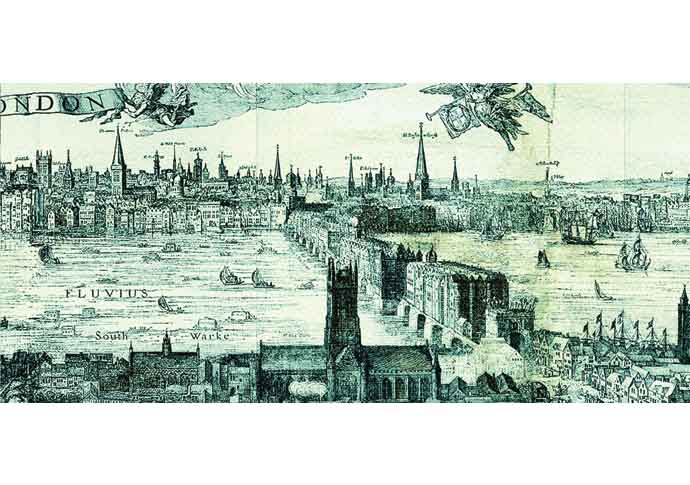

Dirty old town

Historian Kathryn Warner’s new book on 14th-century London proves that grime and crime in the capital is nothing new, says Dan Carrier

Thursday, 18th August 2022 — By Dan Carrier

NARROW filthy streets, a pub on every corner, a city so violent a curfew was permanently in place. Theft punishable by death, starvation a constant threat, and untreatable diseases common.

Welcome to 14th-century London.

In a new book, London: A Fourteenth Century City and Its People, historian Kathryn Warner has delved deep into the archives to bring alive our city of 700 years ago.

Her brilliantly written work reveals the huge differences between Londoners today and of the Medieval period, but also highlights common concerns every urban dweller faces, no matter what age or era.

The Manchester University historian has previously written a biography of Edward II and a study of the houses of York and Lancaster before the War of the Roses. Here, she has created a comprehensive picture of London life between 1300 and 1350 – helped by an array of wills, letters, coroners’ rolls, court reports, pleas, royal writs, chancery documents and more.

Kathryn’s work is split into different topics, covering areas that illustrate the daily to-ing and fro-ing.

The capital was by far the largest city in Britain – and while tiny in comparison to today, it dwarfed other major centres, such as York, Oxford or Bristol. It had a huge population not born in London – up to nine out of 10 had migrated to the capital, and it boasted large numbers from Italy, France, Portugal, Germany, Holland and Belgium.

The European influence was productive and pronounced: Thomas Romeyn – or Thomas the Roman – was elected sheriff and mayor, while there are numerous references to people born in other countries. Fourteenth-century London mimicked today’s multiethnic make-up.

“As well as all the foreign residents, people from other parts of England and also from Wales and Ireland, moved in numbers far beyond counting, to the point where immigrants out numbered those born in the city,” says the author.

Life was unremittingly tough and the streets were scenes of quite shocking casual violence: Londoners were not adverse to harming each other over trifling issues.

Kathryn reveals the murder rate rose through the 14th century and reached numbers seen only in war zones in modern times.

“Londoners stabbed or bludgeoned each other to death, often during a quarrel or while drunk,” adds Kathryn.

“The statistics suggest the murder rate was up to 20 times higher than a comparable sized place today.”

If you were injured – by accident or otherwise – the chances of recovery were based on the severity of the injury and a dollop of luck.

Coroners’ reports show the range of unfortunate ends people met. When someone fell ill, or hurt themselves, it was usual to call for a priest rather than a physician. Hospitals were few and did not rely on learned doctors, rather they were staffed by religious orders who offered the balm of belief as opposed to medical aid.

“Breaking a bone was often fatal,” adds Kathryn.

“Seven-year-old Robert Botulph was playing with three friends on Sunday 16 May 1322 when a large piece of timber fell on his leg and broke it. Robert’s mother Johane found him, rolled away the timber and carried him home.”

He died two months later.

We learn of quite how many pubs and taverns Londoners could enjoy.

With 354 taverns and 1,334 brewers, there was roughly one pub for every 225 people.

“There was a city regulation, repeatedly proclaimed, that tavern customers had the right to see their ale or wine properly drawn in the rightful measure from a cask,” says Kathryn.

“It was also outlawed to have a curtain in front of the entrance to the cellar – and customers could request they see the cellar itself and where the drink they would consume was stored. King Edward II was determined to ensure quality and ordered his sheriffs to go to every tavern in London and make sure they were not mixing good wine with bad, or watering anything down. He brought in a rule that each barrel of wine had its price clearly marked on it, so drinkers knew what they were getting.”

Managing food supplies was critical and reflected in the laws and punishments. “In an age where few people enjoyed an abundance of food and deaths from starvation were not uncommon, people who sold food and broke rules were punished harshly and subjected to public ridicule,” she writes.

Bakers who sold underweight or poorly made loaves were punished, while butchers who sold rancid or off meat were locked in the pillory – and the meat set alight beneath them.

Fields of crops were grown outside city walls, while London imported goods from across the country and overseas. And on its doorstep, the Thames provided an abundance of sustenance. “Edward II, while staying at the Tower of London, is recorded as buying a batch of oysters, 60 unsmoked herrings, three large eels and 73 lampreys, four large stockfish, 20 roach and 100 ‘smelt’ from fishermen,” adds Kathryn.

The homes are described – and reveal the same issues we face today – a lack of space, high rents, and lots of neighbourly arguments over development.

This city had narrow streets, houses pushed against each other and a lack of basic sanitation.

“There is the idea that if modern people could travel back in time to the 14th century, we would need our noses cauterised as otherwise we would be unable to cope with the stench,” writes Kathryn. “This may not be far from the truth.”

She details how muck and rubbish was tipped into the streets, and the Thames was used to dump all manner of refuse, human and otherwise.

“The Thames was not the only smelly, filthy river and the ditches around the city were equally unpleasant,” she writes.

“Edward II paid three men to survey the River Flete, its course being so obstructed by filth…”

Toilets were the source of many legal disputes. Court reports from the London Assize of Nuisance survive in a complete form and reveal much.

“Residents could go to a session to complain about their neighbours, and grumbles about privies or latrines were common, particularly because they were often shared,” she adds.

“One issue was privies which stood too close to a common wall, annoying neighbours with the smell or sewage.”

Topics covered include a chapter titled “Fun” – Kathryn describes how football was banned for a time due to Edward II writing to complain with Mayor Nichol Farndone over “the great noise… caused by rumpuses over large footballs”.

Others chapters include privacy, mansions, roads and weather.

Kathryn has created a comprehensive look at a world that existed where we stand today, offering a chance to time travel back to a London that is both alien but recognisable.

• London: A Fourteenth Century City and Its People. By Kathryn Warner, Pen and Sword Books, £20