John Sweeney and the ‘arrogant’ hero who took on Putin

John Sweeney’s account of Alexei Navalny’s life reads like a thriller, says Lucy Popescu

Thursday, 16th January 2025 — By Lucy Popescu

John Sweeney, author of Murder in the Gulag [Liam Kennedy]

WATCH OUR ONLINE POLITICS CHANNEL, PEEPS, ON YOUTUBE

WATCH OUR ONLINE POLITICS CHANNEL, PEEPS, ON YOUTUBE

JOURNALIST John Sweeney has challenged dictators, cult leaders and crooked businessmen for almost half a century. The author of 16 books, including the Sunday Times bestseller Killer in the Kremlin, he has confronted both Trump and Putin face-to-face.

Murder in the Gulag is John Sweeney’s hard-hitting and accessible account of Putin’s murderous regime and his dispatch of the opposition politician and anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny, who died in an Arctic prison in February 2024, aged 47. Sweeney explores Navalny’s flaws, in particular his brief flirtation with the far right, but recognises his immense courage.

When I spoke to him about his book, he said that he considered Navalny, who he’d met and interviewed, a hero but also “arrogant”, observing that you had to be to challenge Putin.

Although Navalny was Moscow-born, his father was from Chernobyl. He spent childhood summers in Zalyssia, his grandmother’s village, 20 miles from the nuclear power plant. If the 1986 nuclear disaster had happened in June, rather than April, he would have been there. Years later, Navalny criticised the silent Soviet bosses who had driven his relatives to plant potatoes in the collective farm as if nothing had happened: “Here they were digging with their own hands with the radioactive dust falling and receiving a huge dose of radiation.”

Navalny studied law at the People’s Friendship University before taking a second degree in securities and exchanges at the Financial University, graduating in 2001. He met his wife-to-be Yulia Abrosimova in Turkey in 1998 and they married two years later.

They joined Grigory Yavlinsky’s liberal party, Yabloko, which was trying to counter the rise of Putin’s United Russia party. Frustrated by their failure, Navalny turned to the far-right Russian nationalists who, he believed, had the energy to defeat Putin’s “party of crooks and thieves”.

Navalny later dissociated himself from them, but it was, Sweeney observed, a huge mistake that would come back to haunt him. In February 2021 “Amnesty International stripped Navalny of his prior ‘prisoner of conscience’ status after it says it was ‘bombarded’ with complaints highlighting xenophobic comments that the man – who some said was ‘a vile white supremacist’ – had made in the past and had not renounced.”

The same year, the Nobel Peace Prize passed over Navalny, naming Maria Ressa, a Filipino human rights activist, and Dmitri Muratov, the editor of Novaya Gazeta as co-laureates. Sweeney believes these snubs stripped away some of Navalny’s protection: “I suspect that Putin treasured the moral failures by Amnesty and the Nobel committee, and that it made his decision to have Navalny snuffed out all the easier.”

At times, Murder in the Gulag reads like a thriller. Navalny was a thorn in Putin’s side for many years and, for Sweeney, his fearlessness was part of his charm. Sweeney describes the attempt to kill him with a Novichok nerve agent and following his recovery, the sting operation in which Navalny posed as “Maxim Ustinov”, senior aide to Nikolia Patrushev, a former boss of the FSB.

He called up Konstantin Kudryavtsev, one of the chemists involved, and asked him how they had poisoned Navalny and what had gone wrong. Kudryavtsev confirmed that they had placed Novichok in the crotch of Navalny’s underpants on the orders of Stanislav Makshakov, a military scientist.

Kudryavtsev claimed that it was only the swift action of the emergency medical team in Germany, who injected Navalny with an antidote, that had saved him. Navalny posted a recording of the conversation on YouTube. Soon after Kudryavtsev “disappeared”.

Navalny openly accused Putin of being responsible for his poisoning. In January 2021, he returned to Russia and was immediately detained on accusations of violating parole conditions while hospitalised in Germany.

One of the goals of Murder in the Gulag, Sweeney says, is to explain what made Navalny return home when he knew he was at risk of being arrested or killed.

He suggests ambition, overconfidence and a politician’s tendency to embrace risk all played a part, while Navalny’s Christian faith was also an important factor.

Sweeney argues that “Navalny was killed in large part because of the West’s appeasement of Putin.”

In an investigation by his Fund for the Fight Against Corruption, Navalny revealed that former deputy prime minister Igor Shuvalov bought two flats on Victoria Embankment, overlooking the headquarters of the British Ministry of Defence: “For more than 10 years, Shuvalov hid his apartment behind anonymous offshore companies… He misled the Russian and British tax authorities, hired lawyers to manage the asset, set up blind trusts, all to hide the fact that this particular apartment belonged to [him].”

Sweeney posits a further question: “Did anyone inside MI5, Britain’s security service, flag this up, sending out a memo saying something along the lines of: ‘I say, chaps. The Russian deputy prime minister is buying a flat overlooking our Ministry of Defence. The possibility of the Russians using this flat as a base to spy on us, to train spy cameras on who is coming and going, to use the latest in eavesdropping technology to hear our conversations is high. Are we going to stop this?’ …it is clear that Her Majesty’s Government, as it then was, took the money and allowed Putin’s creature to move in.”

Sweeney refers to Navalny as “a canary down a coal mine.” Murder in the Gulag is as much about Russia’s president as it is about Navalny and the book serves as an urgent call to the West to stand up to Putin before it is too late.

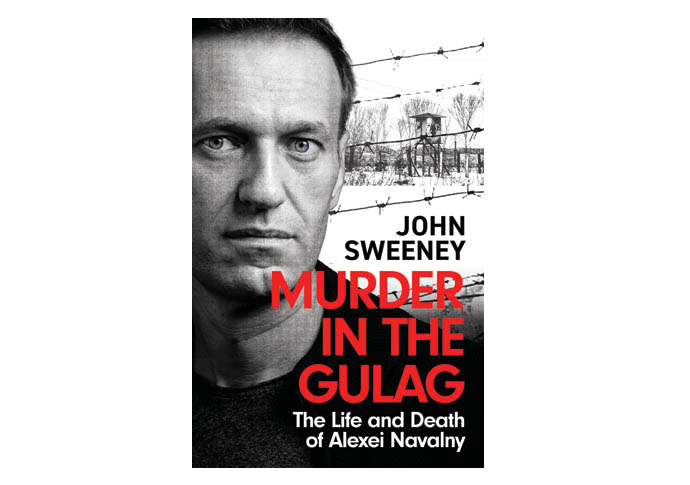

• Murder in the Gulag: The Life and Death of Alexei Navalny. By John Sweeney, Headline Press, £20