Hazlitt: the original blogger

Never one to stay his quill, the 19th-century commentator William Hazlitt is as relevant today as ever, writes Dan Carrier

Thursday, 19th September 2019 — By Dan Carrier

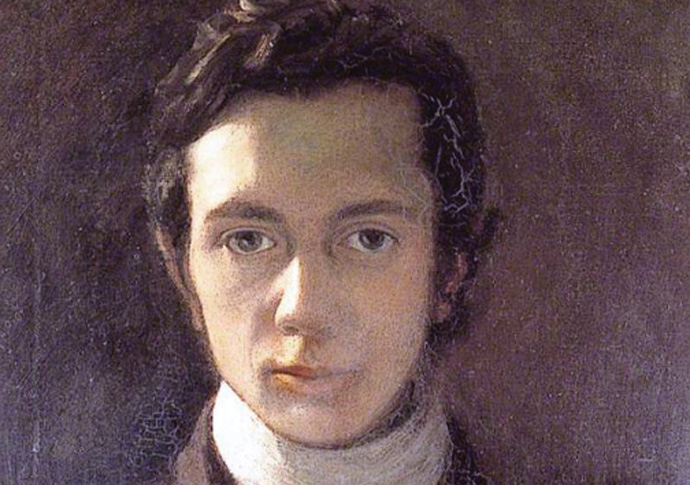

William Hazlitt’s self-portrait of 1802

HE stalked the clubs and pubs of Soho, skulked through the corridors at Westminster, and listened intently at the debating houses, the law courts and political societies of Georgian London.

And William Hazlitt – writer, commentator and journalist – turned his swift and vicious quill towards anyone and anything he thought worthy of attention.

The wordsmith strode through his age as a literary colossus, earning friends and enemies in equal measure: and his writings on politics ring down through the ages like missiles of truth.

Last weekend The Hazlitt Society – based at University College London in Bloomsbury – hosted its annual Hazlitt Day School to celebrate the journalist, who died in a Frith Street boarding house in 1830. The speakers included former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger, presenting a paper on Hazlitt, The Guardian and the Peterloo massacre, and a host of academics who champion the freethinker’s work.

Hazlitt Society chairman Dr James Whitehead teaches the works of Hazlitt and other literary figures of the Romantic Period – and says Hazlitt’s ideas have not been diminished by the passage of time.

“It has been the case that the Romantic Period is identified with the “Big Six” poets – Wordsworth, Shelley, Blake, Keats, Coleridge and Byron – but not their politics,” he states.

“This happened with Percy Shelley in the 19th century – he had to stop being identified as an atheist and revolutionary before he could accepted as a poet.”

While Hazlitt was one of the key figures in a period of monumental change where the French Revolution spread hope across Europe, his insightful work has often been deliberately overlooked as he spoke truth to power.

It didn’t start out this way for the Maidstone-born writer, says Dr Whitehead. “Early in life, Hazlitt was a very good painter,” he says.

“His brother had been a successful miniaturist and by what we have seen from his surviving paintings, he was easily good enough to make it as a painter too – but he was a perfectionist and believed others were better than him. His heart lay in being a political writer. He produced work for journals and periodicals – but this type of writing was seen as disposable. It meant he was somewhat overlooked. There was this sense that only the poets could achieve immortality through their work.”

In 2002, a campaign led by the late Michael Foot sought to raise funds to restore his grave in St Anne’s Churchyard, Soho – and led to the establishment of the Hazlitt Society.

“Many political figures, stalwarts of the British left, became involved with the Hazlitt Society,” adds Dr Whitehead.

And his polemics were printed in an era that saw such public discourse blossom.

“Hazlitt came when there was a new media environment,” says Dr Whitehead.

“There was an increasingly educated public. There was industrial printing techniques. There was a huge outpouring in print, and public spats between figures – very much like the internet today. It was like Twitter, in a way, and Hazlitt was like the first blogger. Like today, this new media encouraged a sense of partisanship, of fractiousness in writing. There were rows in print that ended up in duels.

And Hazlitt was not averse to cutting people down. His book Political Essays with Sketches of Public Characters, printed 200 years ago, was a collection that took aim at the hypocrites in public life. Even while he had at first been friendly with the Romantics, he was not in thrall to their reputations.

“Hazlitt did not always agree with those he had been friends with,” adds Dr Whitehead. “He fell out with Wordsworth and Coleridge. He was there when they were on the left and supported the revolution but as they drifted rightwards, he really went for them. He savagely reviewed Coleridge’s later writings and held them to account for their political shift.”

Above all, his writings still have power today as they attack the foundations of much that is wrong now with British society.

“He believed in liberty, equality and fraternity,” adds Dr Whitehead.“He was a democrat, he called for Parliamentary reform. He was ferociously Republican and fought the idea of the divine right of kings. His work On The Spirit of the Monarchy should be read whenever there is a royal wedding.”

The piece lays bare the ridiculous nature of inherited power, and demolishes the monarchy with its cost, its pomp and traditions that entrenches power and symbolises inequality.

“He was such a tremendous slayer of hypocrites and there were some real bastards about, some really tyrannical figures,” adds Dr Whitehead. “He would study an argument from all angles and then go in with his idea: he was concerned with how power corrupts. Above all, he was interested in how to create a better society and saw it as his work to do so.”

• See www.ucl.ac.uk/hazlitt-society