Cimarons stripped

Hugely influential but cruelly forgotten, The Cimarons have reformed and are due to play The Underworld later this month. They’re also the subject of a documentary, as Dan Carrier discovers

Thursday, 3rd October 2024 — By Dan Carrier

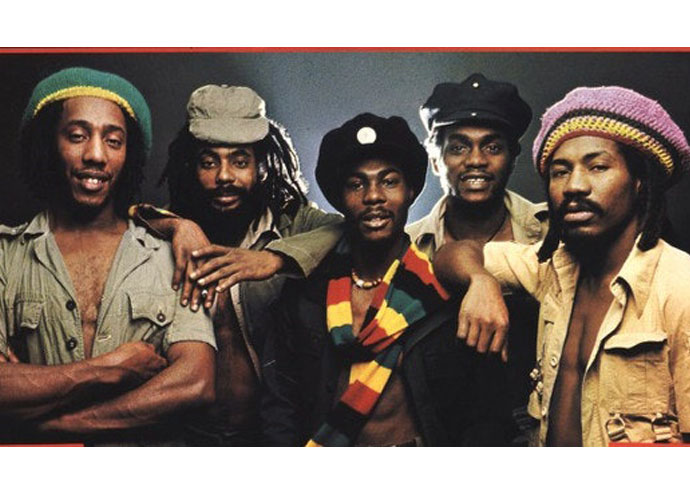

The Cimarons in Harder Than The Rock [Dennis Morris]

AS teenagers they spent their evenings at a Kilburn youth club. Jamaican-born, they experienced the same challenges of settling in a new country – and found a way of expressing it.

The youngsters formed a band: they called themselves The Cimarons, after a popular Western series. And they would become the group that can truly say they were the first-ever European-based reggae band.

Now, 30 years on after slipping from the public eye, they have reformed and are playing a comeback gig in Camden Town at the end of October.

Film-maker Mark Warmington has created a documentary that tells the Cimaron story, follows them as they reform, and casts a light on north west London’s impact on global music.

The Cimarons played with the best – Bob Marley used them on tour, they worked with the likes of Toots and the Maytals and Lee “Scratch” Perry.

Guitarist Locksley Gitchie told Review how revisiting the band’s roots was a reminder of the vibrancy of north London’s music scene.

“It took me back to the 1960s,” he recalls. “It was a great time for music. When we first started playing together, I had come through the ska era and rocksteady was the thing. The basslines were amazing – and even today they are used. They are that timeless.”

Locksley moved to London from Jamaica as a 12-year-old. His mother had landed a job at Kodak in Park Royal, and his sister had a job as a nurse. They had settled in Harlesden.

“The Windrush generation brought London many West Indian families – and the music came with them,” he says.

Soon the home of reggae came calling.

“We were told we played the music too fast,” he says. “We went to Jamaica and Sly and Robbie [the legendary bass and drum duet who played on countless releases] were impressed with us. They were knocked out by our sound – they couldn’t believe what they were hearing.

“Reggae was slower in Jamaica. In London, we played for punks and Two Tone audiences as well as roots reggae fans so we played it faster. It gave it a slightly different feel.

“Sly and Robbie took that on board and with their hit, No No No, they played it at our pace. So we were quite influential without even knowing it.”

And he recalls how growing up in north-west London offered challenges as well as solidarity. “There were English youths who would chase us,” he says.

“But the area was working-class and so there was a sense of solidarity. We never ever had problems with the Irish community, for example.

“There was a lot of racism but our music really broke down the barriers. We took our reggae into clubs where no black people had ever been. We were supported by some really tough guys – The Jam and The Clash and UB40. That opened the doors. The racism is still there, because of a lack of understanding and a lack of knowledge. It was mob ignorance, and music breaks that down.”

As punk took hold, The Cimarons found new audiences: they were supported by The Clash at the Electric Ballroom in 1978, and as members of the Rock Against Racism movement, sold out The Roundhouse.

Mark Warmington said it was “by happy accident” he chronicled their incredible story.

“I wanted to do something music-based,” he said.

“I had played in bands and grown up listening to reggae and dub.”

At the time, Brent Council was running a reggae retrospective called No Bass Like Home – and Mark was fascinated to hear more about clubs in Willesden, Kilburn and Harlesden. Having lived in the area for 20 years, he found a community of musicians and venues he hadn’t known existed – and tracked down Locksley.

“I hadn’t heard of the band,” admits Mark.

“He was unbelievably friendly, open-minded and trusting. He is incredibly modest and was regaling me in a factual way of how the band played with Bob Marley on his first tour.”

Little original footage survived – Mark embarked on a detective hunt to source as much as he could – and the band, now reformed, performed live for the camera crew.

“There is a lot of history to tell but the issue I faced was simply that they are quite an obscure band today,” he says.

“There was not reams of footage. I did a lot of detective work.”

He had some joy in Ireland, where the band had performed in 1978. “I asked people in Cork and they said ‘Yes, we remember them – a load of black fellas with dreads. They played here.’”

The story is not just about rediscovering a seminal moment in London musical culture, it is about recognising wrongs done.

“They were left high and dry by the industry,” adds Mark.

“They were never paid properly. They were given really small amounts for session work for really big artists. But they were pioneers, originators. I asked Aswad if they’d be in the film – they said

‘The Cimarons were our mentors – it would be an honour.’”

Mark believes the band suffered from the fact they were so inventive.

“They were almost too early,” he thinks.

“They were always ahead of the curve, and that affected their long-term success.”

They were playing reggae before it became ubiquitous.

“They’d be the trailblazers, then others would come in and cash in on their work,” says Mark.

“For example, McCartney asked them to do reggae versions of his songs. It prompted Aswad to get into the pop sound. They did it two years later with Don’t Turn Around, which was another game-changer inspired by The Cimarons.”

Current lead singer Michael Arkk is well-versed in reggae – he was born in Jamaica – yet The Cimarons were not on his radar.

“The first time I heard of them was the day I met them,” he reveals.

“A friend had told me The Cimarons were reforming and looking for a singer. We started talking and we have not stopped since.”

He found old footage and realised he had seen them perform before.

“I saw Top of the Pops and thought ‘This is not possible – their names should be everywhere,’” he adds.

Growing up in Jamaica, Michael was aware of the difference between British-produced reggae and the Jamaican genre.

“In Britain, you could not find the rhythm and bass players at first,” he said.

“The music in England sounded light and tinny. But The Cimarons covered a Bob Marley hit and did it very well. It went to number one – and showed there was something very unique about them.”

• For tickets to their gig at The Underworld on October 27 go to www.theunderworldcamden.co.uk/event/cimarons-27th-oct-the-underworld-london-tickets/