We speak to the author of Denmark Street: London's Street Of Sound

Denmark Street – aka Tin Pan Alley – might be synonymous with the music industry but, as a new history explains, it’s so much more. Dan Carrier wanders down memory lane...

Thursday, 19th October 2023 — By Dan Carrier

Tin Pan Alley

IT is a trial of strength to attempt to name drop the people who have visited, worked or played a role in making Denmark Street the place it is. It’s a who’s who of British music over the past 100 years, and would be easier to list those in the music industry who don’t have a link to Tin Pan Alley.

Suffice to say, a new book tracing the history of Tin Pan Alley, Denmark Street: London’s Street of Sound by journalist Peter Watts is full of the stories of the people who have climbed on a stage and entertained us.

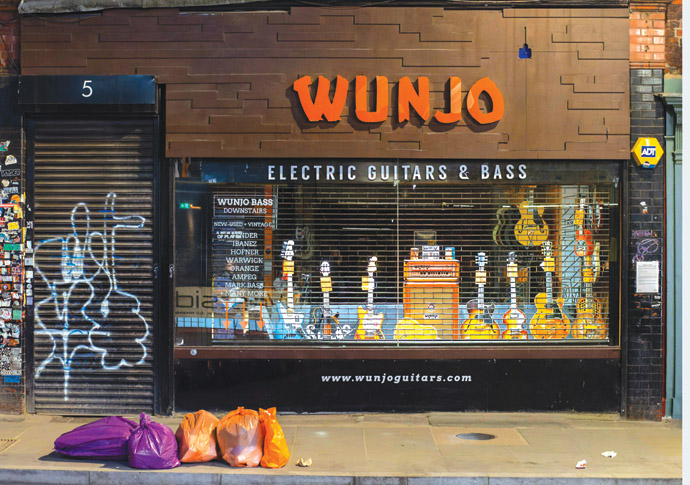

But Peter also delves behind the facades, behind the shiny rows of guitars in windows, to talk about the music industry in a wider way.

He looks at the business practices, evokes names that carved pop culture from behind publishers and record label exec desks. The stories cast light on the ever-changing social milieu of a central London street with a unique place in global entertainment are wonderful and worth preserving.

Peter is a great guide. He has visited TPA for decades. As a teenager, he’d pop down with friends looking for drum sticks or guitar strings, and was charmed by its seductively seedy feel. Later he worked at Time Out, based around the corner in Tottenham Court Road, and then as a freelance music journalist, Denmark Street had rich pickings for stories and features.

Denmark Street and music began a long relationship due to an awful mining disaster in Cumbria in 1910.

An explosion and tunnel collapse led to the death of 136 men and boys. The public grieving saw a song called Don’t Go Down The Mine, Dad catch the public mood. It became a smash hit and the owner of the rights, Lawrence Wright, sold more than a million copies. He donated a halfpenny from each sale to a miners’ fund, and used the rest to leave his home in the Midlands and head to London.

“According to Tin Pan Alley mythology,” says Peter, “on arrival at St Pancras station he hired a wheelbarrow and packed it with sheet music, his violin, a mandolin and pushed it to Denmark Street, where he rented a basement for £1 a week.”

Publishing was a big deal. In the absence of records or radio, a song would be sung at a music hall, and if it was popular, they’d be rushed into print.

“Every pub had a piano around which people would gather. A hit – which usually meant one with a memorable chorus and a melody that was easy to master by an amateur pianist – could shift hundreds of thousands of copies. Sheet music publishing could be an extremely lucrative business.”

With roots in music hall and variety, its warren of poky offices and spaces were used for “publishers, songwriters, pluggers, bookers, agents, rehearsal spaces, record labels and demo studios,” writes Peter.

It was where The Beatles signed their first publishing contract, and where The Rolling Stones recorded their first album.

Peter Watts

From the 1970s onwards it was also home to instrument sellers, drinking dens and a greasy spoon where musicians chewed the fat over a cheap cup of tea (and David Bowie sought a backing band).

Peter makes short work of the pre-music history, describing how the notorious Rookeries in the parish of St Giles was best to avoid, rife with plague and poverty.

It later was the place for a songwriter to earn a few quid. The phrase the Old Grey Whistle Test, which is the title of the BBC music show, comes from such sales. A song writer went into a publishers and would bash out their composition on a piano. On the doors of these offices were former soldiers, wearing their grey suits. If they liked what they had heard, if you had a hit, the chances are you’d hear the old soldier on the door, whistling your melody – hence the Old Grey Whistle Test, whistle rhyming slang for suit, conjuring up a double meaning.

Publishing houses from Lawrence Wright to Noel Gay attracted the likes of Elton John and his song-writing partner Bernie Taupin, saw Oliver! Composer Lionel Bart selling his wares, and Paul Simon famously having Sound of Silence and Homeward Bound turned down. It was home to the NME and Melody Maker, and then from the 1970s onwards came the shops such as Andy Preston’s Andy’s Guitars – he would also establish the renowned 12 Bar Club. Peter tells us of the success of Cliff Cooper of Orange amps, who at one point owned half the street.

It is not all guitars, performers, and quirky characters.

Denmark Street was the scene of one of the biggest mass murders in British history. In 1980, 37 people were killed when a can of petrol was poured through the letter box of El Dandy a private club without a drinks licence and no fire escape. The inferno was so severe that many of those who died could only be identified by their teeth.

It sparked a man hunt, helped by survivors. A student recalled a man left the bar griping about his change, saying “one of these days this place is going to burn”.

Another witness said they had seen the same suspect attempt to start a fire in Denmark Street a fortnight earlier.

The suspect, John Thompson, was caught but did not confess at first.

“We brought him to Tottenham Court Road, marched him into the charge room past 28 dustbins of ash and got from him where he had bought the petrol,” recalls an officer.

“He claimed he’d left it there and someone else started the fire.”

Thompson received a life sentence.

Other clubs were targeted by police. The Back Beat sold cannabis and the response was like something out of an action film – snipers on roofs, abseiling officers crashing through windows. They found cash, cannabis, and machetes.

“The club advertised in student magazines, had a pool table, TV screens and a laminated membership card.

“Punters paid a £2 entry and went upstairs to hand a tenner through a hole in a wall and receive a bag of weed in return. Drugs were smoked and there were warm cans of lager if that was your preference. It was an Amsterdam-style coffee house in the heart of London, operating with brazen indiscretion.”

The police were wise to it. PC Steve Washington, who patrolled Denmark Street, told Peter “if he took one step towards the front door, it would be slammed shut and bolted. It was like a fortress. Doors had steel shutters, there was CCTV on the exterior and lookouts in the surrounding streets. The dealers were believed to be armed with guns, machetes and electric cattle prods.”

In 2016, work to redevelop Denmark Street began. The £1billion redesign by developers Outernet includes two new venues, one replacing the iconic 12 Bar.

“Critics of the new development point to the manufactured and crassly monetised nature of it all, but Denmark Street was always about commerce,” adds Peter.

“It is the dirty secret at the heart of the Tin Pan Alley story: it might trade in music, but it has always been about how to make money from a melody.”

For the history buff and the music lover, Peter has produced a thoroughly researched and great-to-read story about a short West End street with a global impact.

• Denmark Street: London’s Street of Sound. By Peter Watts. Paradise Road Books, £20