A safe haven

Pre-dating the Welfare State, Youth House in Camden Road was an inclusive sanctuary for young people, writes Victoria Manthorpe

Thursday, 9th May 2024 — By Victoria Manthorpe

Youth House was a 250 Camden Road

A SMALL block of flats now stands at 250 Camden Road and there is nothing left to show of the remarkable social and cultural experiment that for over 40 years was housed in the double-fronted Victorian house that once stood on the site.

Youth House was founded in 1927 by a group of Quakers and Theosophists as “an experiment in communal living based on the ideal of service, a meeting place for young people of all nations, and an opportunity for Youth to gain self-expression along its own lines”.

It combined the facilities of a vegetarian hostel with the recreational and educational activities of a small college, and there were no religious, sex or colour bars. This experiment emerged as a reaction to the carnage of the First World War.

Political and social idealists looked to the rising generation to establish a new international ethos that would prevent a second conflagration. A plethora of youth groups emerged including the Young Friends (Quakers) and The Guild of the Citizens of Tomorrow (Theosophists).

At the same time, there was a swell of initiatives for peace and pacifism from churches of all denominations. The new international No More War Movement, begun in 1921, attracted some leading international figures including Albert Einstein.

Among the founding figures of Youth House were Bernard and Elsie Banfield (both associated with Quakerism) and their brother-in-law the architect Frank Jackman, who converted the house for communal living for 22 residents and staff. There was a large hall for group activities plus a common room-cum-library furnished in traditional club style. The kitchen and restaurant were in the basement.

The young people who gravitated to Youth House were generally office workers, civil servants, young professionals and people with artistic interests. Foreign students, particularly Indians studying at London University, were attracted by the vegetarian diet (rare in those days) and the strands of Eastern mysticism in Theosophy. From the start the atmosphere was convivial, tolerant, and intellectually lively, while the environment was comfortably homely.

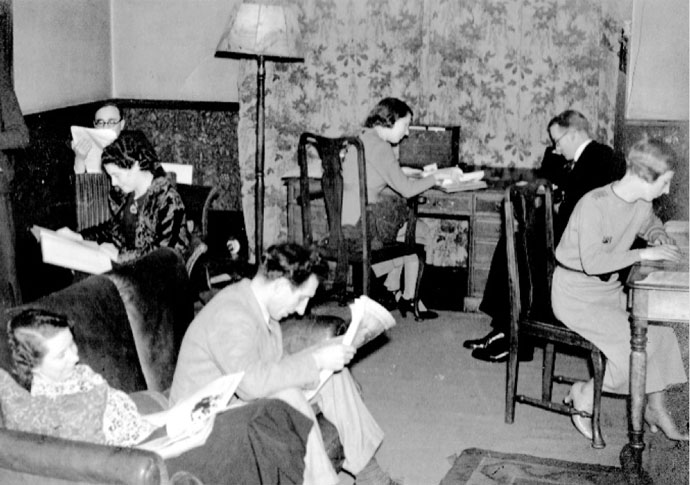

Youth House’s common room in the late 20s or early 30s

Notable among the early residents was the philosopher and spiritual teacher Krishnamurti, who had been raised by Theosophists to become a new World Teacher. Another significant member was Krishna Menon, who founded the India League to champion independence for India, later becoming a statesman of the new government

The social side of the House was vibrant and many friendships and romances blossomed. There were dances, plays, concerts, lectures, language classes, and morning meditations as well as more informal debates, and discussions. Sympathetic speakers included Michael Foot talking about the Labour Party and Michael Tippett on music.

During August every year, the building was opened up as a hostel for international visitors (one shilling a night) and the main hall was filled with bunk beds to accommodate them. In line with the European trend, Youth House promoted healthy outdoor living through “tramps” – long walks, often all night – and hiking and camping holidays.

While some British members of Youth House manifested their internationalism by making regular trips to Europe to foster friendships, other European members had already fled from incipient Nazism.

In 1938 Bernard and Elsie Banfield, rented a pair of old canal workers’ cottages near Tring and, with financial help from the Society of Friends, began taking in refugees from central Europe, mostly Jews.

This endeavour was supported communally by guaranteed weekly donations from the Youth House members and by their voluntary work, with Elsie Banfield supervising the cooking and housework.

At Youth House there were no sex, religious or colour bars

When war eventually came the Youth House members went their various ways, some to bear witness to their pacifist beliefs as conscientious objectors, or in various non-combatant roles. Others decided to support what was widely viewed as a “just war”. Many of the refugees were interned.

During the war, Youth House continued to provide a London base for its members under the secretaryship of the author Denys Val Baker.

In 1937, Richard Titmuss, an organising member and pioneering social researcher, had written: “The purpose of Youth House… is to produce rebels who would willingly conform to what little is sane in society today but who would rebel against all that is cruel, unjust, stupid and tyrannous.”

But that purpose was knocked sideways by the Second World War and to some extent addressed by the Welfare State that he helped to found.

Youth House lost its raison d’être of forestalling European conflict, although internationalism continued to have its ardent followers.

Gradually, Youth House became simply a shabby, if well-loved, hostel until it was closed in the late 1960s – ironically as a new youth movement was on the rise.

While researching a book on two generations of conscious objectors in my own family, I realised that very little had been written about Youth House in its heyday. My parents had met there in the 1930s so I looked for sources of memorabilia among the children of their contemporaries and was fortunate to find that some had been saved.

• For a fuller account see Different Drums: One Family, Two Wars, published this month by Poppyland Press. www.poppyland.co.uk