Jewel carriageway

Dan Carrier delves into the colourful history of Hatton Garden, thanks to a gem of a book

Thursday, 13th October 2022 — By Dan Carrier

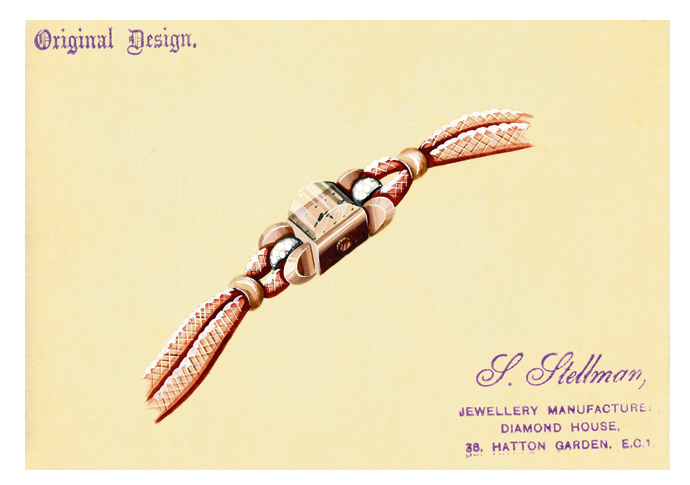

Jewellers S Stellman’s workshops

HUDDLED groups, looking at something held in the palm of a hand, were once a regular sight on the streets of Hatton Garden. And after intense discussions, a handshake – and a deal worth thousands would be sealed.

London’s precious gems and metals district has for two centuries seen trading of the earth’s riches, establishing a neighbourhood in Londoners’ minds as the only place to go for stones and jewellery.

Now, the Hatton Garden story has been comprehensively told by in a new book by Vivian Watson, who has spent a life time immersed in the culture of the patch.

His family are gemmologists and he joined in 1967, and saw first hand how the Garden operated.

Vivian begins his story 1,000 years ago – and welds it to a recent history many will recognise.

Speaking of the Garden in the 20th century, he recalls how an industry dealing with items of extraordinary value was not done behind locked doors and barred windows.

“The streets were as much a trading floor as the shops,” he reveals. “Up to 1940, many had no premises, while others preferred the freedom of the slightly shady way of operating, which suited their style of business better.

“Some brokers gave their trading address as ‘care of J Lyons Tea Shop, Hatton Garden’, and received mail there.”

The characters who traded on the pavement or in cafés and bars provided a wonderful cross section of humanity.

“Their style gave no clues to their activity. A casual observer would never imagine the extraordinary wealth that was on offer.”

The streets were full of deals to be struck.

“It was common to trade from doorways and even out on the pavement. On any given day you might find more than a dozen clusters of men engrossed in conversation,” he writes.

The Watson family in their Garden base

“The conversations may have been diverse but all of them would focus on a small folded paper packet, known as a brifka. This contained a gem the dealer was offering.

“The gems were appraised with care.

“At that time there were no third party laboratory reports, only the opinions of the parties to the transaction. A grey day was to be avoided. Trading was normally between 10am and 3pm to get the best of the daylight.”

Many languages were spoken as traders from across Europe converged – Yiddish, French, Dutch and German were as common as English.

The jewel trade took off in the Victorian period. Diamonds were discovered in South Africa and became a popular must-have for the fancy fingers of the Victorians and Edwardians.

Before this, the area had been semi-rural.

Vivian describes Holborn of the 1100s as being a “market garden, with pastures, orchards, steams and water mills”.

In the 1200s, it would become the property of the Bishops of Ely, who built a palace in 57 acres of gardens.

Its reputation was such that William Shakespeare refers to the gardens in Richard III, when he has the King stating:

“My Lord of Ely, when I was last in Holborn, I saw good strawberries in your garden there. I do beseech you, send for some of them.”

The area gained its name in the Elizabethan period, Vivian adds.

Christopher Hatton, born 1540, was a dashing young lawyer and his dancing ability attracted the attention of Queen Elizabeth. Their relationship went, as Vivian puts it, “way beyond normal protocol”.

He was lavished with titles and became an MP in 1571. “It would appear the Queen was willing to give Hatton whatever he wanted, and he had his eyes set on Ely Palace,” says Vivian.

“It was one of the finest cultivated gardens in England, and included a hall, cloisters, nine cottages, a chapel, seven acres of vineyards and arable lands and meadows.”

The author illustrates how over a 200-year period – the 1700s to the 1800s – the Garden’s orchards and vineyards disappeared beneath streets and houses.

Jewellery for sale in a mid-20th century Hatton Garden

From the start of the 1800s, the precious stones business got a foothold.

“In the directory for 1807, there were 11 entries for those engaged in the trade,” says Vivian.

Then came the boom. By 1897, it had reached 236.

“There was never a single day when a decision was made to make the Garden a jewellery quarter,” adds Vivian. “It was through mutual needs that trades congregated in the same areas as one another.

“The advantage of working in a close community was networking could only be achieved by having a physical presence.

“Secondly, there was also a parochial supply and distribution chain compared to the market place now.”

The Second World War saw the Garden both damaged by the Blitz, and providing a haven.

One such tragic story is that of Will Trenner, an Antwerp furrier.

As the war loomed, he and a friend, a diamond merchant, knew they should escape.

“Tickets were like gold dust,” recalls Vivian. “They could only get one between them. It was agreed Willy should go first, but for peace of mind he took the stock of diamonds belonging to his friend. It would be safer for the friend to escape later without the diamonds if the Nazis caught up with him.”

Willy left – and the following day, his friend was arrested by the Gestapo. He was never seen again.

Willy spent years unsuccessfully trying to trace him, and return the diamonds.

Vivian’s research is comprehensive. He has brought alive the minutiae of a neighbourhood, the tragedies and successes, and how it became synonymous with the craft Vivian’s family are a crucial part of.

“If we could turn back the clock, we would see a very different place in each of the many generations,” he writes.

“Those who remember the Garden in the 1950s and 1960s do so with mixed feelings. Although no one choose to go back to the smoke-filled streets and the primitive facilities, there is a sense of loss for the people who were part of this thriving community.”

• How Did Our Garden Grow? The History of Hatton Garden. By Vivian Watson. The History Press, £40