‘People used to look at me suspiciously and say, did you really take this?’

Angela Cobbinah talks to the man Simon Schama called one of ‘Britain’s great photo portraitists’

Thursday, 30th January 2025 — By Angela Cobbinah

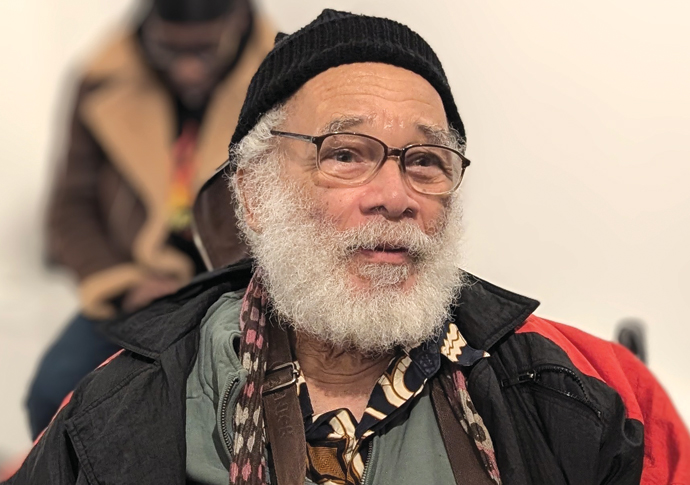

Charlie Phillips

WHEREVER Charlie Phillips rocks up you can always be sure of a crowd, especially if it’s in Notting Hill. This is where the veteran photographer lived after coming to Britain from Jamaica as a child of 11 before being priced out as an adult and exiled to Mitcham. Having enjoyed an 80th birthday bash at the Tabernacle in November, he was recently back again, holding court at his recent exhibition at the Muse Gallery in Portobello Road, Charlie Phillips: Past and Present. There was a real buzz about the place and among those who turned up were the singer Rita Ora and fashion industry luminary Camilla Lowther, both denizens of the Hill.

Despite a recent stroke, Charlie was his usual forthright self as he gave an amusing running commentary on the images on show in a live stream for Portobello Radio. Most were from his days in Notting Hill where, having acquired an old Kodak camera and a DIY developing kit as a youth, he began to document an impoverished but lively neighbourhood that was emerging from the shadow of the 1958 race riots. The result is an unrivalled catalogue of intimate portraits of ghetto life set against the backdrop of an area convulsed by demolition works to make way for the Westway flyover. It was a long ago world where crumbling three-storey houses that go for millions today could be bought for £1,000.

Charlie was mostly familiar with those he photographed, like his friend George in Marlon and George, a lovely 1972 shot of a small boy with his father taken in Acklam Road, and the boozers in the Piss House Pub, one of an eponymous series from 1969 taken in his father’s favourite watering hole, the Coville.

“It was the first place where I had a shandy but when I was younger I used to wait outside for my daddy who would drink Mackeson Stout there,” he explained. “There was a large Irish community in the area as well and we used to share the pub with them. It had a real community spirit. We would get along because the Irish kids used to go to school with us and also get a lot of abuse. Remember those signs ‘No Coloured, No Irish, No Dogs’?”

He bumped into the subjects of what is probably his most well known photograph, Notting Hill Couple, at a party in 1967, a beautifully framed shot of boyfriend and girlfriend staring intensely into the lens that historian Simon Schama chose for his Face of Britain book and TV series, while everyone knew Duke Vin, the legendary “soundman”, whom Charlie photographed looking dapper in a trilby and clutching two records. “Duke Vin was the person who first introduced the sound system to this country but he has been left out of British musical history,” he commented. “My photographs are a way of keeping our untold history alive.”

Charlie Phillips’ photo, Notting Hill Couple [Akehurst Creative Management]

What is Notting Hill without Carnival? The exhibition featured Carnival photos taken in the 1960s, one of them reproduced as a mural in Portobello Road in 2023. However, a few days later it was mysteriously painted over. “I was devastated as it documented our presence in Notting Hill, but we are trying to get it reinstated,” he announced.

Adventurous and blessed with an engaging personality, Charlie joined the Merchant Navy before travelling round Europe. He settled in Italy where he became a celebrity snapper for the likes of Harper’s Bazaar, Italian Vogue and Life. His work took him took to Zurich where he photographed Muhammad Ali training for his bout with German champion Jürgen Blin in 1971 just months after his draft evasion conviction was overturned. “Ali accommodated me a lot and always called me ‘Jamaica’ because he said he’d visited Jamaica and had had a good time,” Charlie told us, introducing his Ali series that included the iconic “I’m back” mug shot.

Returning home in 1974 with a bulging portfolio and buoyed by an exhibition of his Notting Hill photos in Milan attended by master lensman Henri Cartier-Bresson, Charlie had high hopes as he went round to editors and galleries. But to his dismay there were no takers, no commissions. “People used to look at me suspiciously and say, did you really take this? Or they would tell me the market’s flooded or there’s no market for it. Seriously! My work was suppressed by a cultural elite who decide what’s seen and not seen.”

Demoralised, Charlie stuffed his work under his bed, earning a living selling roasted corn on the cob in Portobello Road Market before opening a successful US-style diner in Wandsworth called Smokey Joe’s.

In those days, it was easy to get accommodation and the frequent moves saw him lose many of his photographs, including those of Jimi Hendrix back stage at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, his last UK performance before his death. “I had a row with a girlfriend and she threw out a lot of my photography too,” he added ruefully.

Things began to look up when his monograph, Notting Hill In The Sixties, was published in 1991, leading eventually to his first major UK exhibition at the Museum of London in 2003. As his star rose, his images entered the collections of the V&A and the Tate and shows have included How Great Thou Art, based on Charlie’s work as the honorary “dead man’s photographer” at Caribbean funerals.

Schama has described him as one of “Britain’s great photo-portraitists”.

But success has not necessarily softened Charlie’s view of the arts establishment whom he accuses of “tick-boxing” and being fixated on Black History Month. Praise is reserved for Tim Burke, the arts anarchist who built pop-up galleries in Notting Hill out of materials like milk crates and plastic bottles to showcase his photography when it remained largely under the radar.

Pointing to his picture of Burke, Charlie said: “If it wasn’t for Tim I would have probably ended up working as a porter or washing dishes.”