Compleat makeover: hooked by seminal book full of ‘strangeness’, folklore… and fish

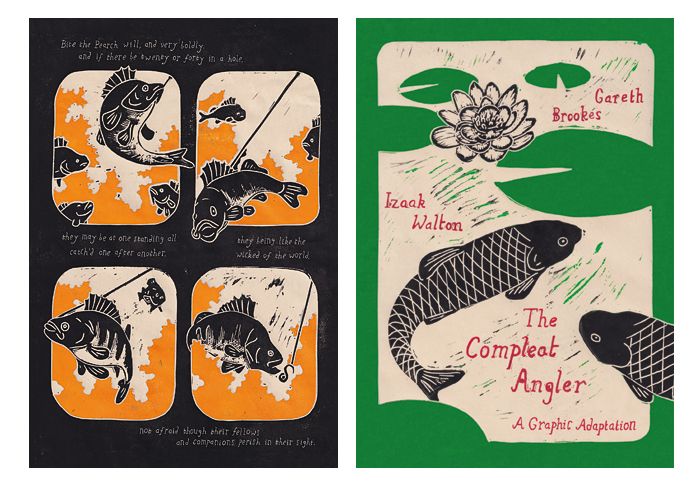

Graphic artist Gareth Brookes talks to Dan Carrier about his adaptation of Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler which was written in the aftermath of the turmoil of the English Civil War

Friday, 13th June 2025 — By Dan Carrier

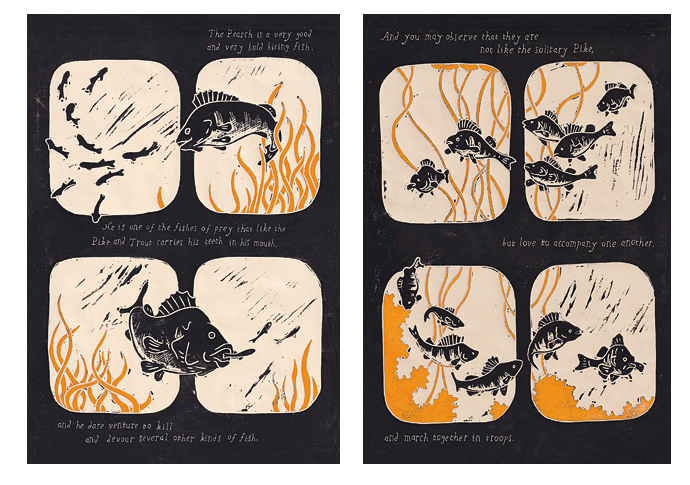

The Perch is a very good and very bold biting fish. He is one of the fishes of prey that like the Pike and Trout carries his teeth in his mouth, and he dare venture to kill and devour several kinds of fish; And you may observe that they are not like the solitary Pike, but love to accompany one another and march together in troops

IT had been a hard few years for Izaak Walton.The draper had watched the conflict between King and Parliament grow more pronounced from his shop in Fleet Street. Peering out of his shop window in the early 1640s, he saw violence in the air. As the resulting strife grew into a full bloodied civil war, Walton, who had Royalist sympathies, must have felt his world was turned upside down.

He had moved from Staffordshire to the capital as a teenager, working in the linen trade. But war saw him leave Holborn for his native Stafford – and it was while stepping away from city life that he penned the first edition of The Compleat Angler, that now, more than 300 years later, is the subject of a new appreciation by artist Gareth Brookes.

Gareth has taken this seminal work in the English language and created a fully illustrated version, published by SelfMadeHero, the King’s Cross-based publishers who specialise in high-end graphic works.

It captures Walton’s warm and holistic approach to angling, rivers and waterlife. Walton opens a window on a long-lost England, a world yet to be blighted by industrial capitalism, a natural environment whose beneficence is exploited by those who live off the land to fill supper plates.

The exploitation of natural resources is not draining but manageable: and Walton’s depictions are of clear flowing rivers full of life.

The author of graphic novels, Gareth studied printmaking at the Royal College of Art and has a PhD from Central St Martin’s in comic studies. Walton’s book is a tome he had dipped in and out of for many years.

He said: “I don’t recall where I got it from, a secondhand bookshop most probably, but ever since I bought it, it’s never left my reading pile. A book to be enjoyed in modest draughts, or luxuriated in during an extra five minutes in bed on an inhospitable winter morning.”

Bite the Perch will, and very boldly, and if there’s twenty or thirty in a hole they may be at one standing all catch’d one after another, they being like the wicked of the world. Not afraid though their fellows and companions perish in their sight

Born in 1593, Izaak Walton headed to London as a teenager. He had a shop in the City and another in Fleet Street and Chancery Lane. He became verger at St Dunstan’s Church and it was there he met the esteemed churchman and poet John Donne, about whom he would later write a biography.

As Charles I began to stir the schism with his MPs that would end with his death on a Whitehall scaffold, London was firmly in the Parliamentarian camp. The crisis Royalists faced when the king was beheaded and the Roundheads won the Civil War had a profound effect on Walton: those on the Royalists side believed the king was God’s representative on Earth, and the idea that Charles could be removed prompted a crisis of faith.

Following Oliver Cromwell’s victory at Marston Moor in 1644, Walton settled on a small farm in the village of Shallowford, which had a river meandering through a field. It gave him the perfect topic to turn his pen to and he began making notes that would become The Compleat Angler.

Between the covers are his thoughts on perch and carp, tench and gudgeon, eels, salmon and pike; as well as frogs, otters, water voles and other riverbank creatures. He returned to London in 1650 and the book was published in 1653. For the next 20 years Walton continued to edit the volume which ran to five new editions.

It is more than a practical guide to catching and cooking fish. Walton poured his lyricism into the lines.

“The book’s imagery really appealed to me,” says Gareth. “When I was a child I loved animals, and I loved fishing. I had a 1950s book called Mr Crabtree Goes Fishing – I read it over and over.

“My previous works have been based on darker subject matter. I wanted to take something positive and joyful.

“As I read his book, the imagery really jumped out. Izaak Walton’s book is full of strangeness, it is esoteric and eccentric, it is full of folklore.”

And Gareth says while Walton was a Christian, he had a different approach from others of the period.

“He had quite an advanced notion of humans living with nature – not above it, not controlling it, as many believed. It was not the usual ecclesiastical approach,” he says. “Today, we still have this idea that nature is somehow for us, not part of us.

Graphic artist Gareth Brookes

“For Walton, it was about a balance and anglers often understand that. It isn’t easy to catch a fish. But you do this in a beautiful environment and you learn to respect nature. There is an English pastoral feel that runs through his work.

“In Britain, we do have a gentle environment – there is nothing that is going to eat you, stomp on you or charge you out there. It is a congenial natural environment and Walton recognised and celebrated that.”

Gareth has a lifelong love of being by the water. His grandfather had a boat and his father took him angling.

“At the time of Walton writing, his world had been turned upside down,” Gareth adds. “All of the certainties people felt had been disrupted and disturbed.”

This was an England that had seen a rise in Armageddon sects who thought the Civil War was the beginning of the end of the world, and there was also a rise in non-Conformism. The war also radicalised workers. It prompted the rise of the Levellers and Diggers and other proto-socialist groups.

“Walton found comfort in nature, doing something that was gentle, unchanging. Time spent by the riverside afforded a sense of calm and permanence. “And he comes over as a really nice bloke. He was always writing about his friends. He connected with people over being in nature.”

It wasn’t just dry instruction, but verse, poetry, anecdotes, and contributions from experts in various fields.

His lyricism remains glorious:

The Mighty Luce or Pike is taken to be…

The tyrant of the fresh water…All pikes that live long…Prove chargeable to their keepers because their life is maintained

By the death of so many other fish.

And translating some of Walton’s quirkier passages was a joy, he adds: “I am not sure how much it stands up. Some of it is really quite weird, and some of the recipes he suggested sound quite disgusting.

“He writes some strange things, like telling a story of the frog that grabs onto a pike with teeth and eats its eyes.”

• The Compleat Angler: A Graphic Adaptation. Words by Izaak Walton. Art by Gareth Brookes. SelfMadeHero, £14.99