Class act

Dan Carrier recalls the late James Roose-Evans, the man who gave Hampstead its theatre

Thursday, 10th November 2022 — By Dan Carrier

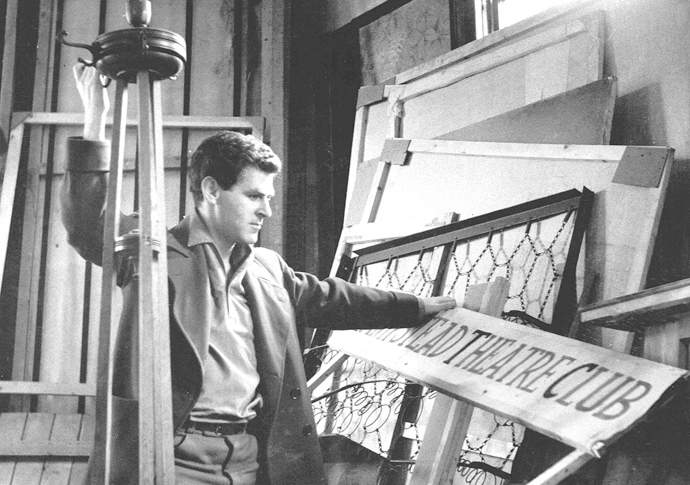

James Roose-Evans, the founder of Hampstead Theatre. PHOTO: HELEN CRAIG

FROM the thousands who have nestled down on a Hampstead Theatre pew and been entertained, enlightened and informed, to the scores of actors, directors and writers who found inspiration, James Roose-Evans was a seminal figure.

The founder of Hampstead Theatre, who has died aged 94, was a champion of the dramatic arts, an acclaimed director, a distinguished writer, a priest and much, much more besides.

It was 1959 when James – then working as a theatre director – came up with the idea of Hampstead having its own theatre.

He visited the vicar at Hampstead Parish Church and booked its hall, next door to the Everyman cinema, for a series of dates.

When funds were tight, James would revert to a trick he had learned as a teenager busking outside West End theatres.

He’d recite Dylan Thomas to the Everyman queue and earn the cash to pay to cover the printing of that night’s programme. The theatre was limited by the fact it shared the hall with the Cubs and Brownies. Briefly, James considered using the room above the Three Horseshoes pub opposite, where they rehearsed and stored sets. It would later become Pentameters, but a fire escape was needed at great expense, so the theatre was still searching for a venue.

Hampstead Borough Council stepped in: they gave a £7,000 grant to provide the shell of a prefab on land in Swiss Cottage, where Sir Basil Spence was due to build a library and swimming pool.

James raised £10,000 and in 1962, Dame Peggy Ashcroft unveiled a plaque marking the beginning of the theatre in a permanent location.

James managed to balance both the need to constantly be soliciting help and funding to finding ground-breaking work that he wanted to stage and direct. It is a sign of his many talents that he was successful at both.

James ensured the theatre lived “by our wits, talents and a great deal of risk taking”.

It worked: in recent times, the theatre has had a £13m re-build a few yards from the original venue, and is a cornerstone of London’s theatrical landscape.

The Hampstead Theatre Club – at first, there was a membership to get round a licence issue – scored numerous successes.

James could not afford adverts so reviews were vital.

One day, when audiences were scarce, James decided to revive the Noel Coward’s Private Lives. It was at a time when Coward was seen as yesterday’s man, but James called it a “masterpiece of wit and style”.

He persuaded Sunday Times columnist Harold Hobson to review the play and word reached Coward.

A telegram duly arrived, telling James that Coward was in London to see the Queen Mother, and he would like to see the show. He could only make the Tuesday afternoon – but no show was programmed then, so James got the cast in and gave an auditorium’s worth of tickets away.

“A limousine drew to a halt and out stepped the Master,” James recalled. “At the end of the performance there was loud and deeply affectionate applause followed by cries of ‘Author!’ Coward stepped on stage and joined hands with the actors.”

James in 1959 inside the Three Horseshoes pub

Coward, who had previously refused to permit the work to go to the West End, relented after watching James’s production.

It was one of many. The theatre saw world premieres of Tennessee Williams – he and James were in regular contact – and Harold Pinter. Williams had seen his production – twice – of Adventures in the Skin Trade and wrote to James, asking if he would work with him.

James was born in 1927, and his childhood was marked, he said, by his mother’s wanderlust. She would buy a home, do it up, then become bored and move on: he attended 17 different school.

His father had been a “gentleman jockey” and met his mother at the Cheltenham Races. Sadly, James would later write of an abusive relationship he witnessed in his childhood. His brother Monty, went to boarding school, and then joined the Merchant Navy, missing much of the unhappiness.

James did his National Service in 1946, and was posted to the Education Corps, but he faced persecution. In his autobiography, Opening Doors and Windows, he recalled being set upon by six sergeants. The beating he received – which was homophobic – was so bad the following morning he volunteered to be posted to Palestine, then riven with terror attacks.

Instead, he would be stationed in Glasgow and then Italy – an important moment spiritually as he became immersed in Catholic ritual. He would take Communion, and although later in life he reverted back to Anglicanism, he would say the Roman church had an enduring influence on him.

Leaving the Army, he won roles as an actor. His agent, who he described as a “large toad with glittering eyes”, got him roles in comedies in the East End, where audiences sat at rough trestle tables drinking beer from jugs, smoking and talking.

He passed up a place at Oxford to pursue his career – but was turned down twice by Rada. Instead, he gained experience performing across the country. Life as a jobbing actor was tough and James felt it: a trip to Benedictine monks in Yorkshire persuaded him that it may be a way of life for him. He enrolled to study at St Benet’s Hall in Oxford to see if that was the case.

It was here he met David March, and the couple began a relationship, living together for a time.

While theology, philosophy and meditation would play a key role in his life, James decided monastic orders were not for him and he returned to the stage.

After working all over the country and a spell in America, he took up a teaching post at Rada, his students including John Thaw and Mike Leigh.

In 1958, he met Hywel Jones, a farmer’s son from mid-Wales, who worked in a library in Bedford Square. It was the start of a deeply loving relationship that would last over 50 years.

While managing the theatre, directing and writing, James took on another project: he had bought his parents a rectory in the remote Welsh hamlet of Bleddfa in 1970.

At the time James was writing a column on meditation in The Church Times and the rector of the Bleddfa chapel became a friend. In 1973, he told James the chapel was due to be closed.

James saw the chapel could be something more than a place of worship, and in time, with his and other’s dedication, it became owned by the Bleddfa Trust, an arts project that considered the relationship between faith, spirituality and culture.

Aged 90, he published a daily diary. In it he wrote: “I have not wasted my life, but lived it to the full. It is hard not to relish the serenity of someone who has known much happiness and still finds plenty.”