Empty promise

From hippy dream to a vision of hell, Jeremy Worman has committed his memories of living in a squat in the 70s to print

Friday, 5th May 2023 — By Jeremy Worman

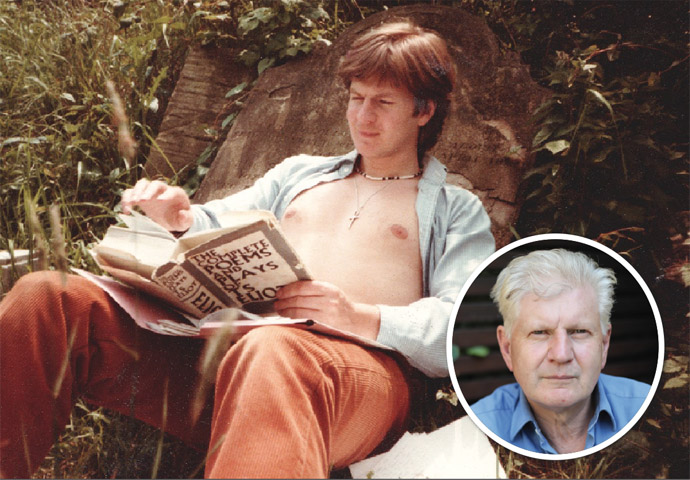

Jeremy Worman – pictured with his younger self, taken in 1977

MY life in the Hornsey Rise squats, between July 1975 until the end of January 1976, was the most intense experience of my life.

There were three GLC blocks – Ritchie House, Goldie House and Welby House – stretching up the steep tree-lined incline of Sunnyside Road, Hornsey. I lived in a top-floor flat of Welby House.

In the three blocks in the borough of Islington there were about 400 people and the squats were reputed to be the largest community of its kind in Europe.

I will never forget my first visit: a barbed-wire perimeter fence erected by the council had been torn down and replaced by psychedelic bunting as if this would transform the negative impact of the council’s actions. As a young man of 21 I entered this world with a desperate sense of hippy hope that my new venture could replace my troubled life so far. I left Welby House with a renewed sense of disillusionment.

Looking back, from the comfort of my Victorian Hackney home now, I knew I had to turn my experiences into an autobiographical novel to come to terms with the psychological and political effects of the Hornsey Rise experience, and of the history of my life that led up to it.

I had wanted to escape my rickety Surrey background of well-to-do alcoholic parents. My aspirations were to live outside the bounds of repressive, “straight” society and to write brilliant poetry. This cheery thought was reinforced when in 1971 I bought a copy of Alternative London by Nicholas Saunders.

This remarkable book explained all aspects of how to squat, survive and prosper in the counterculture. In September 1974 I began a philosophy degree at the Polytechnic of North London and in July 1975 I moved into Welby House.

My visionary hope was to join a collectivist libertarian community (the squats had been going since 1974). For the first week it felt blissful. There was a cosy squatters’ café at the bottom of Hornsey Rise, providing wholesome food, magazines to read, chess and backgammon boards, people to chat to. This place exemplified my hippy dreams where no one was judged by their backgrounds but only by where we were trying to get to – a place beyond the destructive capitalist world.

Initially, Hornsey Rise felt like a refuge for those like me who were trying to mend our broken lives. Instant friendships and romances cut through the stale conventions of the middle-class world.

I met people from every walk of life, class and race. There was a feeling of conviviality and spontaneity I have never experienced since. I joined a small group that was starting an organic vegetable garden.

At its best Hornsey Rise embraced differences without fuss or ideological strictures. That was the upside.

Unfortunately, I was joining this experiment in living towards its end, when drug dealers, thieves and some really heavy characters were moving in. Someone who had been collecting money from us all to buy wholefoods in bulk ran off with the cash. Flats were burgled. Any kind of central organisation had dissipated. Many of the early pioneers who had worked hard to make the place succeed left.

I had an intense love affair that ended tragically. Once, I was in a neighbour’s flat and the door to another room was open: a group of chic young French people were sitting in a circle injecting themselves as if this was a completely normal thing to do. I had lived several years in a few months.

My vision of hope ended in a vision of hell. I moved out, defeated, a few months before the mass eviction in March 1976.

However, the political impact of activist squatters, who front-paged the housing crisis in London, was significant: London councils were forced to develop a new policy of short-term leasing of many empty properties to housing co-ops.

Two years later, with a group of others, we set up Hackney Community Housing [October]. We were given a grant from Hackney Council to renovate a substandard property at 98 Shakespeare Walk, N16, and the services of a hands-on architect to give advice about fitting joists, windows and so on.

We lived there at a minimal rent for two years. The house was returned to Hackney Council in better shape than had it been left empty.

Lives are fractured without decent housing. The criminalisation of squatting in 2012 has taken away even that safety valve for those with nowhere to live. My life slowly found its path: a home, and no exorbitant rent to pay, was the base from which I was able to move on.

The cost of accommodation in London now, especially for young people, has gone through the roof. According to the online newspaper City A.M there are 87,731 empty properties in London. This is a national disgrace. It is time for radical government action.

• The Way To Hornsey Rise. By Jeremy Worman, £12 from www.hollandparkpress.co.uk