Paper trail

As a new exhibition about our very own publication opens at Holborn Library, Dan Carrier gives a history of the press

Thursday, 17th October 2024 — By Dan Carrier

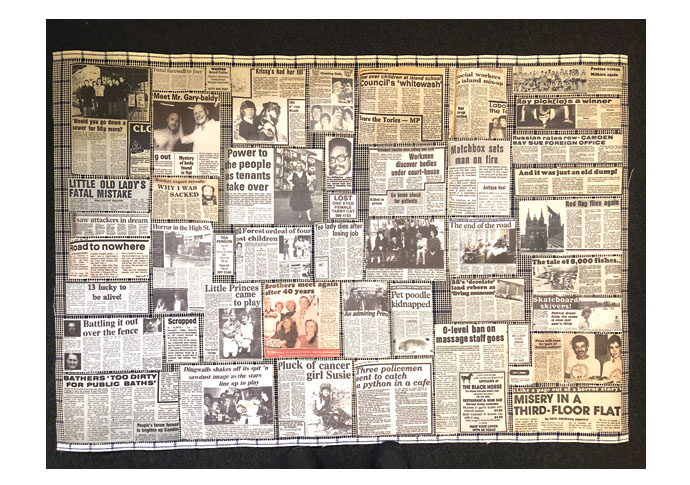

Maisie Rowe outside the CNJ offices; the background is one of the exhibition panels

MARCH 1872. A printing press in the back room of a Holloway Road shop cranked into life and the first edition of our newspaper rolled out.

The publisher, bookbinder, printer, bookseller and newsagent could not have failed to note how his business was thriving – and how often new London newspaper titles were emerging.

Why not a title for our area, they thought? So, after securing advertising, The Holloway Press and Hornsey Advertiser hit the news stands.

Some 152 years on, we are still publishing, today under the masthead the Camden New Journal – and this week, as part of the Bloomsbury Festival, a special exhibition celebrating your Camden newspaper begins at the Holborn Library.

Designed by artist and lifelong New Journal reader Maisie Rowe, it includes the story of the paper from inception to the present day, memories of colleagues former and present, a selection of front pages and a fascinating selection of stories, letters and adverts from years gone by.

“Like so many people, I have grown up with the CNJ,” said Maisie, who is from Camden Square and now lives in Bloomsbury.

The designer and artist added: “It’s been part of the fabric of life here for so long, it’s part of the furniture.

“Looking back through the archives highlights quite the impact the paper has had. Thousands and thousands of words, all about us, the community. And the range has been incredible – every edition had a piece of interest, an article that shed light or provided an example of a topic.

“They are historic snap shots, like stepping into a time machine.”

As the exhibition reveals, the founding of the Holloway Press reflected an information boom and how it was distributed in the 1800s.

While we can trace our roots to 1872, an earlier iteration came out in 1828. Called the Islington Gazette, it was subtitled “Monthly Miscellany Of Local Intelligence, Combined with Literary and General Information and Amusement.”

Distributed by C Hancock of Sadler’s Wells, and found in “news vendors in Islington, Holloway and Pentonville,” it lasted three issues. Later, in 1836, The Penny Magazine was published by a firm called the Holloway Press, where our own story started.

The rise of the newspaper industry during Victorian times was caused by a number of factors. First, more Londoners could read. In 1820, the literacy rate was 53 per cent. By 1870 it had risen to 76 per cent.

Printing improvements meant better images and prompted The Illustrated London News, the first weekly in the world that led on pictures, which dates from 1842.

These elements kickstarted a 50-year Golden Age, before competitors in other mediums such as radio.

The technical improvements, professional reporters, and new owners with axes to grind brought in mass journalism.

The writing, design, production and distribution of newspapers was becoming larger in scale, attracting investment by industrialists. The age of the baron was upon us – and with that, a less fearful state as the newspapers were owned by vested, established interests.

And as the big owners emerged, papers became partisan: while the owners used their mouthpieces to protect their interests, workers’ movements saw the need to fight their capitalist exploiters in print. Socialist newspapers enjoyed a boom, including the founding of the Daily Herald for the trade union movement.

As the age of the political pamphlet and gossip sheet gave wayto the industry we recognise today, political influence saw Whitehall scrap duty on paper in 1861, which ended historic restrictions on newspaper production.

There was a new understanding of the relationship between power and the press: the inhabitants of Parliament discovered they could not use the libel laws to censor newspapers as they had in the past.

Then there was a boom in technology: Faster presses, stereotyping, machine composing – developments led by The Times in the late 1800s included the Walter Press speeded up production, with pages rolling off at 12,000 an hour.

The Times secretly installed two away from their Fleet Street base, to ensure the printers would not cause trouble, an eerie precursor to Rupert Murdoch taking the company to Wapping.

It also made the product cheaper: in 1855, the Daily Telegraph cut its price in half to one penny and saw sales up to 160,000 a day in the early 1860s. The Times was sold at 4d in 1855, a price that dropped by a quarter in the 1860s.

Telegraph cables had a massive impact. News could come from much further afield. Reuters and the Press Association were founded in 1851 and 1873, meaning newspapers could subscribe to a never-ending churn of information down the wires. The laying of transatlantic cables brought exotic news from the Americas.

Generally from four to eight pages in size and printed on a broadsheet, the newspapers of the 1870s were packed with adverts and information. With seven columns across the page, editors seemed to be competing to squeeze as much in as they could.

The quality of the content changed as the role of the reporters developed. The age of the Men of Letters, who dominated the start of the 19th century, was over: reporters had to be professional.

In 1895, the founding of the Society of Women Journalists was another landmark. There had been a marked rise in female writers: Mirror editor WT Stead employed women on the same salaries as their male counterparts.

Stead was a promoter of the idea that a newspaper did not have to reflect the news of yesterday but the views of tomorrow. Newspapers could reflect the will of the people, run campaigns. The increased economic demands and financial benefits of owning a newspaper made an impact in the 1890s onwards: as a large commercial concern. It needed to sell. That meant entertaining and amusing, not just informing.

The content shows how society was changing, too – the rise of the national game gave sports editors a role. Women’s pages and gossip columns, celebrity and society news, politics and Parliamentary think pieces, lots of illustrations and special investigations proliferated.

Keeping it human became important: nature columns, sketches, travel writing all made their appearances, as did interviews, opinion pieces and serialised novels.

By the Edwardian period, daily London papers were on every street corner.

Our title was made part of the co-operative movement in 1982 and today, the New Journal continues to fulfil the role generations of news reporters have before us.

• Open To All, Coerced By None – the story of a local newspaper is in the Local Studies Centre at Holborn Library, 32-38 Theobalds Road, WC1X 8PA. Runs from October 19-24. Sat 11am-5pm, Mon/Tues 10am-6pm, Thurs 10am-7pm. Elements of the exhibition will be in the foyer during regular library hours