‘People remember the moquette – even if they don’t know they do’

Dan Carrier talks to author Andrew Martin about his latest book... and where he gets his... ahem, material from

Friday, 24th October 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Andrew Martin, author of The Moquette Mystery

MAY Mitton lives in a small bedsit near England’s Lane, Belsize Park. She works in a department store in Tottenham Court Road, and the young woman, who moved to London from her native Halifax in early 1938, one day found herself in a baffling situation: a brief chat with a police officer turned her detective, on the trial of a murderer who has bumped off an artist.

This is the premise in the latest novel by Highgate-based writer Andrew Martin.

Andrew is behind the Jim Stringer series of 10 books, with stories set around his first love, the railway network. In his latest offering, he has drawn on a field he has a peculiar speciality in: the life and times of moquette.

But what is moquette? It is a piece of visual artistry that is so ubiquitous across the UK that surely everyone knows of it, but without realising: it describes the carpet-like seat coverings with abstract designs that grace our transport network. From buses to tubes to trains, the hard-wearing, patterned material – often woven in colours to hide the muck and wear – are an integral part of public design, and a niche topic Andrew is an expert in.

The author of history books on railways, it was a natural step to combine his background in crime fiction with his research into the aesthetics of travel in the UK. And the outcome is a brilliantly readable murder mystery, featuring May as an amateur detective.

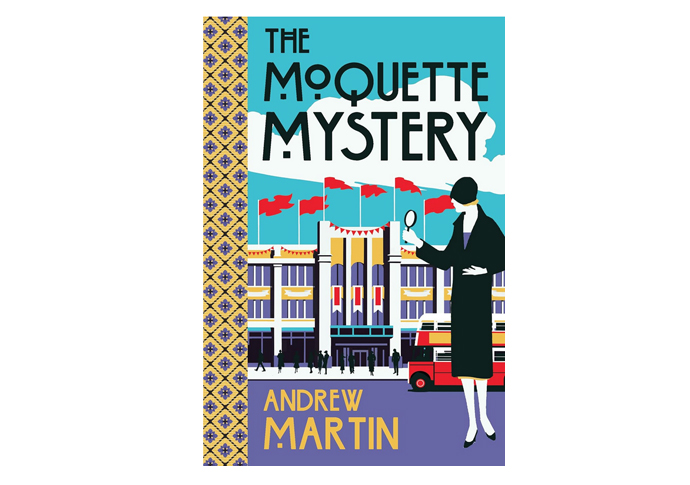

The Moquette Mystery sets May out to uncover the truth over the death of a designer and artist responsible for tube posters persuading passengers to move to Metroland, home counties countryside or the Cornish Riviera on the rail network.

“I have written a number of historical crime fiction books, and most have train journeys in them,” says Andrew.

A Sherlock Holmes fan as a child, crime fiction has always appealed for its framework.

“I like the way with crime novels it is pretty obvious if it works or not. It is not as nebulous as literary fiction, which is open to subjective judgement. I like the rules,” he says.

Andrew hails from Yorkshire – a county that plays a role in the plot – and it was a 1970s childhood riding trains that first piqued his interest.

“I am not interested in the engineering side, but the social history and aesthetics,” he reflects.

This led him to write a book that at first may seem niche – but its popularity reveals the role publicly constructed aesthetic design impacts on us all. In Seats of London: A Field Guide to London Transport Moquette Patterns’ he studies the evolution of an important piece of public art history.

“People remember the moquette even if they don’t know they do,” he says of the seat coverings. He points out how the UK enjoys a tradition of decorated seating that has the same properties as sheep’s wool – warm in winter and cool in summer.

“It is a Cinderella art form,” he says. “It is a French word that means light carpet and they have been used on the London Underground since the beginning.”

The novel takes place in those dark, immediate pre-war years of 1938 – which also happened to be a glorious era for public transport in London with the Underground designs headed by the legendary Frank Pick. Pick had commissioned the Harry Beck tube map, and played a key role in how new tube stations looked and the design ethos found across the network.

“In the late 1930s, tube design could be considered at its peak,” says Andrew. “There was the introduction of new tube trains called the 38 stock, and it had beautiful red and green moquettes, Pick thought the red symbolised the city and the green the countryside, and the tube took people there and back. He thought green was serene.”

As May criss-crosses the country armed with a piece of moquette cut from an unknown source – a key clue – Andrew reflects on the impact something as utilitarian as a seat cover can represent.

“Some of them were exceptional – you could look at the pattern for ages and still find it hard to discern the formula, often using very few colours,” he adds.

[Dave Sandford_CC BY-NC 2.0]

And these seats have had an unconscious impact on generations.

“Moquette produces an almost Proustian memory trigger. If you go to the London Transport Museum, you can buy cushions and sofas in moquette. A popular version is called the D78, used on the District line in the late 1970s. Now, the District line goes to prosperous parts of London – and it makes sense that people who grew up along the District line would now be able to afford to buy imagery that contains a memory for them.”

And how moquette evolved is a tantalising sign of the mores of each decade.

“In Edwardian times, the moquette would feature detailed floral designs. It would be the general manager’s wife who would say I would like a rose pattern. The Edwardians made them as pretty as possible,” he says. The interwar designs reflected changing tastes.

“They became more geometric in the 1920s and used a lot of brown and teal. People using the tube were often dirty – it took chimney sweeps to work and back, so they went for darker colours.”

And of course it is the people who sit on moquette seats that also fascinates a writer, adds Andrew.

“You get to look at people, study them,” he says. “I ask myself: what does that person opposite me sound like? What sort of voice would they have? I have occasionally found a reason to ask someone a question – ‘Is this the right train for High Barnet?’ – because I want to hear their reply.”

The richness of this tale – and the believable characters, whose lives he imagines nearly 100 years ago – stems from his research.

“I look at old photographs,” he adds. “You get an immediate sensation of the scene, you get an immediate sense of the people. And by looking at a face, you begin to create a character.”

It also appeals to his sense of style.

“I like the elegance,” he says. “You’d get someone digging a road wearing a collar and tie – it may be filthy, of course, but dress code was common.”

He adds that trains and crime fiction have an entangled past.

“Trains were actually the origins of crime fiction,” he says.

“Station kiosks would sell slim stories that were sensational – they had to hold your attention. They were short stories designed to be gripping.”

And the experience of train travel – particularly with old-fashioned enclosed carriages – lent itself to the crime novel, he adds.

“You get strangers travelling together: in a way it is similar to the country house murder – different characters in a confined setting. That’s the perfect start for a murder mystery.”

• The Moquette Mystery. By Andrew Martin, Safe Haven Publishers, £9.99