‘Ave a banana!’ Why the Strand holds a special place in the minds of Londoners

The Strand’s history is one of commerce, invention and communication, as a new book reveals. Dan Carrier takes a trip down the thoroughfare

Thursday, 27th February 2025 — By Dan Carrier

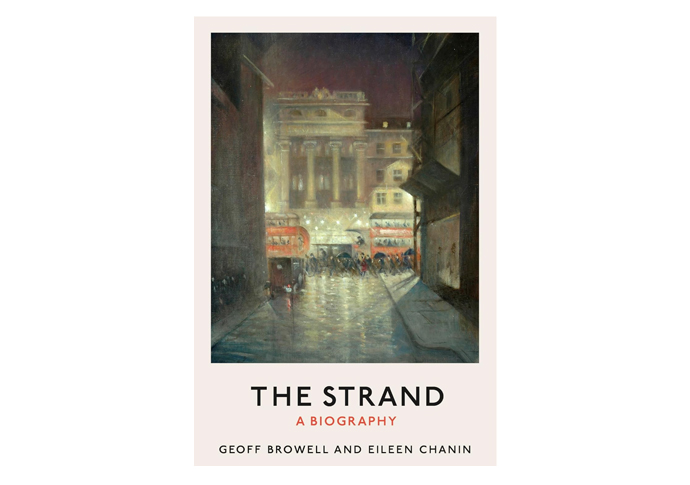

The Strand looking eastward from Exeter Change c1824

“LET’S all go down the Strand,” sang music hall star Harry Castling in 1909. He’d just stepped out the Lyceum Theatre with a friend in tow and instead of turning south down Waterloo Bridge, the suggestion that a good time could be had along that thoroughfare would become a household refrain.

And The Strand has long held a special place in the minds of Londoners, the UK and around the world.

The road, as a new book by historians Eileen Chanin and Geoff Browell explains, a place of dazzling attractions that inspired a music hall star is but one tranche of The Strand’s past.

Layers of history represent the road’s many roles in London’s life. The thoroughfare is a link between Westminster and the City, and has reflected the growth of London: a road boasting aristocratic mansions to where publishers, broadcasters and communicators clustered: a street where scientific instruments were invented, perfected and sold, where groundbreaking thought was pursued and promoted, to a street of music, entertainment and hostelries.

It has, the authors state, a 2,000-year history.

“Arguably, few other streets have been more eventful or influential in the wider world over such a long period,” they add.

The story begins with geological basics. The Strand’s situation on a bend in the Thames gave early Londoners a reason to linger. When the Romans arrived, they built a road along the northern river shore.

“A thousand years ago and since, it witnessed the unfolding of England’s history, and connected the countries; power brokers, the clergy and crown at Westminster to the merchant class represented by the City,” the authors write.

Geoff Browell

We are taken into the street in the medieval strand, which was a “timber-lined gully: noisy, rude and narrow, dark with smoke and stir, enclosed by overhanging jetties”.

The Reformation saw it attract aristocrats seeking a London base.

In 1548 Edward Seymour, first Duke of Somerset, knocked down St Mary’s Church to lay the ground for his magnificent palace, Somerset House.

Somerset seems not to have had much truck with religious superstition: as well as bulldozing St Mary’s, he ordered his workmen to re-use what stone they could, and as a contemporary described: “the bones of many were cast up and carried into the fields”.

He also turned his eye to the charnel house of St Paul’s for material.

This demolition led to his workers gathering up an amazing 500 tons of bones, which were scattered across Finsbury Fields with no care.

Somerset House was one of 11 “mighty mansions”, starting with Essex House in the east and ending with Northumberland House in the west.

It became known as Museum Mile, its riches made up of the aristos’ antiquities and art. During the 1500s and 1600s, The Strand cemented its place as a street of learning: cartographers and globemakers set up shop. It attracted ambassadors and diplomats, drew in visitors from around the globe, and “it buzzed with the prospect of new opportunities, tales of adventure and anticipation of loot”.

It meant The Strand saw first hand the impact of the ever-widening world of Elizabethan times.

One can imagine the interest the average Londoner felt when Sir Walter Raleigh returned to his Strand address, Durham House, with two Native American chiefs, Wanchese and Manteo. Raleigh had his guests with him for nine months and he introduced them to the highest of Elizabethan society. They entertained Londoners by demonstrating how they used a canoe on the fast flowing River Thames.

Eileen Chanin

In the 1600s, its tack switched from homes of the aristocracy to a place of bustling commerce. The New Exchange, a place for upmarket traders and wholesalers, was opened by James I in 1609.

“Its luxury shopping experience was strictly regulated,” the authors note.

Tenants were expected to be of “reputable vocation”, begging and pickpockets discouraged and considerately, a private room was set aside where disobedient servants might be whipped without disturbing shoppers. A bathroom, called a pissing place, was installed and fines were levied for throwing out of the windows “piss or another noisome thing”.

The 1600s and 1700s saw The Strand blossom as a hub for information – which included its eastwards neighbour, Fleet Street.

As the authors describe: “The Strand’s many coffee houses, where different networks intersected, were unofficial knowledge courses: heaven to speculative investors and tipsters alike, those stock jobbing, as well as those after political gossip and debate, or others after more philosophical discussion.”

It went hand-in-hand with the growth of the popular press – and saw such magazines as The Spectator, The Economist, The Strand and Tatler emerge from behind doors on the thoroughfare. John Bell started the Morning Post from The Strand in 1772, while the French Revolution saw its coffee shops and printers clamour in support.

Clubs such as the London Corresponding Society joined other Republican and debating societies at The Strand’s Crown and Anchor meeting room, which held 2,600 people.

And its proximity to Fleet Street saw it be the place to go for early breaking news: WH Smith and Son set up a distribution centre in The Strand, sending bundles of newspapers across the country.

As well as debate, it was a place of invention: cartography and associated instruments were made, and was home to the likes of Jonathan Sissons. He constructed theodolites and sextants. He sold many a telescope by demonstrating its use from a rooftop observatory that boasted views to the Surrey Hills.

Sisson had compatriots working nearby. John Dolland and his son Peter ran the Golden Spectacles and Sea Quadrant. They perfected the refractive lens and built the first telescope to be encased in a mahogany tube. Captain Cook took this, and other scientific instruments the father and son created, as he explored the Pacific.

The street was a place for innovation, and boasted what is believed to be London’s first steam engine. In 1712, a 100ft water tower rose and used steam power to pump water from the Thames.

Drawing on Thomas Newcomen’s machine designed to pump water from mines, it was nicknamed the York Buildings Dragon.

By the 1730s, the fumes and noise were such that it was seen more of a nuisance than a groundbreaking piece of engineering. It covered the area in a smog. The more successful The Strand was, the more people it attracted, and the more people that came, the dirtier, busier, more crime-ridden the street was.

• The Strand: A Biography. By Geoff Browell and Eileen Chanin, Manchester University Press, £25