Stevie Hyper D: Urban legend of 1990s jungle

New documentary charts the meteoric rise, and tragic fall, of iconic MC

Friday, 1st November 2024 — By John Gulliver

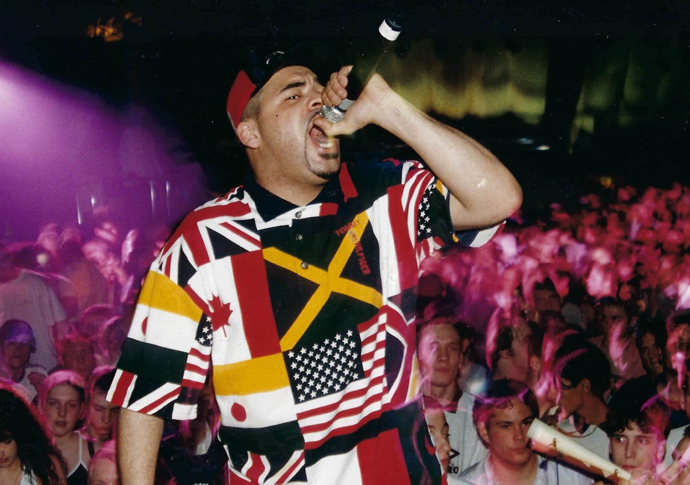

Stevie Hyper D had ‘complete control of the crowd’ [Triston O’Neill]

WATCH OUR POLITICS CHANNEL ‘PEEPS’ ON YOUTUBE

I THINK the closest brush I’ve had to a religious awakening, barring Arsenal of course, is mid-1990s’ jungle/drum and bass.

There was a time when I was obsessively devoted to this uniquely British music, knowing not just the names of the tracks but the niche detail of every break.

In this pre-internet era, when the things you wanted weren’t immediately obtainable at the touch of a button, weekends would be spent hopping about the many secondhand record shops.

I’d be hoping to find a recycled gem, but most often arrived home to find it wasn’t quite the one you had heard on pirate radio, or the many mixtapes that were typically passed-down from above, with an almost spiritual aura, by someone’s older brother or uncle, or in the years above at school.

There were record shops all over the place, Camden Town, Angel, the West End, Notting Hill – and I remember first getting to know how London areas linked-up together while trawling for vinyl.

But the true mecca for all “junglists” was Blackmarket Records in D’Arblay Street, Soho.

A somewhat intimidating place for a skinny schoolboy, I remember it thick with smoke, ear-splitting sound, and a battle-hardened older crowd brimming with attitude.

Here you could buy the latest tracks as they came out, cassette tape-packs – a kind of box set of the day – flyers, slip-mats and record bags. And crucially you’d pick up your tickets for the raves.

Darrell Austin

“I’d be lying if I said I didn’t miss the shop,” former owner the DJ Nicky Blackmarket – still to this day packing out massive arenas – told me this week. “It was part of my life for 20 years. But things move on.”

For many people into this scene in the mid-1990s the number-one draw was Steve Austin, aka Stevie Hyper D.

A new documentary – released this month by Dartmouth Films and playing in Odeon cinemas – charts the meteoric rise, and tragic fall, of this iconic MC, who died from a heart attack aged 31 in the Royal Free Hospital in 1998 after a rave at the old Camden Palace, now Koko, in Camden High Street.

It doubles as a raw and joyfully nostalgic love letter to the 1990s, bringing back to life an urban legend celebrated for his live performances.

“He was an all rounder,” said Nicky, a close friend who played countless nights alongside him around the country. “He could mix it up, all styles. That’s why people loved him. He had an energy about him.

“When we started to go on the road together, it was like some soul friend kind of thing.”

DJ Nicky Blackmarket

The film tells how Hyper D, from west London, had shortly before his death signed a contract with Island Records and was on the cusp of breaking into the mainstream.

Lovingly told through the lens of his nephew Darrell Austin, determined to ensure his uncle’s legacy is not forgotten, it features all the main players from the scene.

Brought up in Fulham with roots in Barbados and Spain, he was inspired by black artists he saw on Top of the Pops, the likes of Rebel MC, Tippa Irie and Smiley Culture.

He showed “all the signs of ADHD” growing up, but this was “overlooked” with him regarded simply as “an overactive child,” says Darrell, who remembers how he “spent time in prison for knocking out a bus conductor for calling him a ‘wog’”.

The story tells how his Hyper D act came to the fore when rave music shifted around 1994 from a “happy white glove wearing scene to a darker vibe”, with nights at Telepathy and Thunder and Joy, just off Tottenham Court Road, where crack smoke hung in the air and people were getting mugged in the toilets.

Darrell said: “At that time you had to know how to carry yourself, you had to have a bit of streetwise about you.”

Steve Austin, aka Stevie Hyper D [Triston O’Neill]

As a boy, Stephen had hung out with a group called the Cubs, along with the son of the black rights activist Darcus Howe, Darcus Beese, who went on to become president and chief executive of Island Records. Darcus recalled seeing his childhood friend after years apart performing in a basement room of a rave.

“I’m getting goosebumps even thinking about it now,” he said. “He had complete control of the crowd. He had his own fans, he had his own lyrics, he had done it all with his own graft. The logical thing was to see if he wanted a record deal.”

He was there at the Free when Hyper died. “His last words were ‘sorry’. It knocked me sideways, to lose a friend.”

The Different Levels album was more than a year in production when Hyper died.

It was finished posthumously by his peers on the scene and played repeatedly at a memorial rave in Camden Palace in 1998.

Tiana, Hyper D’s daughter, said: “I still have people come up to me in the street and they get so emotional. You wouldn’t think jungle would bring this out in people.

“But I feel that he had this energy that would really translate into a room, and lift a room. Everybody that listened to the music then still listen to it now. It’s amazing, and I’m very proud.”

The Stevie Hyper D Story, distributed by Dartmouth Films, is on at Odeon cinemas from November 19.