Cutting comment

Exhibiting at Swiss Cottage Library, Norman Kaplan’s ‘dangerous’ anti-apartheid linocuts are a reminder of past horrors, says Dan Carrier

Thursday, 21st November 2024 — By Dan Carrier

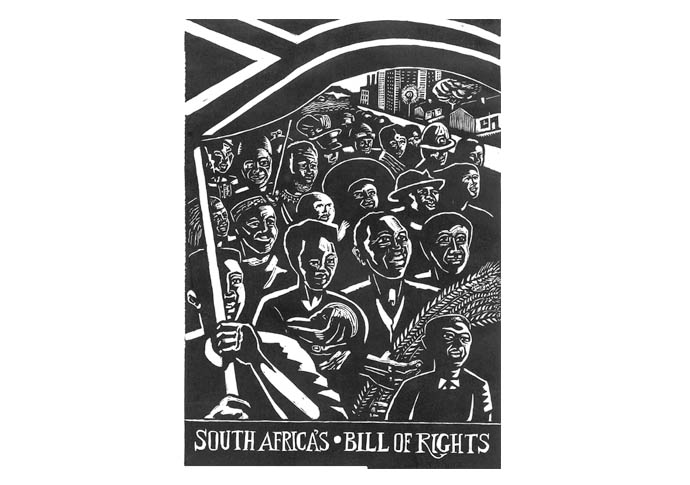

An example of Norman Kaplan’s lino cut artwork

WATCH OUR ONLINE POLITICS CHANNEL, PEEPS, ON YOUTUBE

IT was from a north London squat that Norman Kaplan sent images so powerful that a South African judge called his art “dangerous and subversive”.

Now, 30 years after the liberation struggle, Kaplan’s stunning apartheid-era political work is on display at the Swiss Cottage library.

Norman, who is now back in South Africa, was a key player in the fight against the racist South African government – his years spent in exile in Camden were dedicated to overthrowing the regime.

Working for the anti-apartheid movement in London, he visualised the struggle of his countrymen. His art work was smuggled into the country, helping to finally break the racist regime.

“My formative years were 50s South Africa,” he recalls. “I was a schoolboy soon after the 1948 election. The Nationalists introduced apartheid, it had a fresh and aggressive feel.

“They were bringing in laws and regulations, the Group Areas Acts. As a child, you don’t really understand, you just go with things. You don’t see the conditions others are living in. You only saw black people when they interacted with you as labourers or servants.

“There was a curfew every day at 6pm when black people had to be off the streets and back in townships. This was seen as usual and was accepted.”

Norman – whose family were originally Russian Jews – learned about the Holocaust as a child.

“People had begun to return for the war – uncles, cousins, friends,” he remembers. “We felt it. The Afrikaners were pro-Nazi, and many had been interned. Now, they were being elected as MPs. There was a great fear among Jewish people and many tried to assimilate as best they could, while others became communists, socialists or democrats. They fought for the rights of African people based on their own experiences.”

He was subjected to anti-semitism.

“I was abused by Afrikaner teachers. Sometimes it was subtle, sometimes it was open, and they would call me a dirty little Jew boy.

“We’d get caned if we did not sing the Afrikaners’ anthem correctly.”

There was a febrile atmosphere.

“They wanted to militarise youth,” he says. “It was awful. I ended up walking out.”

After leaving high school, Norman joined an art college and then worked as designer. He had already explored the medium of lino cuts and enjoyed working with the materials.

“I had always been drawing and thought I might like to be an artist, but what type was never clear. The school had progressive lecturers and one became a mentor. He worked in lino cuts and photography.

“My father had died when I was 16, and he [my mentor] became a surrogate. His wife was from Belgium and they had a European aesthetic. He introduced me to artists I had never heard of before.

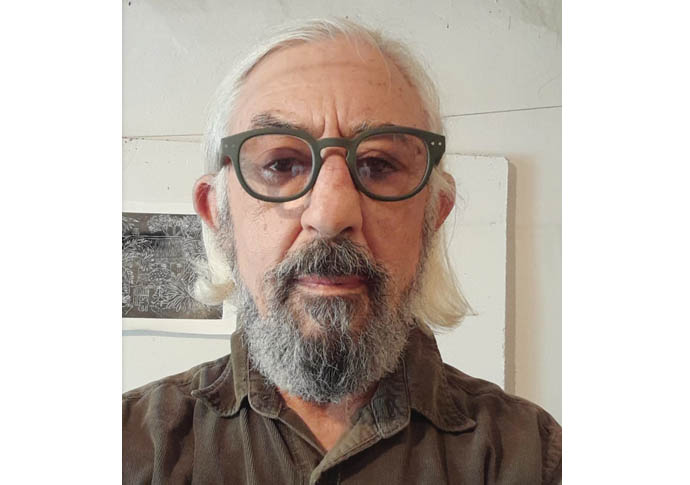

Norman Kaplan

“He was politically conscious and wanted his work to focus on the oppressed and on working class people.”

Living in Port Elizabeth, Norman recalled: “It was small and so you stood out easily.

“I had a black friend who visited me. One day, I got raided. Officers came in claiming they were searching for drugs.

“The plain-clothes police started looking through my books, searching for banned literature, and then they detained me

“I had met a European journalist who had stayed with me briefly, and I had driven them around to take photographs of the townships. The journalist had got hold of some documents that showed links between the Anglo-American mining company and the government, and they were very damaging because it showed labour practices.

“I was quizzed. They eventually let me go and told me they were watching me

“At that point, I knew – I can’t stay here. I am on their radar.”

He had already used his art to make political points, creating an image of the prime minister dressed as a blood-stained butcher.

Then came the Soweto uprising in 1976. Norman had left Port Elizabeth and was working in Johannesburg.

“I was a designer for a liberal newspaper and the violence in Soweto was a turning point. They were shooting children in the streets, and the reaction of people – including journalists – was to support the government.

“I could not stay.”

His partner Bronwyn’s family were from Wales, so they headed to the UK. The pair found a bedsit in Muswell Hill, and would move around 15 times from flat to squat as they found a new life.

“We survived,” he recalls. “I found a job working in animation for a medical company, drawing thousands of illustrations of heart operations.”

Bronwyn’s sister was active in the AAM and Swapo, the Namibian freedom movement.

Norman set to work and his lino cuts made their way to banned publications including the ANC’s Sechaba, The African Communist and the Communist Party’s newspaper Umsebenzi.

“I created lino cuts from photographs,” he says. “I wanted real people, in recognisable places. I wanted people to see themselves.”

Norman had the job of designing a magazine that would not draw the attention of the security services. ANC magazines would appear with a front cover purporting to be a travel publication, with images of wildlife.

As well as illustrations, they would collate lists of people arrested, held without charge, or murdered.

“We were desperate to keep South Africa in the public eye, to get the facts out,” he says.

“Everything was factual – we did not want to do emotive stuff.”

The publications included practical advice for freedom fighters, from guerilla tactics to how to string a piece of wire to stop armoured cars taking deadly shots at civilians.

“We wanted to help the fighters who were risking their lives for liberation,” he recalls.

And with history on their side, Norman and Bronwyn always aimed to return to a free South Africa.

In 1991, when Nelson Mandela was finally released, they could return. And it wasn’t only about putting two feet back on South African soil – it was making sure the legacy of the struggle was secure.

“We came back with thousands of documents, photographs and film,” he says. “We gave it to a University of Western Cape as a historic resource.

“It was gratifying and emotive. Coming home – the heat, the smell – you carry that within you. It was tough – the govern-ment were not going quietly and were fermenting disorder, killing people in town-ships. But we knew we were in the ascendancy.”

• All Shall be Afforded Dignity is at Swiss Cottage Library Gallery, 88 Avenue Road, NW3 3HA until November 28.