Heightened census: a window into life 100 years ago

The publication of the 1921 census sends Dan Carrier down a few historical rabbit holes...

Thursday, 20th January 2022 — By Dan Carrier

Street scenes, here and below, from the decade the census was taken. Photogravures by Donald Macleish from Wonderful London edited by John Adcock, 1927

THE Austen family ran a furniture shop from what is now the front desk of the New Journal’s Camden Town headquarters.

It was June 1921, and Elizabeth Austen, a widow, earned a living kitting out Camden Town’s kitchens and parlours.

On a summer night 100 years ago she sat at a table – perhaps one she hoped to sell from our reception area – and filled out a census form.

Across the UK that evening, 37 million other people were doing the same thing – and now, a century on, the results have been made public.

The 1921 census, now available online, offers a unique window into the lives of the Britons who have been born, have lived, loved, worked and died in the houses we occupy today. It offers the chance for everyone to explore their family history.

For members of the Society of Genealogists, based in Holloway Road, this swathe of newly released information is a treasure trove.

The Society’s chief executive, Dr Wanda Wyporska, told Review how its publication is eagerly anticipated by both the professional and amateur historian.

“Many think of genealogy as posh people in search of their royal pedigrees, but in reality, our members are people from all walks of life, passionate about finding out their family histories,” she says.

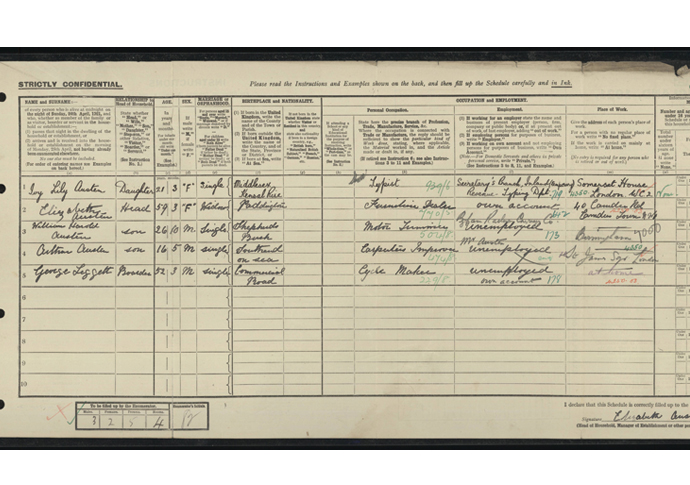

We know from Elizabeth’s handwritten return that she lived with her sons, William, 26, and Arthur, 16. Both were out of work, describing their trades as “motor trimmer” and “carpet improver”.

Lodger George Leggett, 52, also unemployed, says he is a “cycle maker”. Daughter, Ivy, 21, has a temporary job as a typist for the Inland Revenue at Somerset House.

“The schedules were completed by the householder so we can see their handwriting, for good or bad,” adds Wanda.

“As housing was an issue after the war, this census asks how many rooms the family lived in – an indication of economic status.

“The census also shows people in prisons, hospitals and other institutions. It is particularly useful for discovering the industries and companies your ancestors worked in.”

The returns for the borough of St Pancras show men were mainly employed in transport or communications – no doubt due to the proximity of railways and canals. Others, in more well-heeled streets, were involved in commerce and finance.

The 1921 census entry for Elizabeth Austen, ‘furniture dealer’, and the other inhabitants of 40 Camden Road – headquarters of the New Journal

And with Camden the home to the UK piano trade, and the Bedford Music Hall in Camden High Street just one of a number of such venues, many said their trade was as “entertainers”.

The majority of St Pancras women worked in domestic service – a job also done by a considerable number of men. One trade with gender parity was clerks and draughtsmen.

“As a result of the number of men killed or left permanently disabled, the 1921 census shows many more women stepping into employment, with an increase in the number working as engineers, vets, barristers, architects and solicitors, though the largest employment sector for women was still domestic service,” says Wanda.

And the impact of the Great War is laid bare in other ways, adds Wanda.

“The census reveals there were 1,096 women for every 1,000 men, this discrepancy being the biggest between 20 and 45,” she says.

“There were over 1.7 million more women than men, the largest difference ever seen in a census.”

And the figures also reveal the personal tragedies: more than 730,000 children had lost a father, while there is a 35 per cent increase in people in hospital, three quarters of them men recovering from war wounds.

The survey was managed by the government’s General Register Office, based in The Strand. They took on hundreds of part-time staff for the job, delivering and collecting the forms.

Using an early type of mechanical computer, punch cards were created with information filled in by a team made up of young, single women – chosen as their supposedly nimble fingers were considered well suited to the task. By the time it was completed, they had filled in details for 37,886,699 people.

This year’s publication has extra resonance, as it will be the last published until 2052. The 1931 census was destroyed in a fire, and due to the Second World War, no census was completed in 1941.

Dr Wanda Wyporska

For Wanda, who has roots in West Africa and Barbados, the census is another tool she can use to trace her ancestry.

“I was thrilled to find a great-great-grandfather who was born in Bristol, but lived on Hampstead Road for a while, and my gran lived in Tufnell Park. Although I’ve lived in north London for decades, I was born in Chester, so it was fantastic to find older connections with Camden.

“I’m spoilt for choice, with English, Polish, and Bajan lines of family to explore.”

The Society’s archives include parish records, family histories, apprenticeship lists, poor law records, huge rolls with family pedigrees stretching back centuries, and school records. Added to the census, they provide a formidable tools for those who want to discover more about their past.

“We have records from the former British colonies, including indentures, business and industrial records that allow many of us to trace our family’s journeys through enslavement,” adds Wanda.

“I am keen for SoG to work with communities and groups to explore their histories, because as Maya Angelou said: ‘If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.’”

The Society can guide you if you want to discover more about your past, she adds.

“The first thing to do is to get a big notebook,” advises Wanda.

“Talk to your family – ask older members about what they remember, ask them about the stories they heard, ask them about journeys, travel, rumours, locations. Get as much information as you can, and then go from there.

“Family research is history personalised for you. Once you explore it, your life is never your own again.

“People are curious – they want to know about their family. These records can either confirm what they knew, or throw up new mysteries. It is detective work.”

• For more information about The Society of Genealogists: tel: 020 7251 8799, email: hello@sog.org.uk website: www.sog.org.uk