Peace work…

A new book about interwar art by Camden Town-based art historian Frances Spalding wears its scholarship lightly, says Michael White

Thursday, 15th September 2022 — By Michael White

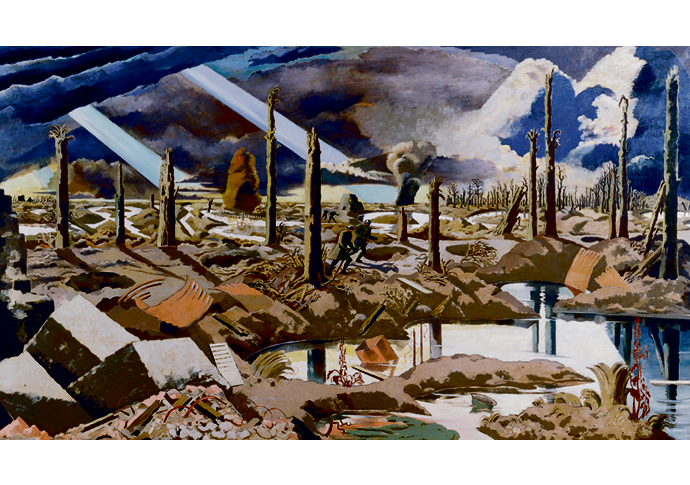

Paul Nash, The Menin Road, 1919. Oil on canvas © Imperial War Museum (Art. IWM ART 2242)

BETWEEN the end of the First World War and the start of the Second was a brief window of peace that lasted barely 20 years.

But for the visual arts in Britain it was busy – with a host of major painters, sculptors, architects, designers looking forward to the new or looking back to the familiar, establishing “movements” and “counter-movements”, publishing manifestos, trumpeting the virtues of Englishness or the excitement of Internationalism, and arguing the merits of the abstract as against the figurative.

A surprising amount of this ferment took place in the relatively small, ostensibly quiet enclave of streets between Camden Town and Hampstead. And accordingly, the Camden Town-based art historian Frances Spalding is in many ways ideally placed to document what happened – as she does in her new book The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars.

A substantial work, handsomely illustrated, the dimensions of the book might be off-putting: it won’t slip into your pocket for a train ride. But it’s actually a clear, compelling read that wears its scholarship with an attractive lightness and, within its genre, could be fairly called a page-turner.

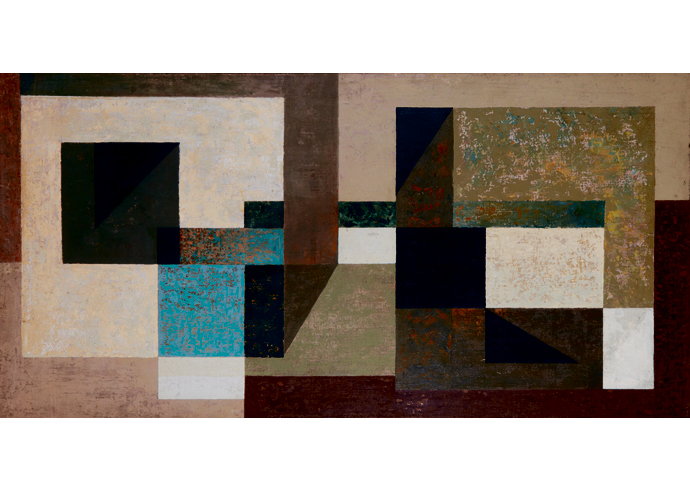

John Cecil Stephenson, Abstract Painting, egg tempera on canvas on board, 1935. Private collection. © The Estate of John Cecil Stephenson

The author is an academic of distinction, having been Professor of Art History at Newcastle University, a Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge, and editor of the lofty Burlington Magazine. But she’s also written 16 standard works of cultural biography, most of them focused on the Bloomsbury Group and their connected web of English artists in the early- to mid-20th century.

She writes with unimpeachable authority but, at the same time, tells a story for an average reader without academic jargon or pretension. And the story-telling in The Real and the Romantic has been deftly organised to sort the complicated narrative of those two inter-war decades into some kind of order.

As she says, “it’s not a comprehensive survey, more a journey through an era”. And it was an era that began at a low point in the aftermath of something that “was devastating, not just for the loss of life but loss of artistic direction, which is why you find artists pursuing such different paths with no presiding idealogy.

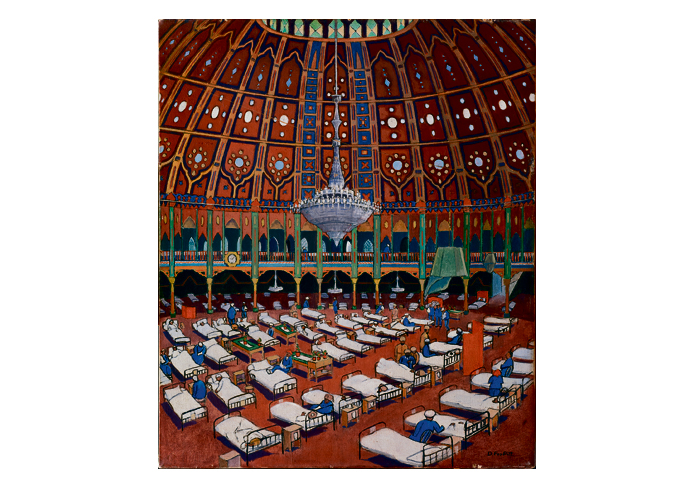

But at the same time, the War had been a significant factor in the democratisation of art. It had conveyed information through images produced by official war artists, and made them available to the public as never before. Art was no longer for the ‘toffs’ but accessible to ordinary people”.

This was a period when a group of painters could declare themselves a “movement”, write to The Times to announce their existence, and expect its readers to be interested. Which it seems they were – although they’d have been baffled by the conflicting ideas on offer as more conservative figures lobbied for a “return to order” with traditional subject matter, as a sort of balm for the recent horrors, while others saw no possibility of return and looked elsewhere.

To some degree the imagery of war with its new, grimly powerful technologies had shifted tastes against the modernist machine-aesthetic that seemed so promising in the early 1900s.

As the painter John Nash, who made his name from bleakly melancholic paintings of bombed-out terrains explained, “the justification for what I do is to rob war of its last shred of glory, last shine of glamour”.

And in subsequent years, he and his brother Paul would bring their war experiences home, refreshing the visual language of English landscape painting to produce a vision of the countryside more brittle than bucolic, sharply drawn and radically removed from the idyllic rural lushness the public had previously enjoyed.

Dora Carrington, Tidmarsh Hill, c1918. Oil on canvas. Private collection

At the same time, many artists were looking way beyond the English countryside to non-Western influences – and it’s surprising to learn how important a part in that process was played by the British Museum, where artists like CWR Nevinson found inspiration for his Hyde Park war memorial reliefs in the museum’s Assyrian collections, and where Henry Moore found prototypes for his monumental abstract forms in African and Egyptian sculpture.

Describing the excitement of his visits as “like a starved man having Selfridges grocery department all to himself”, Moore was captivated by the stillness of these museum objects, a repose (he said) “of waiting, not of death”. And the result you now see in the countless galleries and public spaces that house Moore’s extensive output.

Moore was one of the big names associated with that catchment area north of Camden Town – along with Ben and Winifred Nicholson (founding figures of English abstraction), Barbara Hepworth, and eminent visitors from abroad like Piet Mondrian. They lived and worked in the Mall Studios off Tasker Road, in Parkhill Road, in Eldon Road.

They exhibited in the Finchley Road, or at Bowman’s furniture store in Camden High Street, which had room displays enhanced with paintings by John Piper. Also, not to be forgotten, was the experiment in communal living that survives in the modernist Isokon flats in Lawn Road: a beacon for artistic refugees from Europe like the celebrated Walter Gropius and his colleagues from the Bauhaus.

Douglas Fox-Pitt, Indian Army Wounded in Hospital in the Dome, Brighton, oil on canvas, 1919. © Imperial War Museum (Art.IWM ART 323)

In her “journey” through all this, Spalding’s attempts at mapping out a route have led her to the idea that so much diverse activity can be accommodated within two broad headings: the “Real” and “Romantic” that provide the title of her book. She thinks of them as “two poles, between which there’s a conversation”. And I can only say I’m not sure how helpful a guide that proves.

But no matter. It’s a fascinating journey, all the more interesting for its twists, turns and ultimate resistance to neat summing up. Alongside the stars of the period – the Pipers, Spencers, Moores and Hepworths – it lingers over lesser names you probably won’t have heard of but are worth attention: Frances Hodgkins, Charles Sims and the severe abstractionist John Cecil Stephenson whose work has recently been on exhibition at Hampstead’s Burgh House.

Spalding tells you what they had to offer with an admirable even-handedness – she’s not the kind of hard-line art historian who says that to admire one genre of work is to dismiss its opposite. Discerning inclusivity is more her mission. And above all, it’s a mission to upgrade our understanding of a period in English art that has traditionally been undervalued by comparison with what was going on in France and Germany.

The Real and the Romantic may not be the best of titles, but it’s still a landmark book. A good read. And a must-read if your summer plans include a visit to Tate Britain or some other gallery that takes the work of English painters seriously.

• The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars. By Frances Spalding, Thames & Hudson, £35