sent to labour camps for criticising bureaucrat managers.

Within days of the arrest the Public Security Bureau (PSB) interrogators were pressuring him to confess. Because he knew the Chinese legal system relied on confessions and being well-read in Mao’s writings he was able to craft a well-written confession about being a sort of unwitting spy.

Eric Gordon in front of the XinQiao Hotel on his return many years later

As a journalist he was planning to write a warts-and-all story about the revolution. However, he “confessed” that readers and others might take a hostile view of Mao and China from such a book. But the interrogators wanted more – to inform on anyone he knew in China for their critical views. He refused and after six months trying to please the interrogators – and being rewarded with reasonable hotel food – Eric decided to stand up to the PSB and withdraw all previous confessions”.

He said he couldn’t accept being portrayed as someone who wanted to damage China or the communist ideal to which he was emotionally wedded having grown up in a poor Jewish working-class family in Manchester.

Along with a stream of written rebuttals he had numerous stand-up rows with the guards and interrogator. The PSB retaliated – putting us all on a semi-starvation diet of rice, boiled cabbage and coarse bread; no sugar, fruit or fresh food resulting in rapid weight loss and stomach problems for my mother.

The main enemy in Room 421 was boredom only overcome with a strict daily timetable of lessons for me using the dictionary and atlas we had with us; reading and rereading Wuthering Heights and Oliver Twist, singing and story telling.

But it was the discovery of a tumour behind his left ear 16 months after our arrest that led to the final confrontation with the PSB. Eric went on the attack accusing them of being anti-Maoist, cruel and even fascists – a huge insult. He criticised them for being sexist in their attitude to Marie and being anti-working class – for making his crippled working-class mother-in-law suffer even more by not knowing where we had disappeared two years earlier. All the time quoting Mao back at them.

On one occasion after dressing-down the interrogators he stormed out of the room leaving them agog. As he said in his book: “I was fighting not just for Kim’s freedom but the principles that deeply mattered to me – justice and the rights of the individual.”

At one point he shocked the interrogators even more than usual by loudly declaring: “Right is on my side”. He demanded they charge him as a spy and jail him. During this confrontation the chief interrogator using bureaucratic obfuscation tried to recast us not as prisoners but as “uncommon guests”.

As 1969 drew to a close it seems the PSB had decided to get rid of us. The international stink of my detention in particular may have been a factor. More than 50,000 Christmas and birthday cards following a huge campaign for our release by Eric’s brother Jeff and his father Samuel.

And so over three days Eric and the chief interrogator negotiated the wording of a “confession” where he admitted being anti-Marxist, arrogant, bourgeois, wrong but never a spy, unconscious or otherwise.

But he felt guilty about this compromise, that he was betraying the months of battle with the PSB which he saw as a fight against “all the dark totalitarian forces in the world. Ours had become a cry of protest from the crowd, the underdog, the people who are always being pushed around.”

So in October 1969 we were deported from China. Eric then spent the rest of his life fighting for the underdog against what he detested most – the unaccountable face of bureaucracy and corporate power.