Cut price

Salman Rushdie’s account of the near-fatal attack on him is a moving read, says Lucy Popescu

Thursday, 30th May 2024 — By Lucy Popescu

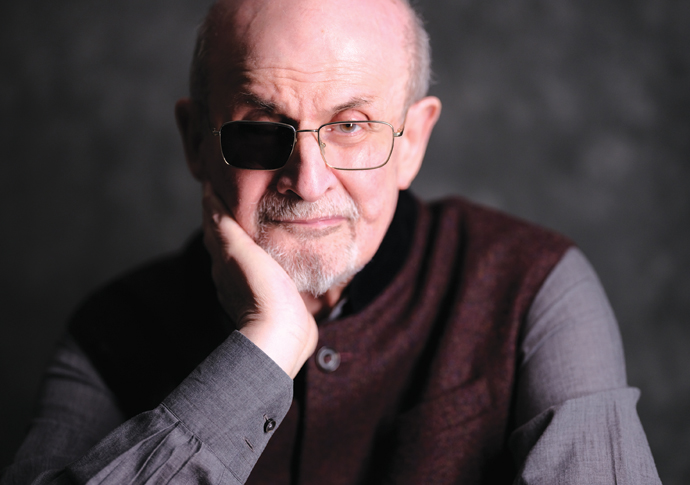

Salman Rushdie, author of Knife [Rachel Eliza Griffiths]

“LIVING was my victory,” Salman Rushdie declares in his extraordinary account of the attack that almost killed him, its aftermath and his miraculous recovery.

On August 12, 2022 a 24-year-old man attempted to assassinate the author onstage at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York. It occurred 33-odd years after the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued his fatwa against Rushdie and all those involved in the publication of The Satanic Verses.

The would-be murderer stabbed Rushdie repeatedly and although unsuccessful in his mission, left him with life-changing injuries to his eye and hand. Knife is Rushdie’s powerful and moving response.

The bitter irony is that Rushdie was at Chautauqua to talk about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm. He has been a supporter of PEN International’s work for persecuted writers for decades.

When I worked at English PEN in the 1990s, and Rushdie visited for events, demonstrations and so forth, I often had to deal with Special Branch, the plainclothes division of the Metropolitan Police, who were tasked with his safety. That all changed just before he moved to the United States in 2000, where he is now a citizen. By 2023 Rushdie clearly thought the years of being accompanied everywhere were behind him.

The book is split into two parts entitled: “The Angel of Death” and “The Angel of Life”. Of his assailant Rushdie writes: “I do not want to use his name in this account… my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation … for the purposes of this text, I will refer to him more decorously as ‘the A.’ What I call him in the privacy of my home is my business.”

While on stage at Chautauqua, Rushdie recalls seeing a man in black running towards him. “Black clothes, black face mask. He was coming in hard and low: a squat missile. I got to my feet and watched him come. I didn’t try to run. I was transfixed,” he writes.

His first thought was: “So it is you. Here you are.” His second: “Why now? Really? It’s been so long. Why now, after all these years?”

Rushdie gives a graphic account of the near-fatal assault that left him blinded in one eye. He ponders the “intimacy” of the attack; the 27 seconds (he learns later from news reports) that they spent together, and recalls afterwards lying in a pool of blood. When his clothes are cut away to locate the wounds, he mourns “my nice Ralph Lauren suit” while another part of him whispers: “Live. Live.”

He remembers the “heroism” of several elderly people who rushed to subdue the assailant and tend to him, and observes: “I experienced both the worst and best of human nature, almost simultaneously”.

In a lighter moment, he recalls the embarrassment of being asked for his weight on arrival at the helicopter ambulance.

Knife is a profound meditation on Rushdie’s life, on art, and second chances, as well as a tender tribute to his wife, poet and photographer Rachel Eliza Griffiths, who goes by her second name. (Salman is also Rushdie’s second name.) Rushdie devotes a chapter to their first meeting, romance, and her response to the attack, but we feel Eliza’s loving presence throughout the memoir. He repeatedly credits her for aiding his mental and physical recovery, how in hospital she wisely refused to let him look in the mirror.

Another chapter is dedicated to Rushdie’s imaginary conversation with “the A”. He decides that “getting myself inside his head and describing what I found there, would be more interesting to me than confronting him… listening to his ideologue’s black-and-white ends-and-means garbage”.

Knife is, in part, about the power of art and literature to confront violence. The book is “my way of owning what had happened, taking charge of it, making it mine, refusing to be a mere victim,” Rushdie writes.

He knows that “art challenges orthodoxy… without art, our ability to think, to see freshly, and to renew our world would wither and die”. Despite the subject matter, it’s an easy read because Rushdie writes with such precision, wisdom and surprising, often self-deprecating, humour. He swiftly recognises that language is his “knife”, offering him the possibility to “cut open the world and reveal its meaning, its inner workings, its secrets, its truths… cut through from one reality to another… open people’s eyes, create beauty…fight back”.

Knife also celebrates “the survival of love”, public and private, and how it conquers hatred. With startling clarity Rushdie observes: “When Death comes very close to you, the rest of the world goes far away and you can feel a great loneliness. At such a time kind words are comforting and strengthening. They make you feel that you are not alone, that maybe you haven’t lived and worked in vain.” Poignantly, he dedicates the book to “the men and women who saved my life”.

• Knife. By Salman Rushdie. Jonathan Cape, £20