Review: Pirate Enlightenment, Or The Real Libertalia by David Graeber

In his last book, David Graeber argued that pirates were far more enlightened than we might think

Thursday, 1st June 2023 — By Dan Carrier

Captain Misson was described by Captain Charles Johnson in the 18th century as the founder of the fictional ‘pirate utopia’ called Libertalia

THE accepted view of the period of the Enlightenment is it came out of a burst of revolutionary activity, focusing on western Europe, and developed in debating societies, coffee shops and the rise of a literate population who hungrily consumed political pamphlets.

But it did not blossom in a void – and anthropologist David Graeber, in his last book before he died in 2020, argues the roots of this emancipation was partly inspired by people never usually associated with humanity’s civilised progress.

In Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia, he tells the story of how, 100 years before the French Revolution, motley bands of pirates had settled in Madagascar and had assimilated themselves with the island’s communities.

David explores the stories of these pirate kingdoms, both real and imagined. He states that due to the period of time, the penchant of pirates to tell tall stories and the scarcity of documentary evidence, it is hard to tell the difference between the two: but the fact that this historical narrative exists means it is worthy of study.

“For about 100 years, from the end of the 17th century toward the close of the next, the east coast of Madagascar was scene to a shadow play of storied pirate kings, pirate atrocities, and pirate utopias, rumours of which shocked, inspired and entertained the clients of cafés and pubs across the North Atlantic world,” he writes.

There was the pirate captain Henry Avery, with 10,000 henchmen at his service, who was said to be establishing a new global naval power. Another spoke of a country called Libertalia, set in Madagascar: an egalitarian republic, with no slavery, all goods and food communally shared, and run along democratic lines by a retired French pirate and a defrocked Italian priest.

“Their existence is a historical phenomenon in its own right,” he adds. “There is no doubt that stories about pirate utopias circulated widely. The question is just how widely and how profound those effects actually were.”

He recognises that the “Golden Age of Piracy’ is riddled with myth.

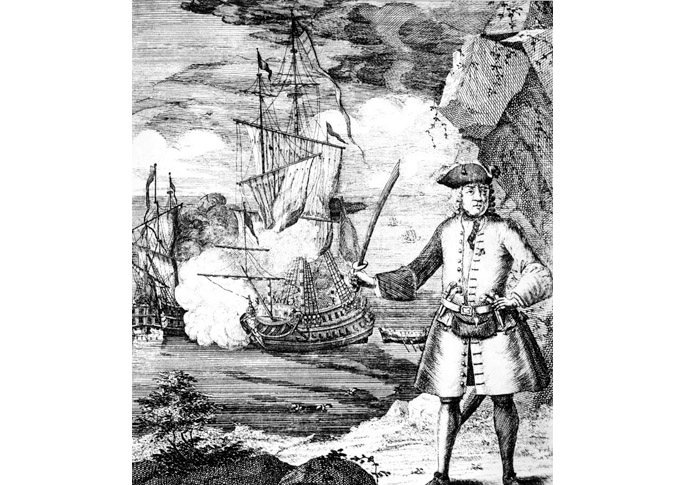

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Avery, with his ship the Fancy shown engaging its prey in the background

“Pirates of that age were so skilled at manipulating legends. They deployed wonder-stories – whether of terrifying violence or inspiring ideals – as weapons of war, even if the war in question was the desperate and ultimately doomed struggle of a motley band of outlaws against the entire emerging structure of world authority at the time,” he says.

That settlements would take on a democratic flavour can be drawn from how pirate ships were run.

Pirate ships were surrounded by stories of daring and terror but on board, affairs were conducted through conversation, deliberation and debate.

“Pirate crews were often made up of so many different sorts of people with knowledge of so many different kinds of social arrangements (the same ship might include Englishmen, Swedes, escaped African slaves, Caribbean Creoles, Native Americans, Arabs) committed to a certain rough and ready egalitarianism, tossed together in situations where the rapid creation of new institutional structures were absolutely required, that they were in a sense perfect laboratories of democratic experiment,” he writes.

On board, leadership came from consent, and the captain’s authority was counterbalanced by the quartermaster and a ship’s council.

“Pirate captains often tried to develop a reputation among outsiders as terrifying, authoritarian desperadoes, but on board their own ships not only were they elected by majority vote and could be removed by the same means at any time, they were also empowered to give commands only during chase or combat, and otherwise had to take part in the assembly like anyone else. There were no ranks on pirate ships, other than the captain and quartermaster,” says David.

“What is more, we know of explicit attempts to translate this form of organisation on to the Malagasy mainland.”

David Graeber

David argues the advent of pirates and their discovery of Madagascar as well situated to escape the dangers of the high seas sparked off societal revolutions along the Madagascan coastline.

David has found evidence that pirates did indeed “create a kind of rebel culture and civilisation that, though surely brutal in many ways, developed its own moral code and democratic institutions.”

Remarkably, their descendants remained and were a self-identifying group.

He argues that the 17th and 18th centuries were marked by a much broader intellectual ferment than is assumed.

“We have every reason to believe that people, objects and ideas from across the Indian Ocean and beyond were regularly making their way to Madagascar,” he writes.

“The island had long been just the sort of place where political exiles, religious dissidents, adventurers and oddballs of the very sort were likely to take refuge.”

David has identified settlements like Sainte-Marie and Ambonavola that were self-conscious attempts to reproduce the pirate ship model on land, with wild stories of pirate kingdoms to overawe potential foreign friends or enemies, matched by the careful development of egalitarian deliberative processes within.

His work shows how 1,000 years ago, Madagascar had various groups settled with little in common with each other – Malay merchants and their servants, Swahili townsfolk, East African pastoralists, refugees and escaped slaves. Archaeological evidence points to this and also that around the 11th or 12th century AD, a cultural movement that can be described as Malagasy emerged.

It would provide a welcoming place for a group who were most unwelcome everywhere else. The dream of a pirate utopia captured the imaginations of the French and British, and this leads David to make a compelling link between this and the dawn of modern thought.

David points out that in 1712, Charles Johnson’s play The Successful Pyrate, about the pirate Henry Avery and his egalitarian community in the Indian Ocean, was popular. Daniel Defoe followed this with his own take on the Avery story.

Around this time, envoys claiming they were from pirate kingdoms arrived in European courtly circles,offering alliances.

David argues the concept of a pirate society was widely discussed across Europe. “The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement uniquely tied to conversational forms, propelled by a faith that all intractable social and intellectual problems could melt away in the clear light of intelligent discussion,” he says.

“Were pirate kingdoms and pirate utopias being discussed in the salons of Paris under Louis XV? It is hard to imagine they weren’t, since at the time they were being discussed virtually everywhere else.”

David asks how these discussions helped shape the revolutionary conclusions reached by many who attended such salons?

How much did these pirate tales shape ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity?

“We can only guess,” answers David. “But if political action is best defined as actions that influences others by being talked about – then pirates and women traders on the northeast coast of Madagascar around the turn of the 18th century were global political actors in the fullest sense of the term.”

• Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia. By David Graeber, Allen Lane, £18.99