Borderlands

A poignant show offers a snapshot of Ukraine art, as John Evans reports

Thursday, 11th July 2024 — By John Evans

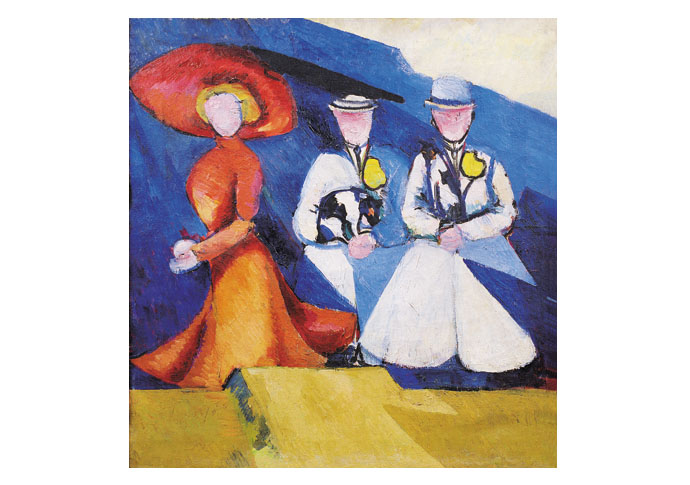

Alexandra Exter, Three Female Figures, 1909-10, oil on canvas, 63 x 60cm National Art Museum of Ukraine

THERE’S regular confusion of terminology when politicians refer to nation, state, nation state, country, province, colony, territory, and so on.

Sometimes it’s genuine, more often it’s opportunistic, aspirational, or simply dishonest.

Take Sir Keir Starmer’s first speech as PM on Friday, referencing first “this great nation” then “country” then “Britain” then “four nations” and not a mention of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland is not a nation and never will be.

And to see the relevance we need only look to the Royal Academy of Arts new Ukraine exhibition.*

A publicity release defines its terms: “Geopolitically, Ukraine had for centuries been a borderland, with its territory divided between various empires and its people not perceived as a single nation until the late 19th century. Yet there were short periods of independence crucial for the formation of a Ukrainian identity. This complex historical background resulted in a vibrant amalgamation of encounters, a fusion of Ukrainian, Polish, Russian and Jewish elements that created a distinctly local cultural profile.”

Note the shift from borderland, territory, nation, and identity, to local!

Volodymyr Burliuk, Ukrainian Peasant Woman, 1910–11, oil on canvas, 132 x 70cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid [© Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid]

In any case an area which has historically seen serious conflict.

What we actually have in this show is a snapshot, some 70 artworks from the early 20th century, defined as an essential “chapter of European Modernism”.

In slightly different formats, the exhibition has been seen in Madrid, Brussels, Vienna, and Cologne, many of the works having been moved out of Kyiv’s art museum and its museum of theatre, music and cinema as the current war with Russia escalated.

Artists featured include Alexander Archipenko (with a single bronze and marble sculpture Flat Torso); Sonia Delaunay, who was born Sara Stern in Odesa in 1885; Alexandra Exter, with her pioneering theatre designs; and avant-garde painter and theorist Kazymyr Malevych, born in Kyiv but so often referred to as “Russian”.

Indeed the development of the “Modernism’ here defies simple labels with its wide range of artworks.

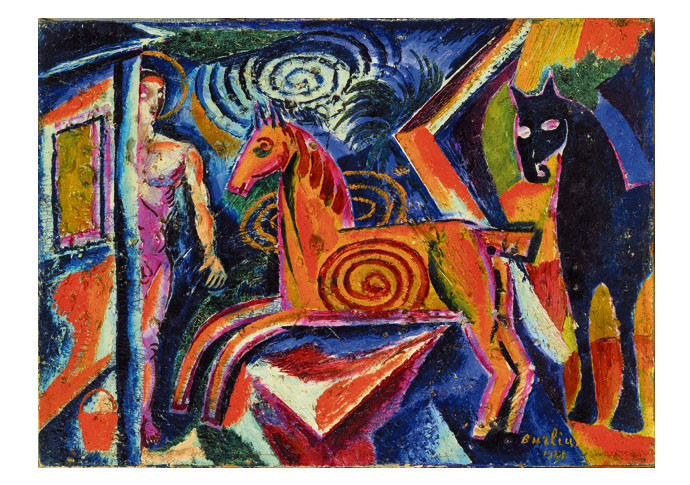

Davyd Burliuk, Carousel, 1921, oil on canvas, 33 x 45.5cm, National Art Museum of Ukraine [© The Burliuk Foundation]

Perhaps the only thing that brings that development together is, as the Madrid experts noted, that it “…took place against a complicated socio-political backdrop of collapsing empires, the First World War, the revolutions of 1917 with the ensuing Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-21), and the eventual creation of Soviet Ukraine”.

Themed sections look at: the Cubo-Futurist movement; the role of theatre design; the Kultur Lige, which brought together young artists “to foster a synthesis of the Jewish artistic tradition and the European avant-garde”; early “Soviet Ukraine” and the artistic hubs of Kharkiv and Kyiv art institute; and the “Last Generation” whose artistic activities were cut short in 1932 with the abolition of all independent art groups and imposition of socialist realism.

And horrendous famine.

Artistic endeavour can be brutally seen off by persecution, suppression, or, as in a number of cases here, executions. For example, after the Soviet authorities “Ukrainisation” from about 1923 Mykhailo Boichuk and his group created artworks for public buildings and spaces. But Boichuk and others group members would perish during the Stalinist purges of the intelligentsia.

* In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s runs in the The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BD until October 13.

Details and booking: 020 7300 8090 or see www.royalacademy.org.uk