‘It takes a particular skill to be in the middle of a riot and take a good picture’

David Hoffman’s images of ordinary people taking to the streets in protest have now been collected in a new book. Dan Carrier learns about life before the phone camera

Friday, 8th August 2025 — By Dan Carrier

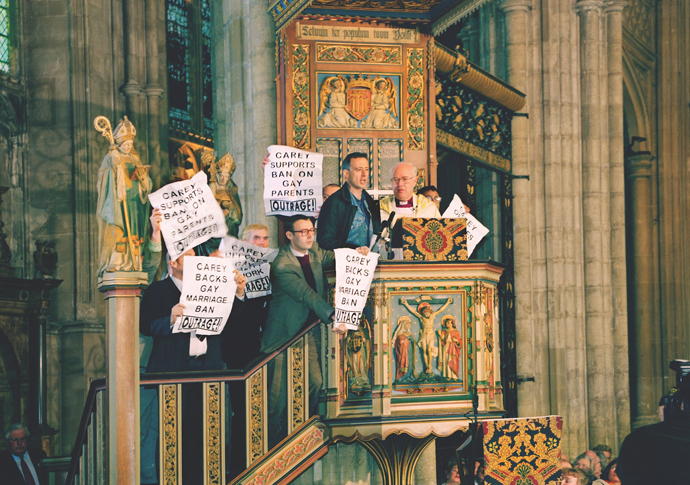

David Hoffman’s shot of Outrage disrupting the Archbishop Of Canterbury’s Easter Sunday Sermon [All images: David Hoffman Photo Library]

IT is a mixture of extraordinary front-row scenes of the past 50 years of radical protest in London, and a chronicle of the personal battle scars that photographer David Hoffman has notched up recording it.

David has been in the middle of some of the seminal moments in contemporary British protest – from the streets of Brixton in 1981 and Broadwater Farm in 1985, the poll tax riots through to the Occupy movement. Wielding a trusty camera, he has forged a career in capturing how we show our displeasure, how we support a campaign, and how the state reacts when people take to the streets.

Now a new book reveals a life spent bearing witness. Culled from a library of over 80,000 images, it’s a testimony to our right to protest.

His work begins with the eviction of squatters from the East End in the early 1970s.

David says he didn’t set out to photograph protests. Instead he had turned his camera towards the circumstances he found himself in.

He had become part of a squatting movement, a reaction to unaffordable housing and the swathes of slums that made up London’s streets.

“I was young and perhaps believed documenting these issues might help change things,” he explains.

His lens captured issues around housing, poverty and racism, and found editors at Time Out, New Society and Housing Today were interested in publishing them.

He recalls how a market for protest photographs was ramped up from 1979 onwards. It wasn’t just the circumstances Thatcherism created and the reaction to policies such as anti-Trade Union laws that meant there were more protests to cover. Capturing civil conflict became something the establishment press were hungry for.

“It fitted the media narrative that the country needed a strong government,” he writes.

“Ironically, the Thatcher years saw the highest demand for images of unrest.”

The photographs often revealed police brutality and were used in court cases. It made photographers a target – and throughout his career, David has been beaten up and arrested on numerous occasions. He recalls being targeted by the Met’s Forward Intelligence Team and the subject of surveillance.

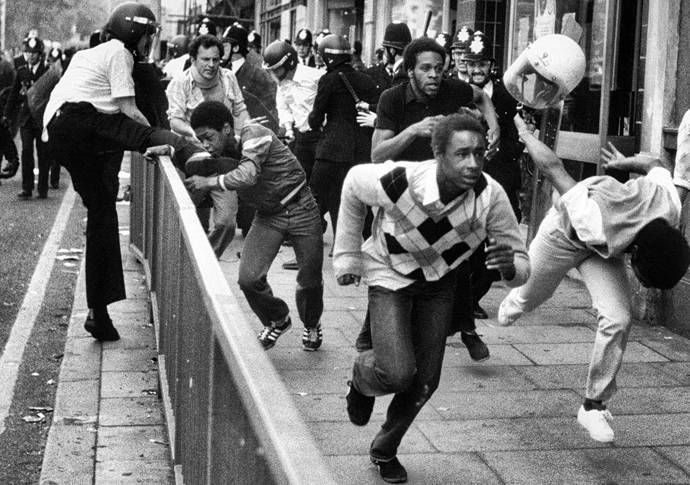

The Brixton Riots of 1981

“In the 1980s, there was police brutality and obstruction, attacks on photographers and reporters – but it felt less organised. The police would just shove you about, stand in front of you. Then they started doing more aggressive surveillance and by the end of the last century, it was ramped up and they saw press photographers as the enemy,” he adds.

“It wasn’t just because the photographers could see what the police were doing. We had good contacts with campaign organisations to find out what was going. The police might have been seen as part of the demonstrators, not members of the press, bearing witness.”

Much of his work pre-dates the camera phone, and provides documentary evidence.

“One of the reasons I went to so many demonstrations in the 1980s and 1990s was if I hadn’t been there, there would have been no record at all,” he recalls.

“We were there to bear witness as press photographers . Today, there are thousands of photographs taken at protests and someone will get lucky with a shot.”

But as David learned on the job – and it cost him cracks to the head and many a bloodied shin – recording protest requires calmness among chaos.

“It takes a particular skill to be in the middle of a riot and take a good picture,” he says.

“I would say – always know where your exit is, and then always know where your second exit is. Know where your colleagues are, and keep an eye out for each other.”

He and other freelancers created an intelligence network that shared information over where the next protest – anything from civil rights, green groups or strikes – would take place next.

“Every week Time Out printed an ‘Agitprop’ list with all the demonstrations taking place,” he says.

“You’d arrive early and stay late. Then you’d have to rush off and process your film – and then jump on a bicycle and pedal down to Fleet Street to catch the newspapers for the following day, and sell your pictures before it was too late for their print deadlines.

“Often you’d be working outside in a grey day, poor light, and so you’d want to use a slow shutter speed and the lens wide open – but trying to get a strong shot this way while chaos unfolds – it was hard work.”

The first civil unrest he covered was the 1981 Brixton riots.

Reclaim The Streets and Liverpool dockers march For social justice

“I had no idea what I was doing,” he recalls. “It was the first time I had seen real violence. It was a case of hearing a noise and running towards it.

“The violent reaction of the police was no surprise to me. I’d seen the police as an oppressive force when I was a student. I had long hair and I wore flares and I was used to being stopped and searched or harassed by officers.”

Watching the police break the law became a regular happening – and David has witnessed how the so-called forces of law and order do not stick to the rules when dealing with protesters.

“Protests do help you confirm your beliefs,” he says. “And the state really does try to stop people from expressing themselves.”

By the end of the 1990s, the police were clearly targeting photographers and David was known to the Met.

“Around this time, we noticed the police photographing us,” he recalls. The Met formed the Forward Intelligence Team, a surveillance unit that collected “evidence” on activists.

“To our surprise, they targeted us instead,” he says.

This wasn’t just taking pictures of photographers but being aggressive and hostile – shoving cameras inches away from their faces and using intimidating tactics.

“By the early 2000s, the FIT’s fixation on us was bordering on the absurd,” he says. “Sullen police officers would photograph me from just a few feet away.”

Helped by the NUJ, they discovered files labelling David and other photographers as “domestic extremists”.

David says our civil liberties and right to political expression have been whittled away by successive governments, likening the situation to the frog being boiled alive but not noticing the gradual increase in heat.

“Look at what is going on today,” he says. “Our freedom to speak out is dangerously eroded. I cannot believe the way the UK is going. It might be what you’d expect under a very right-wing government who just want to stop protests, break up groups, intimidate people – but under a Labour administration?

“Do you know that less than three per cent of arrests made at protests lead to charges, and even less to convictions?

“Now they are trying to police what you have on a T-shirt, on a banner. And there are many ways the police seek to incite people so they have an excuse to break up the right to peaceful protest. I am frankly amazed at how bad it is.”

• Protest. By David Hoffman, Image and Reality Books, £40 hardback; £28 softback