Algernon Swinburne: poetry's whipping boy

In the latest in his series on eminent Camden Victorians, Neil Titley considers the poet Algernon Swinburne

Thursday, 26th November 2020 — By Neil Titley

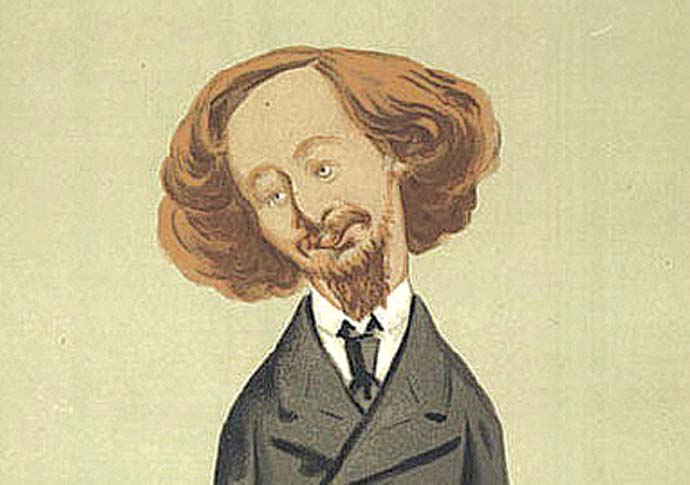

Algernon Swinburne as seen in Vanity Fair

GIVEN their number in current and past cabinets, it may be inferred that an Etonian education is a pre-requisite for benign and balanced government ministers. Whether this applied to alumni before 1900 is open to question. For many, their upbringing walked a fine line between farce and savagery.

The Etonian tradition of flogging stretched back at least to the 1550s when the headmaster was imprisoned on charges of sadism towards his pupils. (He was soon released and Queen Mary I appointed him headmaster of Westminster School instead). In the 19th century, another infamous headmaster received a list of boys who were to be confirmed in chapel. He flogged 56 of them before realising his mistake. One witness added: “If a child wept during a flogging, the other boys were encouraged to beat him as well.”

In at least one pupil this treatment inflamed a latent masochism into a lifelong obsession. Despite achieving international fame for his poetry, Algernon Swinburne (1837-1909) was also a prolific author of flagellation novels which he co-wrote with his cousin Mary. As she shared his tastes, when she married another man Swinburne lost his only real chance of a happy relationship.

In such works as Atalanta in Calydon, Swinburne displayed a dazzling dexterity with rhyme and a very un-Victorian desire to shatter the taboos around such subjects as cannibalism and sado-masochism. Naturally such indiscretion stirred adverse comment from his elders, among them Ralph Waldo Emerson. This particularly annoyed Swinburne. One day he mentioned to a friend that he had responded by post to the revered American sage. The friend replied: “I hope you wrote nothing rash?” “Oh, no, I kept my temper.” “Well, yes, but what did you say?” “I called him a wrinkled and toothless baboon”.

Emerson may well have escaped lightly. On leaving Oxford without a degree Swinburne shared lodgings in Chelsea with the Pre-Raphaelite poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the novelist George Meredith.

However, his personal habits soon started to grate on his housemates. He had a very high-pitched voice that turned to falsetto when excited. One acquaintance said that “his one idea of rational conversation was to dance and skip all over the room, reciting poetry at the top of his voice, and going on and on with it”.

Other than flogging, Swinburne’s most salient mania was alcohol. As he became steadily more crazed with drink, Rossetti was infuriated by his habit of hurtling around the house stark naked and smashing the household china.

Meredith moved out after Swinburne had thrown a poached egg at his head during a literary discussion. He said that he had only resisted kicking Swinburne down the stairs because he realised “what a clatter his horrid little bottom would have made as it bounced from step to step”.

Swinburne even upset his lifelong hero, the writer Victor Hugo, when they eventually met. Having been invited to Hugo’s house in Paris, Swinburne drank Hugo’s health and in aristocratic fashion hurled the glass into the hearth. Never having heard of the custom, Hugo was left grumbling at the shattering of one of his best wine goblets.

After Guy de Maupassant heard a report that Swinburne had indulged in simian bestiality, he was disconcerted to find that his lunch at Swinburne’s Normandy cottage consisted of grilled monkey.

During the 1870s, the Reform League, knowing their man only by his literary reputation, invited Swinburne to stand as an MP. He replied by letter: “I don’t think it is quite my line.”

By 1879, the situation was getting out of hand. Having moved to No 3 Great James St (off Bedford Row) in Camden and now suffering from delirium tremens, Swinburne took to smashing all the windows in his new lodgings and cutting himself badly in the process. Rossetti wrote “all the old lodgers are packing up and leaving”.

Suddenly, a new figure arrived on the scene who was to transform Swinburne’s life. Rossetti’s solicitor was called Theodore Watts-Dunton and his office was on the same street. Watts-Dunton’s first encounter with Swinburne was not propitious. Bearing an introduction from Rossetti, he found Swinburne’s front door open and walked in. Swinburne was again stark naked, performing a berserk dance in front of a large mirror. On seeing the intruder, he drove Watts-Dunton out in a flurry of blows.

Shocked by what he found, Watts-Dunton insisted on removing the gibbering poet to his suburban home in Putney. For the rest of his life Swinburne remained effectively in convalescence under his patron’s surveillance. Under Watts-Dunton’s rules his entertainment consisted of “walking on Wimbledon Common, changing his socks if wet, resting afterwards, and then to read Dickens aloud”.

Swinburne’s health improved but as EF Benson pointed out: “Although he wrote plenty of verse, he never again wrote poetry.”

Despite being nominated for a Nobel Prize for Literature several times, his spirit seemed entirely crushed.

He had always been fond of risqué limericks but now had to consult Watts-Dunton over their use. When one visitor arrived, Swinburne meekly enquired: “Shall I tell Mr Brown about the man from Peru?”

“I think that goes a little too far, Algernon,” came the austere reply.

- Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. For more details go to www.wildetheatre.co.uk