Condition: critical

In the Critics’ Circle centenary year, a debate on the changing role of criticism is timely, writes Heather Neill

Thursday, 12th September 2013 — By Heather Neill

Producer Nica Burns: ‘It is important that our culture is given the exposure it deserves’

WHO needs theatre critics? There are, undoubtedly, some actors and artistic directors who would be happy never to encounter them or their works again. It is, after all, possible to get the word out about your show without reviews. Look at the success of We Will Rock You, still running after being universally slated over a decade ago. Look at The Book of Mormon, which, despite some luke-warm reviews, is a hot ticket thanks to an enormous marketing budget and posters featuring theatregoers’ recommendations.

But not every show with a daft storyline celebrates a legendary band – We Will Rock You showcases the music of Queen – or has sufficient money to fund a big noise. And, in any case, surely helping theatres sell tickets isn’t the critic’s main function, is it? What about the importance of informed cultural debate? Don’t critics contribute to an archive of the arts? And isn’t there some value in being able to put in context new work or new versions of the classics? Isn’t there something to be said, in an age of instant democratic comment, for expertise gained from spending three, four or five nights a week in the stalls?

On the other hand, some might argue that an immediate response, from any quarter, is equally valid. Perhaps an exchange of views online could even be said to make for a better, wider forum for discussion.

Shakespeare’s plays, when new, were not appraised by experts, after all, but talked about by audiences, actors and other playwrights.

These are some of the topics likely to be discussed in 100 Years of Criticism: Key Changes, a free conference celebrating the centenary of the Critics’ Circle hosted by the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in Swiss Cottage.

While it is impossible to predict in detail what participants will say – and there will be ample time for contributions from members of the public in open discussion – this is undoubtedly a time of change for the traditional critic. Comment on websites and via Twitter proliferates, readers can take instant issue with the professional and, in any case, how does one define “professional”?

Some respected, non-print, outlets don’t pay their regular reviewers anything at all for their work. So how different are they from a well-informed amateur?

In July the editor of the Independent on Sunday announced that the paper would continue to cover the arts without critics and, as the circulation of newspapers continues to decline, reviewers elsewhere feel less secure.

There may have been a golden era when “the posh papers” (as Jimmy Porter called them in Look Back in Anger) vied for attention on a Sunday and Ken Tynan (in The Observer) and Harold Hobson (in The Sunday Times) each had his followers, but the arts pages have long been referred to sniffily by news journalists as “the shallow end” of their publication.

I can’t remember a time when the arts section (and I’ve edited one and contributed to many others) was not under pressure. How about this to help put things in perspective: “Criticism is passing, as many of us know, through a difficult phase. Its field is becoming more and more restricted. There are fewer papers than there were… and less space even in these.” That was written in 1923, in the first issue of The Critics’ Circular, the journal of the Critics’ Circle. Nevertheless, the role of the critic has survived – so far.

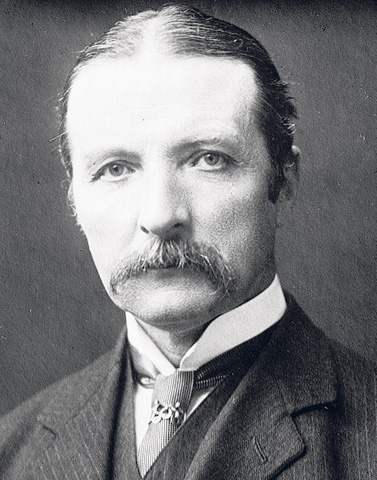

William Archer, first chairman of the Critics’ Circle

The Critics’ Circle was founded in 1913 and its first chairman was William Archer, journalist, critic and translator of Ibsen. Setting up the circle had been a challenge because some critics held themselves aloof, not wanting to rub shoulders with journalists, despite making regular contributions to newspapers. It seems there was a different view then of what constituted the serious part of a paper.

Traditionally, theatre practitioners have been wary of critics. In 1990, the National Theatre Studio held a seminar attended by leading actors, directors, playwrights and journalists. The discussion was animated, but there was a sense that this was a meeting of opposing tribes. While there remains a necessary distance between the “industry” and the critics, there is now often a sense that we must also stick together.

Kate Bassett, until recently theatre critic of the Independent on Sunday, says: “Many of those in the arts industry itself, in fact, keenly appreciate the continuing importance of high-standard newspaper reviews and, far from whooping at the IoS’s decision, are appalled and incredulous.”

While Nica Burns, leading producer and co-owner of Nimax Theatres – and, like Bassett, one of the speakers at the conference – said recently: “It seems to me an irony that in this centenary year of the Critics’ Circle, critics are an endangered species… It is important that our culture is given the exposure it deserves, and it is important that it is written about and commentated on by people who really know what they are doing.”

Whether you agree or disagree, take part in the debate.

• 100 Years of Criticism: Key Changes, the Critics’ Circle centenary conference, is on September 27 at Embassy Theatre, Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, Eton Avenue, Swiss Cottage, NW3 6HY.

• Speakers include Hampstead-based author and actor Michael Simkins, playwright David Eldridge, artistic directors Jonathan Church and Kerry Michael and well-known critics including Libby Purves, Nicholas de Jongh, Michael Coveney and Mark Shenton, chair of the Drama Section.

• The event is free but booking is required. Email criticsday@gmail.com

• Heather Neill, Hon Secretary of the Critics’ Circle Drama Section, is a freelance journalist and critic, and a former arts and literary editor of The Times Educational Supplement, https://heatherneill.co.uk/