Burn baby burn

As Sumer Is Icumen In (at last), now seems like a good time to take a fresh look at the cult movie, The Wicker Man, says Stephen Griffin

Thursday, 9th May 2024 — By Stephen Griffin

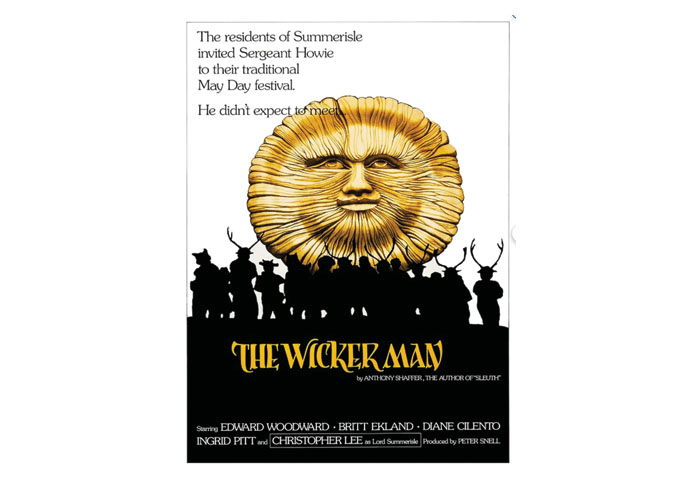

Britt Ekland’s poster for The Wicker Man’s re-release

IT was the gut-wrenching sound that I remember most clearly; the chilling cra-a-a-ack of shattering glass. It was only then that I drank in the full horror.

I’ll explain: a couple of decades ago, the Swedish actress Britt Ekland auctioned off some of her possessions, one of which was a poster for a film she hated as much as I loved – The Wicker Man.

My wife made the successful bid and presented it to me one Christmas. Alas, the frame wasn’t in great nick and my clumsy attempt to repair it resulted in my smashing the Ekland-inscribed glass.

It was time to keep my appointment with the picture framers.

For the uninitiated, The Wicker Man is a – possibly the – prime example of what has become known as “folk–horror”. It’s the tale of a virginal Christian copper who rocks up at the isolated Hebridean island of Summerisle in search of a missing girl. To his horror, he finds the islanders – presided over by the enigmatic and charming Lord Summerisle (a rare smiley role for Christopher Lee) – adhere to the old religion: they’re pagans. As the plot unravels it’s clear he’s been… well, let’s just say it doesn’t end well.

The film is an almost textbook example of a cult movie; a picture that according to Collins dictionary “a certain group of people admire very much”. Sadly fan boy Nicolas Cage admired it so much he starred in a misguided remake… but the less said about that the kinder.

The original The Wicker Man, however, has become the stuff of legend, its rescuing from obscurity being a huge part of its mythology.

You see, it was said its production company, a newly sold-on British Lion, loathed it. Unsure of its market or how to promote it, some say British Lion attempted to bury it – literally, if rumours of its negative being used as hardcore for the M3 are true.

According to many, most vociferously Sir Dracula himself, the film was butchered to make it into a supporting B-feature for its stablemate, Don’t Look Now. Mind you, Lee’s continual moaning may have been coloured by the fact that the slimmed-down version resulted in many of his more verbose scenes hitting the cutting room floor. He didn’t appear to understand why an interminable scene about apple husbandry failed to make the final cut.

Many books have been written about the film but the latest – John Walsh’s handsome The Wicker Man: The Official Story of the Film, published to mark its half century – is one of the best. It’s not that it’s particularly well written – it comes across as a series of features – it’s that the author has unearthed many new (at least to me) facts about the film and talked to a number of hitherto reluctant contributors, including Ms Ekland.

I knew, for example, that Peter Cushing was approached to play the policeman, a part that went to Edward Woodward, but I didn’t know that both David Hemmings and Michael York turned it down. And in a move that would surely redefine the term “horror movie”, I learned Michael Winner had expressed an interest in the project.

London-based author and film-maker Walsh also spoke to the man viewed by many of the faithful as the villain of the piece, one of the British Lion executives who ordered the cuts, Michael Deeley.

But Deeley makes a good case for the defence, pointing out that the somewhat unconventional subject matter made securing a UK distribution nigh-on impossible. He claims that had he not made the second feature-making excisions, the film might never have seen the light of day.

It has to be said the film’s first-time director, the late Robin Hardy, doesn’t come out well.

Filming in Dumfries and Galloway in a freezing October pretending to be May, it wasn’t an easy shoot but according to several crew members Hardy was mercurial and difficult, one day arriving on set and announcing that on hearing the movie’s Cecil Sharp-researched folk songs, he was making a musical!

It’s generally accepted that the film really belongs to its writer, Anthony Shaffer. The twin brother of Peter – the man who gave us Equus and Amadeus – Anthony Shaffer was responsible for the equally playful Sleuth. Both Shaffers were inordinately fond of games… and that, Hardy insisted, is exactly what The Wicker Man is.

Although much altered, the basic premise for the film was inspired by actor-turned-author David Pinner’s novel, Ritual. At the time of writing it, Pinner was appearing in The Mousetrap and one day was so engrossed in his own plot he forgot to go on stage and do away the victim. As he remembers it, the unfortunate actress was therefore forced to strangle herself.

No academic tome, this visually arresting paving slab of a book is more of a coffee-table book. Actually, if you screwed a leg on each corner it’d make a pretty good coffee table.

Well done, Titan. As Lord Summerisle would have it: You did it beautifully.

• The Wicker Man: The Official Story of the Film. By John Walsh, Titan, £39