Ring master

Long forgotten, boxer Frankie Lucas’s reputation has been restored thanks to a new play, writes Dan Carrier

Thursday, 25th May 2023 — By Dan Carrier

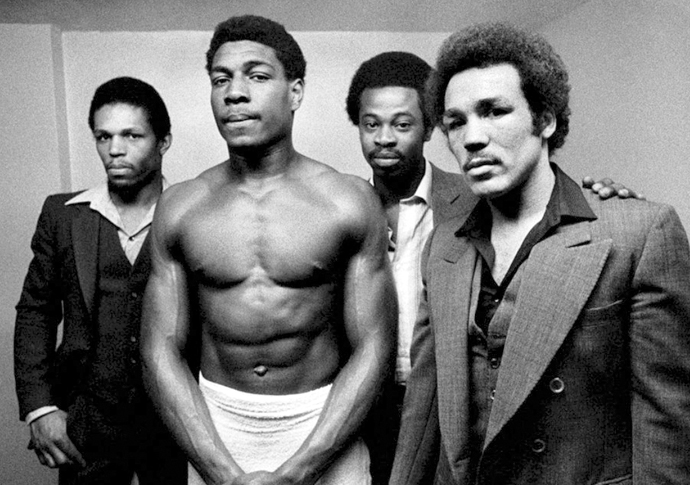

Frankie Lucas, right, with Frank Bruno [© Chris Moyes]

FRANKIE Lucas trained hard and when he got in the ring, he had that instinct that gave him the edge.

In the early 1970s he proved himself a contender – underlined by the powerful array of punches he employed in the second round of the middleweight final at the 1974 Commonwealth Games.

Up against Zambian boxer Julis Luipa, Lucas, from Queen’s Crescent, found a combination that put his opponent on the canvas and scooped him gold.

But what should have been the start of a glittering career instead became a story of missed opportunities, racism, illness and obscurity. Now Frankie Lucas’s extraordinary story can be told – just two weeks after the former champion died in a Kentish Town care home.

First-time playwright Lisa Lintott, 62, has adapted the true story of the boxer for the stage – entitled Going For Gold, it is a story that is personal to her.

Lisa grew up in Maitland Park. “My mother, Rose Hollingsworth, ran a shop next to the Lord Southampton pub,” she recalls.

Champion boxing trainer George Francis had a gym at the Load of Hay pub in Haverstock Hill, a stone’s throw from Lisa’s home.

“It was always quite the talk,” she says. “John Conteh trained there and everyone loved him. He was like our version of Muhammad Ali. He was charismatic, nice – and was a great boxer.”

Frankie Lucas lived in Southampton Road.

“Frankie was well known. He was a bit of a character,” she says. “I worked in the shop after school and he’d come in. He had an aura. He was quiet, polite and he had this way of staring at you as he spoke. As a kid, it could be quite off-putting.”

Frankie would buy the same ingredients every time he popped in.

“He’d always ask for ox tongue, liver sausage, rolls and milk,” she recalls.

Frankie moved to London from St Vincent aged nine. As a teenager, his ringcraft was obvious. In 1972 and 1973, he won the British Amateur Boxing Association’s middle weight title.

But he was not selected to represent Britain in the 1972 Munich Olympics or the 1974 Commonwealth Games. Instead, Alan Minter, who Frankie had beaten in the London ABA championships, got a shot at the Munich Olympics and would win bronze and national fame.

Aged 18, Frankie recalled how he watched Minter fight his way into the medals with tears in his eyes.

Then Carl Speare – who Frankie had defeated for the title in 1973 – was chosen for the Commonwealth Games.

It was a scandal, but Frankie would come out on top.

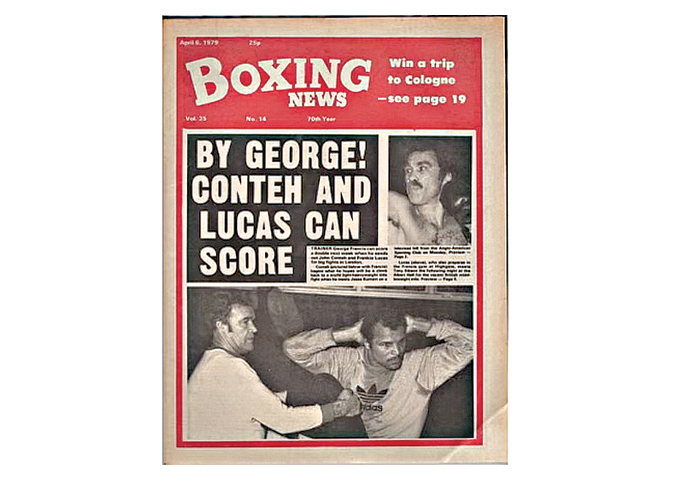

Frankie and John Conteh make the front of Boxing News

Police officer Ken Rimington, who coached at Frankie’s club, heard he had been overlooked and decided to help.

Knowing Frankie was from St Vincent, Rimington set up a boxing association for the island. Frankie competed at the games in New Zealand under their flag as their only athlete.

Frankie progressed, battering Speare in the semi final and going on to scoop gold.

Frankie joined Francis, turned professional and challenged twice for the British title. Then he disappeared from view.

What happened next has taken some digging by Lisa.

The boxing fraternity believed for many years Frankie had died, but in 2002, his fellow Francis stable mate John Conteh saw that a man jogging on the Heath could be no one but Frankie. He discovered the fighter had remained in north London – living in the same house – but long periods of ill health had meant he had become a recluse.

Frankie died aged 69 last month. He had been diagnosed with cancer, but lived longer than doctors predicted – long enough to hear all about Lisa’s play.She discovered Frankie did not enjoy a good reputation: he was considered “difficult” – but he was a terrific boxer.

After some success as a professional, life got complicated. There were reports he was acting “strangely”. Frankie had become unwell, and would spend periods in hospital when his mental health was poor.

“I heard something along those lines many years ago, and then I did not think of him again,” says Lisa.

But Frankie would re-appear in Lisa’s life in an unexpected way when she enrolled on a writing course.

“A piece of homework was to pen a short story about food,” she reveals.

“I don’t know why I thought of it, but Frankie coming in and asking for half a pound of ox tongue seemed to be a great opening line.

“I thought about our shop – the food tins, a sack of spuds and a bit of fruit. You’d take the liver sausage, and put it on the slicer, cut the slices and then weigh it up on the scales. I loved writing that story – I remembered the shy little girl hiding behind the counter. I wondered what happened to Frankie, and I started researching his life.”

She was deeply moved by what she discovered.

“His story had to be told,” said Lisa. “It is like a black British Rocky.”

Despite his talent, the boxing world was not going to help.

“He struggled to get fights. There was a belief that black British boxers did not draw crowds,” says Lisa.

“The sport was run by a cartel and they had not forgiven him for beating up Speare.”

Lisa turned Frankie’s story in to a short film and it enjoyed success at USA festivals.

It led to her getting in touch with Frankie’s son, Michael.

“I saw a message from him saying his dad was alive,” she says.

Frankie had moved to a care home in Kentish Town.

“I wanted to turn it into a play with his blessing,” she adds. “Frankie remembered me and my mother.”

After completing a playwriting course at the Central School of Speech and Drama, Frankie’s life became her debut play.

“I had seen it as a tragedy – but instead I found something else entirely,” she added.

“It was about family, love and legacy.”

The play, which is due to be read through by actors at the Chelsea Theatre next week, has garnered a lot of interest.

“The boxing world is close,” she says.

“One of the nicest things is how boxers discovered he had been living quietly in Maitland Park and wanted to help, and honour his memory.”

• Going For Gold is at the Chelsea Theatre from 5-8. See chelseatheatre.org.uk/whats-on-2/