Iconic Isokon

The Isokon Building in Lawn Road has just turned 90. Dan Carrier pays a timely tribute to its designer, Wells Coates

Thursday, 15th August 2024 — By Dan Carrier

The Isokon Building in Lawn Road

THEY were the bane of the flapper generation: as Britain emerged from the Great War, Modernism gripped a generation.

Those who had seen their older brothers sent to their deaths in the trenches rejected the world that had led to the mass slaughter, and dismissed the stuffy Edwardian values that they associated with the tragedy .

But for the modern man and woman, one hated symbol of the past exerted far too much influence on their daily lives – the dreaded landlady.

And there was one industrial designer who recognised this drain on individual freedom and set about fixing it.

Designer Wells Coates joined forces with Modernists and plywood manufacturers Jack and Molly Pritchard, who owned land in Lawn Road, Belsize Park, and who commissioned Coates to build a family home.

He suggested a new form of housing block, a practical answer to a swathe of people house builders did not acknowledge, with a home for the Pritchards on the top floor.

It is 90 years last month now since the first tenants moved into his Lawn Road building – and the story of Coates’ life and the impact his designs has on Britain is writ large in the pages of a biography of the designer by Elizabeth Darling, published 12 years ago by RIBA.

She shows how by the 1990s, after a period of decline, Wells Coates’ genius was recognised and his two stand-out communal blocks – the Isokon Building flats in Lawn Road and Embassy Court in Brighton – were restored and upgraded to fit the needs of tenants today.

As Darling explains of Lawn Road: “The new block needed to be distinctively different, and better, than the emerging type of urban flat, which offered serviced accommodation invariably within a neo-Georgian exterior.

“They defined their target market as the modern professional, male or female, who more usually had to settle for ‘rooms’ in a converted house, without a private bathroom or cooking facilities but invariably with a fearsome landlady.”

Darling’s book tells the story of Coates’ life and interprets his work and its impact, and shows how he represents the Modernist movement:

“He was an architect but he was also an engineer, an industrial and product designer, a teacher, innovator and above all a visionary,” she writes.

And it was this marriage of industrial design and his background in engineering that tallied perfectly with his belief that the home should be a machine for life, a place designed to maximise ease and comfort for the needs of a post-war society.

Coates was a significant figure in British Modernism who produced some of the most interesting and important work in the interwar years – and Darling explains how it was a marriage of aesthetics and practicalities that created his unique style.

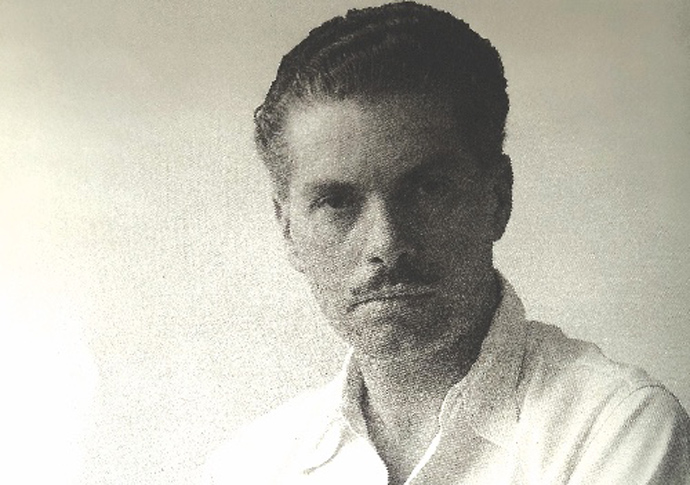

Wells Coates [Riba]

“[His] sophistication of practice owed much to his immersion in the most progressive circles in London’s art world following his arrival in the city in 1922,” she adds. Coates hung out with painters, sculptors, surrealists, ingratiating himself into the many shades of creativity found in the Bloomsbury and Fitzrovian sets.

But his journey into design was not straight forward.

Born in Japan – his parents were missionaries – he learned calligraphy and craft skills. Japanese influences – such as sliding doors as room dividers – would stay with him throughout his career.

He studied engineering for a six-year degree in Canada; it taught him draughtsmanship as well as nurtured his lifelong interest on how things work.

It was a sign of his interest in modernity that after serving in the Canadian Field Artillery – his job was to look after the horses that dragged the guns to the front – he enrolled in the Royal Flying Corps. He completed his training as the war ended.

Wells Coates finished his engineering degree but his life went in an unforeseen direction when he found a part-time reporter’s role at the Daily Express.

At the same time, he became friends with Alfred Borgeard, with whom he became the archetypal modern intellectual: the pair read Modernist literature, delved into philosophy and flirted with communism.

He became a figure in Soho and Fitzrovia circles, living in Fitzroy Street where his neighbours included Vanessa Bell, Paul Nash and dancer Frederick Ashton.

He met and fell in love with LSE student Marion Grove and when they decided to marry, he converted his Doughty Street bedsit, using materials – aluminium and plywood – that he had handled when flying the Sopwith Camel biplane during his air force days.

A commission to design interiors for Labour MP George Russell Strauss followed, as did a larger job fitting out the interiors of shops for a silk manufacturer.

“I am a trained engineer,” he would say. ‘“And I believe housebuilding today is the business of the engineer plus the painter.”

Pritchard was impressed by Wells Coates’ use of the material in his shop designs. Another self-proclaimed Modernist, they shared interests and they formed a partnership to change the way house building was done.

Lawn Road, with its serviced flats, attracted a mix of London’s progressive set – Agatha Christie had a flat and was said to base characters on the people she met at Lawn Road – while it also attracted emigres who had fled Nazi Germany.

The plan was that profits made from the homes would fund another block and so on, but the hoped-for profits never materialised.

Wells Coates went on to design other homes and factories, and a pavilion at the Festival of Britain.

But it was another stint in the forces that again inspired him: called up in 1939 due to his work as an RAF reservist, he was sent to Bristol to help design the de Havilland Vampire fighter plane. His attention turned to the problems of reconstruction – and he became the guiding light in the creation of prefabs for bombed-out families.

Of the 160,000 built to provide temporary housing – which often became permanent – a third were based on a design by Wells Coates.

Despite the significance of Lawn Road, and the feted designer behind it, by the 1960s the block faced serious issues and was under threat of demolition.

The Pritchards sold it to the New Statesman magazine, who after three years doubled their investment by selling it on to Camden Council.

As part of the Council’s housing stock, it slowly declined, despite being listed in 1974.

It reached a point where it was declared “at risk” by English Heritage. In 1999 it became Grade-I listed and in 2001 the Notting Hill Housing Trust took it on.

Today, the block stands as a testament to the far-sighted work of a designer who poured his philosophy of opportunity and freedom for all into the foundations of the projects he turned his draughtsman’s eye towards.

• Wells Coates. By Elizabeth Darling, RIBA publishing, £9.99