Sawdust memories

An encounter with a towpath racist set Emma Goldman trawling her childhood for a ripe and meaty response

Thursday, 11th August 2022 — By Emma Goldman

WHEN I was nine, I called myself George. My family never remembered to use it. But I didn’t want to be a girl. In those days, the girls I found in books wore frilly dresses or prepared picnics. I preferred boy activities like climbing trees, building camps, and sleeping under the stars with my friend who called herself Bill. So, we were boys. And one day, I was vindicated.

It was a late summer afternoon. My mother had sent me into town to collect the weekly bone the butcher saved for our dog.

The town butcher was known for his “foul language”. But as my parents never explained the term, it remained undefined, holding with the butcher a mysterious glamour. I ran the mile along the lane.

My feet were bare. Having rough soles rejected the soft life of a girl. I ran past the farmhouse gate, behind which hissed the six, long-necked geese my mother said guarded it, then the dilapidated old place rumoured to have been the summer retreat of Disraeli.

It was now used by local hippies, including my much older brother, when parents got fed up with them dossing at home.

I was a slender, nimble child, in the county gymnastics team, and got to the butcher’s shop quickly. It was there he uttered the words.

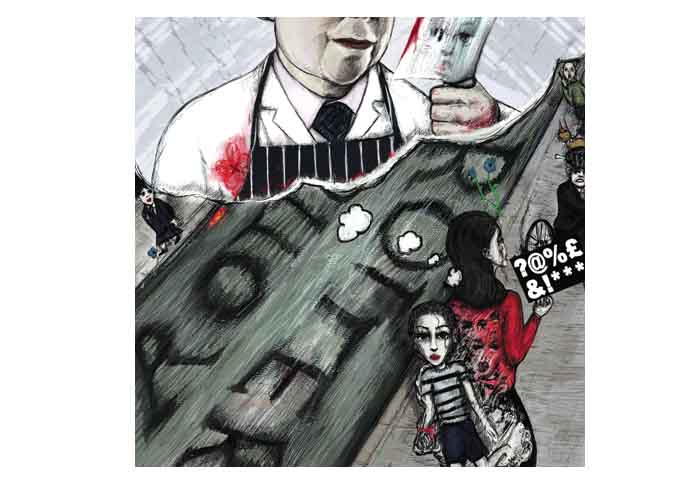

“And what can l do for you,” he asked – looking at my stripy T-shirt and navy towelling shorts, my dark hair pulled back and bare feet on the sawdust of his floor – “young man?”

The butcher had heavy jowls. He wore an apron splattered with blood. He had large white hands that gripped what looked like an axe about to chop the meat on the board.

I hurried home light-footed, the bone wrapped up in newspaper under my arm, to give my parents a superior smile. I never told them what the butcher said.

Instead, I kept it as a secret close to my heart. At the time, I believed he had mistaken me for George but, in hindsight, I see it more as a paternalistic acknowledgement of what he saw I wanted to be.

I soon grew up and away and returned to being Emma. But I never forgot him. Over the carcasses and the sunlit, sawdust floor, the foul-mouthed, kindly butcher had affirmed me.

Yesterday, being seen as something different happened again, only this time it sprang not from generosity.

My canal ride to work takes me a past a variety of Londoners. Joggers, a person rolled in a sleeping bag inches from the water, dog walkers, and the old man living under a bridge who listens to the Today programme and shouts at the presenters. “He’s a lying bugger. Stop pussyfooting around.”

Then there is Wild Pedal Man, who veers from side to side on his bike, feet bare as mine when I was George in the lane, knees racing up to his chin and back again, one hand on the handlebars, the other round a bottle of beer. One morning, I scrambled against the wall of the tunnel to let him pass.

“Even a dog has a better sense of direction than you!” he shouted with an incoherent face. And yet generally we seem a courteous lot, making way for each other. There is even the odd flirtation as when an exceptionally good-looking man carried my bike over a fallen tree and looked deep into my eyes. “I’m your Superman, right?”

But yesterday, as I meandered in the sun, a cyclist of a completely different sort came out of a tunnel.

“Left!” he sneered. “In our country, we ride on the left, madam. If you don’t like it …”

The privilege afforded me by arbitrary accident of birth and heritage means I have never hitherto been on the receiving end of this kind of talk.

I thought of all the people who have been. Those told to “go back to where you come from”. My own Jewish grandparents, even, in the East End of the 30s.

That’s when the butcher slid into my mind. The decades-gone butcher and his legendary foul-mouthed language. And defying time, close on his heels, the image of Wild Pedal Man, knees going faster and faster, up to his chin, faster, faster along the canal with his dirty, splayed toes and easy fluency of insult.

Finally, he and the foul-mouthed butcher became one.

A woman and her trotting Pomeranian looked at me curiously as I let my insults fly. Radio Four Shouter paused. Two teenage schoolgirls sniggered. At first, even the water drew back. But then, recovering itself, it took my words and chased the man, flinging them, drenching him in language, so that his other victims past and future were in some small way avenged.

• Emma Goldman is a writer and English teacher at Central Foundation Boys’ School in Islington