Harrington: Mars stars

UCL professor seeks to answer the big question over the red planet

Friday, 16th June 2023

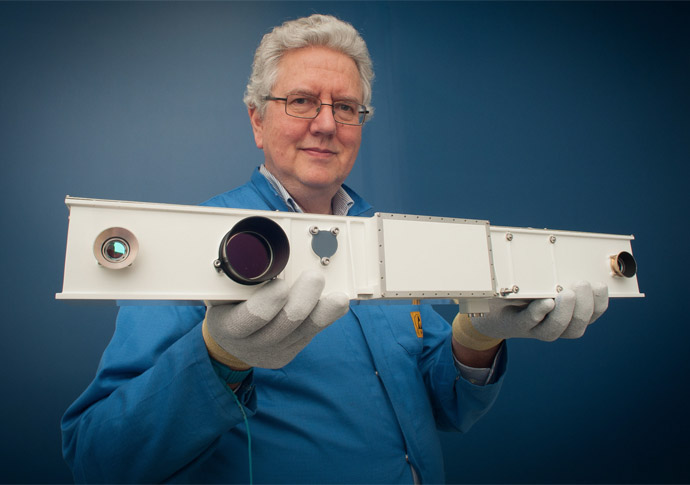

Andrew Coates holding the engineering model of the PanCam instrument for the Rosalind Franklin (ExoMars) rover [Photo: M. de la Nougerede, UCL/MSSl]

THEY say one of the tricks to life is finding a job that you enjoy, so it doesn’t feel like work.

Physics professor Andrew Coates over at UCL seems to have taken this approach, clearly enraptured as he is with a quest to finally answer the eternal question: Is there life on Mars?

“We’ve been working on this mission for 20 years,” he explained to me this week, talking about plans to send the pioneering Rosalind Franklin rover to the red planet in 2030. “It makes us get up in the morning. This is the best job in the world.”

Professor Coates is the principal investigator of the PanCam – the eyes of the rover. That’s not a spirit level he’s whipped out of the garden shed in the main picture.

He’s previously been involved in uncrewed missions to solar system objects, including Halley’s Comet and Jupiter’s moons.

“In 10 years we’ll probably know the answer to whether there was ever a life on Mars or not,” he said, adding that, looking even further on in the exploration, Mars is the “best chance” for finding life in our solar system due to its history of water on the planet.

“You need four things for life: water, the right chemistry, time for life to develop and a source of energy to keep it warm,” he said.

I’ll be honest if I had spent two decades on the project with another seven years to go, I’d be hoping to meet a Martian – maybe even find Matt Damon up there, still growing potatoes.

But there will be no green-skinned aliens at the end of the mission.

Professor Coates is hopeful they will find biomarkers that indicate primitive forms of life once lived there.

“The best thing would be if we are able to find cell fossils, cell-like life like amino acids, which are the building blocks of life, and sugars and things like that,” he said.

To do that, they’re going to have to dig deep.

“We’re drilling two metres underneath the surface because Mars has got this very thin atmosphere because of losing its magnetic field 3.8 billion years ago,” he said.

“The thin atmosphere means the surface is bathed in radiation from space. Being on the surface of Mars is a bit like being underneath the ozone hole on Earth all the time. That is not good for life.”

Certainly listening to Professor Coates enthusiastically wax lyrical at the potential of finding some amino acids 140 million miles away from home is much more fun than watching the dreary but award-winning movie, The Martian, which has become a popular reference point on how we might survive up there.

You can only wish the excited professor well.