Face time

In an age of smartphone cameras the portrait has had its day, right? Not so, artist Patrick Palmer tells Dan Carrier

Thursday, 10th October 2024 — By Dan Carrier

Patrick Palmer in his studio

AS unique as the face staring back at you, portrait painting was once the preserve of the super-wealthy and was seen as an ultimate status symbol.

As mobile phone cameras improve and offer a mind-melting array of options to tart up your photographs, many art experts have wondered if the age of the portrait is dead.

Not so, says Patrick Palmer. He is an award-winning portrait artist – and has seen how special a hand-made piece of art can be. It’s a calling he took up in earnest aged 40, and is now recognised as one of the UK’s premier figurative painters.

“As a child, I was always good at art,” he recalls. “I drew all the time and I wanted to pursue art as a living.”

His talent was recognised by his art teachers.

“After I had finished my A-levels, out of the blue I got contacted by my former teacher, who told me I’d won a prize,” he remembers.

“I hadn’t entered a competition so I was confused – but the teacher had done it without telling me.”

But instead of art, he took a business degree and worked in publishing.

“It wasn’t a passion,” he admits. “I did well but my heart wasn’t in it.”

As he reached 40, he was about to embark on a new magazine venture when his business partner pulled out.

A head-hunting firm offered a good job, but Patrick recalls his reaction to the new opportunity was the opposite of how he would have felt if he was keen.

“I just couldn’t do it,” he said. “I’d reached an age where I wanted to evaluate what I was doing.”

He decided to take life classes and rediscovered his love. A year-long course at an art school in Chelsea further encouraged him – and he decided he could make something of a living from his work.

“At a life-drawing class in Notting Hill I got better at tonal drawings,” he adds. “I was not overly confident but the art took over.”

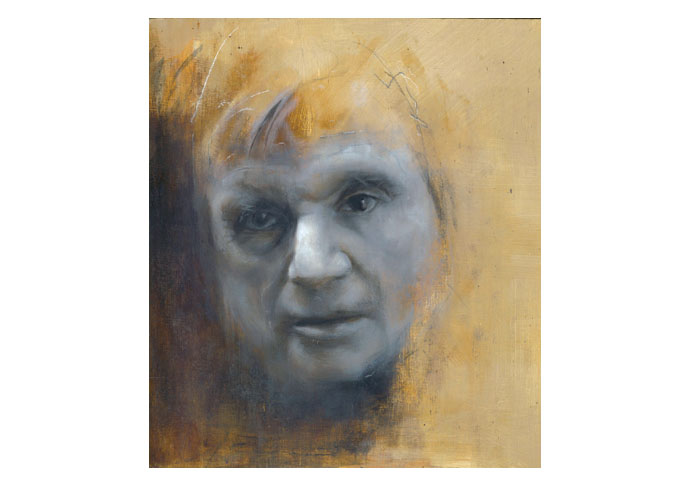

Patrick’s portrait of Francis Bacon

Years of study is required to unlock talent, and Patrick says success is about the hard graft to develop your technique. It’s an element of the trends in art schools in the past 30 years that put abstract concepts ahead of the difficult process of creating figurative work that has seen a falling off of portraiture.

“I have thought about the technical training needed and how art is created for years,” he adds. “If you want to write a really good book, it isn’t about getting lucky. You need a wide vocabulary, and know how to write. You need the tools and that puts you in a better place to create. Art is no different.”

As well as the technical ability to clutch a pencil or brandish a brush, it’s all about the eye, he adds.

“You start by copying carefully,” he explains. “If you are basing the work on a face or a body, then you have to work out what it is about the person that differentiates them and what it is you want to focus on.

“It is about the choices you make as an artist.”

He begins by working out a design as background.

“I work out what looks good and I include what I like – that is my main guide,” he says.

He works on oversized paper or canvas.

“It means I am not restricted and I can cut to size at the end,” he says.

“As you go along, you keep looking, keep looking. You want to find the focal point to draw people in.

“Your eyes are always looking for information so the artist seeks to exaggerate what they feel are the important elements. Think about spotting someone you know 100 yards away. You recognise them by identifying important features. That is what portraiture does.”

Degas is a major inspiration, and Patrick admits that in his younger years he thought Picasso’s work “ugly” but now loves him.

“I look at how artists build up a work, the colours they choose, the interpretive element,” he says.

He has studied the Old Masters in detail but sometimes questions the process.

“With Da Vinci, for example, I do not agree with his idea of cutting bodies open to find out how to be anatomically accurate,” he says.

His work, I Am The Storm

“What you should do is paint what you see. I am not convinced you need to know everything. You are drawing things you cannot really see.”

And then there was the teacher – Patrick says he was fortunate to have been inspired by a brilliant artist whose classes he attended.

Painter Michael Clark was a friend of Francis Bacon and part of the famous Colony Rooms set, which brought artists together in an alcoholic mist at the Soho club.

Michael is the only artist who painted Bacon from real life and has work in the National Portrait Gallery.

“He is very charismatic,” says Patrick. “I saw a portrait he had done in pencil and it was simply one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen

“He is technically brilliant, but he goes beyond that. He has so much to say through his work and would say the most profound things that have stayed with his students.”

Clark guided Patrick over colour – he once told Patrick to put away the tubes of oil as he didn’t understand them yet – and choosing brush sizes. These details add up, says Patrick.

He likens the process to playing with Lego.

“You block out the big parts and then add smaller parts.

“When you build a house from Lego, you use the bigger blocks at the beginning. Portraiture is the same.”

With everyone a photographer with an image-maker in their pocket, commissioning a portrait may sound like an eccentric quirk. Not so, he adds, stating portraiture will never go out of fashion.

“When radio was invented, they said it would be the end of books and newspapers. When TV came, they said that was it for radio.

“But I feel anything handmade, anything where you know its background and provenance, will never lose its value. And each is unique.

“I have 15 people drawing the same model in my life class,” he says. “Every picture they produce is wildly different.

“There is always a bit of the artist in every picture. Personality comes through, and that makes it really precious.”

• Patrick is available for commissions in the run-up to Christmas. See www.patrickpalmer.co.uk