Fascism up close

David Winner finds John Foot’s history of Italian fascism a vivid, visceral, but above all relevant read

Thursday, 13th October 2022 — By David Winner

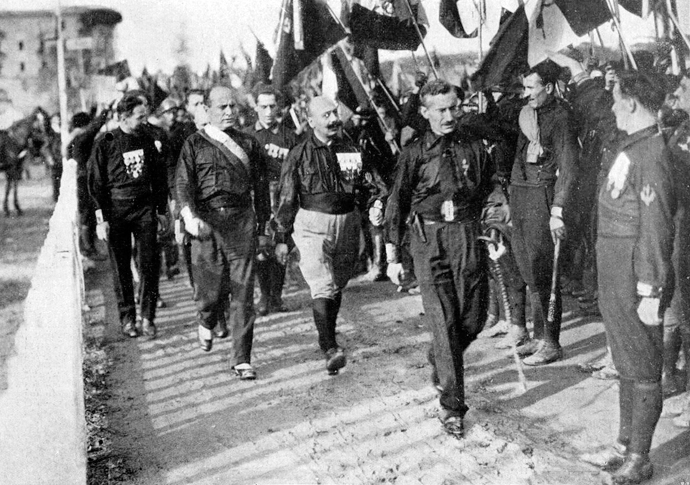

Mussolini’s march on Rome, 1922

I LIVED in Rome in the 2000s but never quite understood the essence of Italian fascism, even though signs of a potential revival were all around.

I remember being shocked to see street traders selling Mussolini posters near a tourist hotspot. (Why was this tolerated? Who bought this stuff?). When fascist posters defaced walls in my neighbourhood, local residents and authorities seemed not to mind.

Yet even though Silvio Berlusconi had brought neo-fascists into government, there was little sense of direct threat.

At the time, I read fairly widely and watched films on the Mussolini era.

But I wish John Foot had written this magnificent book sooner so I might have understood the subject better.

It’s a tremendous work: vivid, visceral, and highly relevant to our own time. As he explains, Italy invented fascism. Italian fascism inspired and informed all later versions including Hitler’s, Franco’s and the new variants currently stalking us.

Instead of dense political theory or detailed chronology, Foot gives us a history “through episodes, fragments, massacres and trials, moments of violence and escape, defeats and victories, silences and noise, rhetoric and reality”.

His approach succeeds brilliantly. We meet an extraordinary cast of characters: thugs and criminals; the complicit and those who resisted; would-be assassins; the ordinary and the extraordinary; those who stayed, those driven into exile.

Most compelling and chilling, he shows how, over just a few years, a solid-seeming liberal democracy was destroyed by systematic violence, lying and contempt for the rule of law. Parallels with our own time, on both sides of the Atlantic, are unmistakeable.

Italy’s nightmare began in the chaotic aftermath of the first world war. Disorganised insurrections from the left (the “red years” of 1919-20) were swiftly followed by vicious, systematic reaction from a new kind of far right (the “black years” of 1920-22).

Bands of tooled-up, black-shirted “squads” roamed the cities and countryside, terrorising, beating-up and murdering leftists and trade unionists, and burning down their buildings.

Lying and cynicism were central to the process. When squadristi beat a socialist councillor to death in 1921 their leader mocked: “It’s not our fault if his skull was weak.”

When the fascists lost elections, which was almost always, they simply ignored the results, claiming authority from the “higher” power of patriotism and Fatherland.

Democratic institutions, writes Foot, became “helpless in the face of the blackshirts with their clubs, cudgels and guns”.

As was the case with Hitler later, Mussolini and the Italian fascists could have been stopped. But conservatives, fearing the left, declined to act, the police and army largely stood aside, and the king eventually caved.

Foot is a terrific writer and brings to life some of the key characters and events of the period.

He details the failures and mistakes of the left such as the disastrous bombing of the Diana Theatre by Milanese anarchists. He explains fascist crimes such as the massacre of workers in Turin and the genocidal colonial wars in Libya and Ethiopia.

Mussolini eventually doomed himself by allying with Hitler in the “Pact of Steel”, a strategic overreach that led to Italy’s defeat and his death at the hands of Italian antifascists in April 1945. (A mesmerising chapter explores the many meanings of the public display of his mutilated corpse in Milan.)

Foot’s discussion of the persecution and murder of Italian Jews is also exemplary. “Italy’s Shoah has often been played down, or excused,” he explains. The myths about Italians behaving better or being less antisemitic than other parts of Europe “have been comprehensively demolished by historical research over the last twenty years or so”.

Equally, Foot has no time for the misguided popular image of fundamentally decent Italian fascists as represented by novels and films such as Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. In reality, Italian soldiers and fascists “massacred Ethiopians,

Greeks and Italian partisans and obediently arrested Jews on behalf of the Nazis”.

The bottom line is that there was nothing good about Italian fascism: “It was not a necessary evil. It did not treat its opponents lightly. It failed to bring order and stability. It was directly responsible for the premature deaths of at least a million people, in Italy and across the world. In short, it was a catastrophe.”

And it could hardly be more relevant: “Italian fascism matters. It is still with us, as a warning, a prototype and a possible future.”

• Blood and Power: The Rise and Fall of Italian Fascism. By John Foot, Bloomsbury, £25