Gone fission: the scientists with their heads in the (mushroom) clouds

A new slim volume examines the history of the science behind the atomic age. Craig Kenny looks at this tale of terror

Friday, 18th July 2025 — By Craig Kenny

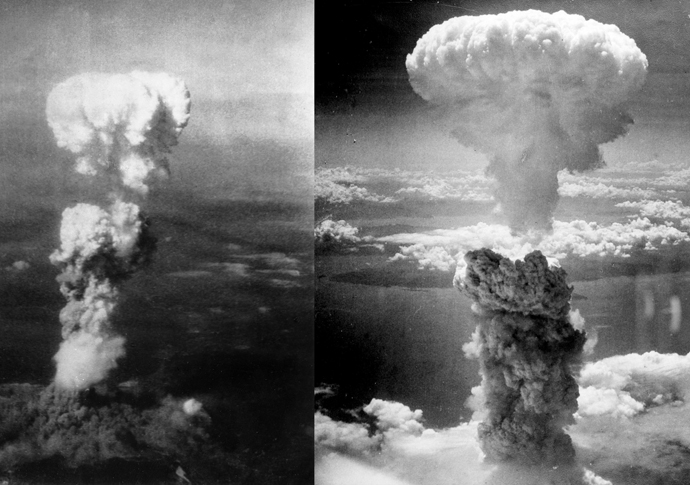

Atomic mushroom clouds over Hiroshima, left, and Nagasaki

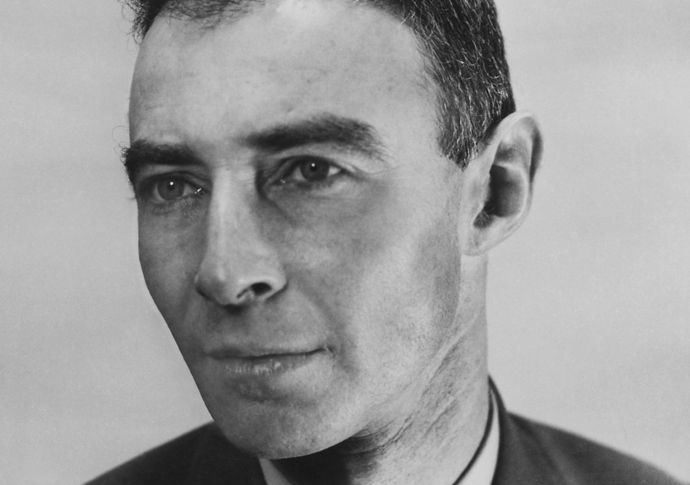

DESTROYER of Worlds opens with a vivid description of the first atom bomb test at Los Alamos, a scene depicted cinematically in the recent movie Oppenheimer.

In a slim volume aimed at the general reader, Professor Frank Close recounts the history of the science that underpins the atomic age. The title is a quotation from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

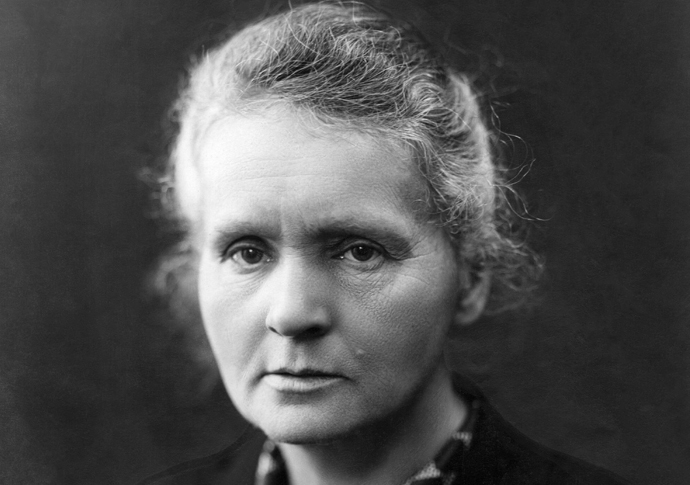

Close describes the early – often hazardous – experiments: Rontgen’s discovery of X-rays is elegantly told like a Gothic horror tale; Marie Curie’s isolation of two new “radioactive” elements also exposed her to their deadly rays. JJ Thomson’s demonstration of cathode rays yielded up the secret of electricity-electrons. It’s an experiment that I have often replicated in the physics classroom.

A major challenge for these early researchers was the elusive nature of radioactive elements. They kept transforming into other ones. Curie’s radioactive materials were found to emit two other types of rays, christened alpha and beta by Ernest Rutherford. He was the first scientist to realise the vast amount of energy carried by these rays, far exceeding what chemists were used to. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t Einstein, but the writer HG Wells who first conceived the notion of an “atomic bomb”, we are told.

Rutherford’s subsequent discovery of the atomic nucleus was a turning point.

Marie Curie

We follow every twist and turn of this complex detective story, as nature gradually gave up its secrets: protons, neutrons, photons, neutrinos, and even antimatter were added to the particle zoo. Meanwhile, in the background, the First World War was raging. Revolutions ignited,both political and intellectual. Quantum theory was devised to govern this new particle domain.

Next came the “atom smasher” machine which deployed high voltages to break up lithium atoms. Rutherford and his colleagues had “split the atom”. But he dismissed as “moonshine” the idea that this might be a useful source of power. One physicist thought that it might be done though – Leo Szilard dreamed up the idea of a nuclear chain reaction while crossing a road in Bloomsbury.

The author reminds us that the scientists in this story were also human beings, as prone to jealous rivalries as to brilliant insights. Aside from accounts of misogyny and anti-semitism, we learn of the mysterious disappearance of Ettore Majorana, who was called a “magician” by his peers. Did he anticipate the development of the atom bomb and commit suicide in 1938, leaving no trace?

Curie excepted, the contribution of female atomic scientists is too often ignored and Close remedies this neglect.We learn how Curie’s daughter Irene and her husband created the first artificial radioactive isotopes.

Next Lise Meitner enters the story. Forced to wear a yellow star under Nazi race laws, she abandoned her work bombarding uranium with neutrons.

While fleeing to Sweden, Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch calculated how much energy could be obtained by splitting a uranium nucleus in half. After their predictions were confirmed in the lab by Niels Bohr, all three set sail for New York, where news of the discovery had already arrived by wire .And so the secret of nuclear fission was brought to the Allied powers by Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.

Robert Oppenheimer

Further experiments revealed that a rare isotope of Uranium 235 was the ideal candidate for setting off a nuclear chain reaction, so the natural substance would require enrichment. The same day that this insight was published, Germany invaded Poland and the Second World War broke out.

After that, the race was on. Einstein wrote his famous letter to FD Roosevelt. The French made heavy water and hid it from the invading Germans. A veil of secrecy descended. Information once freely shared among scientists became classified. But the discoveries continued. They made artificial elements like plutonium, which proved a better choice than uranium for a fission bomb. They also learned how to control the chain reaction,which was essential for the peaceful exploitation of nuclear power.

One chapter briskly tells how the Manhattan Project team assembled three “footballs” of plutonium – one to explode in the desert test and two to drop on Japan. Even before those bombs struck, the scientists were already plotting a far more terrible weapon – one that harnessed the greater power of nuclear fusion. To help solve the technical challenges, the team brought in an early electronic computer. Despite this, one key problem was solved by Klaus Fuchs, the spy who passed on nuclear secrets to the Soviets, and is the subject of another book by Close.

Soon, the Americans, Russians and British were all testing their own H-bombs. Peak insanity was the 50 Megaton “Tsar Bomba”… yet commercial fusion power still eludes us to this day.

The mushroom cloud that these scientists unleashed still darkens our world. We continue to see war over nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, and hear how the British servicemen who were exposed to weapons tests in the 1950s are still fighting for justice. As radiation damages genetic material too, their descendants also suffer the toxic legacy.

• Destroyer of Worlds: The Deep History of the Nuclear Age 1895-1965. By Frank Close, Allen Lane, £25