‘If you had a gun you were seen as more left-wing’

Dan Carrier talks to John Foot about his latest book, which details the 18-year history of Italy’s Red Brigades

Friday, 18th July 2025 — By Dan Carrier

John Foot, author of The Red Brigades

IT was a crime that stunned Italy. In a society that had witnessed political, Mafioso and vendetta violence, the murder of five bodyguards of the politician Aldo Moro in broad daylight in the centre of Rome was shocking.

Moro spent 55 days as a hostage before his bloodied corpse was found in the back of a Renault 4.

The Moro tragedy is a sorry chapter in the story of the anti-capitalist Red Brigades.

In a new book detailing the 18 years that saw the terror group wage war against the state, John Foot takes the reader through the reasons the Brigades was formed, their tactics and aims, perceived successes and failures – and the stories behind the violence they unleashed.

“I have always been fascinated by the Red Brigades,” explains the historian, who has previously covered a range of topics including Italian football and cycling. He lived for many years in Italy and the Brigades had long held a fascination.

“I was once at a book launch in Milan in the 1990s and found myself sitting behind two of the leaders,” he recalls.

“They were just two old guys. The people involved are still around. The archives were extensive and full of crazy stuff – everything from letters and posters through to false ID cards.

“In one envelope, a collection of bullets fell out. The evidence was amazing.”

The Brigades have long been a cause of fascination: their urban guerilla war created a period that would become known as The Years Of Lead. Political violence became commonplace – in 1979 alone, the police recorded 2, 514 terror incidents.

John describes the landscape that formed them, what they intended to achieve and the violent methods they used.

Moro’s kidnapping rocked Italy. He had been prime minister and was a senior figure in the Christian Democrats.

“He was an obvious target,” explains John. “Nearly every morning he went to the same church. His two-car convoy often took a well-known route. Neither car was reinforced and his guards, though armed, kept some of their weapons in bags of the glove compartment.”

On March 16, 1978, this routine would lead to death. An armed BR unit based in Rome attacked Moro’s cavalcade: four brigatisti terrorists murdered Moro’s driver and bodyguards. They bundled Moro away and held him hostage as frantic attempts were made to find the Brigades’ base. Demands were made for the release of brigaders held in prison: the saga ended with the discovery of Moro’s bullet-riddled body.

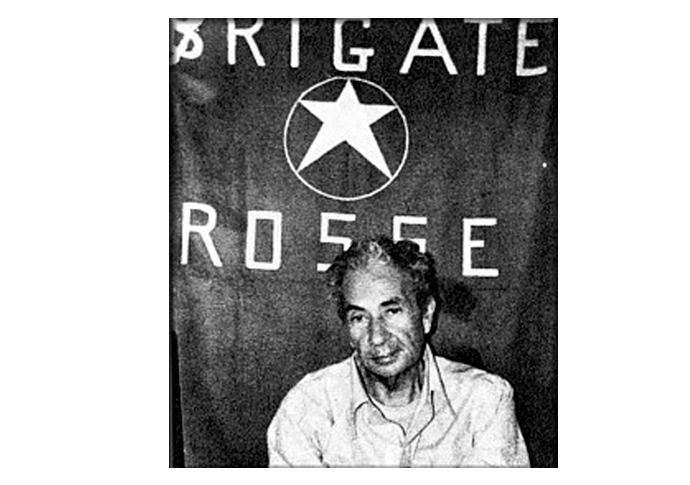

Aldo Moro during his detention

“They were probably the most important left-wing group in Europe, along with the Baader Meinhof faction,” reflects John.

The Brigades came from a period of revolutionary fervour, spurred on by a sense of inheritance from Second World War anti-fascist partisans.

“In the late-60s you had a huge student movement – far bigger than the UK and even France,” he says.

“There were university occupations in 1967 that radicalised students nationwide. Some of the leadership came from this.

“Then there was the workers’ movement in 1969 which saw waves of enormous strikes.”

In northern Italy, sprawling industries employed thousands, creating fertile ground.

“Turin, Milan and Genoa saw class struggle,” says John. “There were workers, young communists who felt disillusioned, and students. Over the next 18 years the membership was drawn from these groups.”

For idealists, the Brigades offered a route to building a better world, and made them feel they were actively working for it.

“It became seen as quite glamorous – though it was disastrous,” adds John. “If you had a gun you were seen as more left-wing.”

The Brigades were not a mass movement – a terror group could not be due to the need for secrecy.

“It was a very small number, but they had supporters who were either ideologically in favour or at least indifferent – people knew, for example, on shop floors who were members but would not go to the police.”

Their impact is nuanced – they operated for 18 long years without the state able to stop them.

“The class struggle was violent and they acted against those they felt were legitimate targets – for example, factory supervisors,” he says.

Armed partisans had fought Italian fascists and German Nazis and many felt their work was betrayed in the post-war period as Italy saw American money flood into the economy, big businesses thrive off the back of the workers’ toil, and many members of the war-time fascist regime avoid censure.

“They saw themselves as being the new partisans,” he says. “They were worried about the emergence of the far right and the possibility of a coup. They thought they were continuing the resistance, defending the working class against a right-wing surge

“They felt that was a justification. In the early days, Brigades were given guns by partisans who said ‘we did not finish the revolution’. In many ways, that was just bonkers.

“Italy was a democracy with a constitution, but they dubbed it a fascist state.”

The flag of the Red Brigades

The Brigaders were inspired by the war generation – but also global left-wing movements. Che Guevara and the Cuban revolutionaries were poster boys, as was Brazilian revolutionary Carlos Marighella, who wrote a manual on urban guerilla war. They read the works of Marx and Mao.

But the idealism that drove them was also detached from reality, adds John.

“They lived in their own world,” he adds. “They were ideological – they believed in ‘people’s justice’ and they said they spoke for the whole of the proletariat.”

The response of the Italian state was disjointed. Trials were constantly delayed: there were problems with selecting juries, threats to magistrates. Brigade lawyers challenged the legality of the proceedings and prisoners did all they could to avoid complying.

“The state was all over the place,” says John.

“In the end they expanded the possible jury pool to 100,000 so they could find 10 people to sit. It is extraordinary to think a group of around 30 people at any time could hold the state to ransom.”

And what did the Moro tragedy do for the Brigades?

“Many were repelled,” writes John. “But others were impressed and excited by this show of force.”

It added to their global fame, with the Brigades featuring the covers of Newsweek and Time. But the murder did not change the political landscape.

And Moro was a point of no return for how the authorities treated terror suspects: a secret squad now used torture to glean information.

A few months later, the Brigade struck again – this time killing a left-wing trade unionist, Guido Rossa, who was gunned down in his car.

The image of this working-class activist who had the gall to speak out against Brigade violence sucked away support.

A kidnapping of Nato’s Brigadier General James Dozier in 1981 – the US soldier was rescued – led to multiple arrests, leaving only a handful of Brigaders at large.

The final act came in 1988 with the murder of senator Roberto Ruffilli. The perpetrators were caught and the Brigades were no more.

“Many made excuses for the Brigades,” says John. “They were manipulated, they were puppets, they were the creation of Mossad, the CIA, the KGB, riddled with spies and agent provocateurs. They prompted a host of repressive laws.

“Many felt they were allowed to act to besmirch the left – which it did. For everyone, it was a disaster.”

• The Red Brigades: The Terrorists Who Brought Italy to its Knees. By John Foot. Bloomsbury, £25