A people’s champion: Henry Sharpe’s donkey war

Newly unearthed journals cast light on Hampstead in the mid-19th century, written by an unusual businessman who sided with the poor and challenged a rich landowner who sought to develop the Heath

Friday, 5th September 2025 — By Dan Carrier

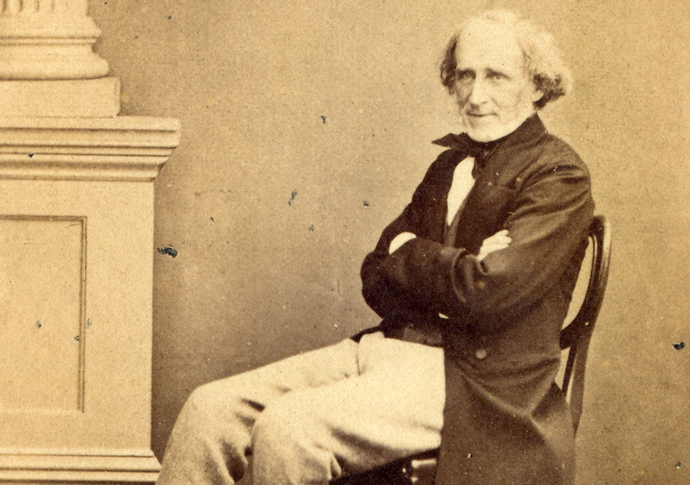

Henry Sharpe

THE boxes had lain on a shelf, untouched for three decades. They contained the papers of a Hampstead businessman, Henry Sharpe, written between 1830 and the end of the 1840s.

And when historian Helen Lawrence began trawling through the papers inside, she found a treasure trove that sheds new light on life in Hampstead at a vital period of its development.

Helen, former chair of the Heath and Hampstead Society, had been researching her book How Hampstead Heath was Saved: a story of ‘people power’ when the former Camden borough archivist Malcolm Holmes referred to the Sharpe collection which had been donated to the archive in the 1980s and stored, unread.

Helen discovered “a large sheaf of typed papers: The Journal of Henry Sharpe, who lived between 1802 and 1873”.

She says: “What it contained was not only of immense significance to the history of Hampstead Heath, but was also a valuable historical document in its own right.”

The journals had been typed up by Henry’s grandson Eric, a furniture maker in the Arts & Crafts tradition, and eventually ended up in the safe keeping of a friend and fellow furniture maker, Oliver Morel. They were then handed on to Malcolm Holmes.

They begin with a statement: “25 January 1830i: Resolved to keep a journal, as the best check against wasting my time, by enabling me to look back on former resolutions, as to my conduct and also by seeing what long periods are passed without any real advantage to myself to stimulate me to employ it better.”

George IV was on the throne and Henry, 27, had recently set up a business with his brother Dan to trade with Portugal.

This first journal did not last more than a few months, but he returned to it 10 years later, by now married and with a family.

It’s a fascinating look into the minutiae of Hampstead life in the mid-19th century, and there are important kernels in his story that shed light on wider issues.

Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson

Henry’s equitable nature saw him take the side of a group of working-class donkey owners who plied a trade on the Heath on a Sunday, offering rides. They were challenged by magistrates and pious groups seeking to protect the Sabbath. Henry felt it grossly unfair and acted on their behalf. It would lead him to involvement in protecting the Heath at large, and his journals offer a preview into the battle that would erupt when the Hampstead land owner Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson sought to develop the Heath.

The Sharpes moved to Elm Row, Hampstead in 1841. Hampstead village soon charmed them: “I have to ride to town every day taking an hour each way, but it cannot be considered lost time as I have a pleasant chat with my neighbours and it seems to agree with me wonderfully as I am growing quite fat.”

That December he remarked he had spent a beautiful day on the Heath with his children, who had enjoyed donkey rides. It was the beginning of a long relationship with the men who grazed their donkeys and earned a few pennies offering rides.

In February 1842 he notes: “We heard…there is to be an attempt to put down donkeys on the Heath on Sundays, which I firmly oppose.”

He was furious.

“I fear the object will be obtained as it is supported by those who want to keep the Sunday more strictly and those who are troubled by the noise of the Londoners and the vulgarity of the donkey boys; but with both it is in fact only the war of the rich against the poor, as the Heath can be enjoyed by gentlemen in the week but by the working men only on Sundays.”

The donkey war began in earnest by July that year, with Henry taking matters into his own hands.

“Last night I had a note from Pryor the Magistrate telling me the owner would be fined if we had a donkey ride again as we did last Sunday…I shall certainly take one next Sunday and see what will happen,” he adds.

“It is a monstrous thing that a poor man (I do not mean myself) should not be allowed to take a 6d ride on a donkey when a rich man may ride on his horse, or indeed when a man may hire a horse if he can afford it.”

Donkey rides were being challenged under The Lord’s Day Act, which prohibited some Sunday trade – so Henry took legal advice. He wrote to the Hampstead magistrate to inform him he would be taking a ride and “would advise the men not to pay fines”.

The public drinking fountain put up by Henry Sharpe, pictured in 1909

He discovered the following week that grazing donkeys had been rounded up, citing a rule conjured up by Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson about rights to graze on the common land.

He used his standing to directly speak to Sir Thomas. “I repeated my objection that a man had as much right to hire a donkey for 6d as another a horse for a guinea,” he writes.

Sir Thomas’s angry reply was the result of the opposition he knew he was facing when it came to building on the Heath: “He is furious against the Hampstead gentry and for their opposition to his estate bill, abuses them in good round terms and says he will not take any more trouble to pleasure their fancies about donkeys…”

It was a harbinger of bigger battles to come to protect the Heath for everyone.

“Sir Thomas Wilson’s estate bill is exciting the Hampstead people very much, everybody being alarmed at the idea of the fields round the Heath being built upon. He has written a couple of very silly circular letters about it; not stating out boldly what it is that he is doing; and he loses character by the transaction,” notes Henry.

In October 1844, Henry recorded a visit to Sir Thomas. “I found him over his wine with a man, apparently a surveyor come up to make arrangements about the building he intends to do.

“He could talk about nothing else and was… altogether not agreeable. He is a pretty instance of how little riches contribute to a man’s happiness; here he is with perhaps £10,000 a year going to put himself to all manner of trouble and vexation, probably for the rest of his life, in order to add perhaps a couple of thousand to it, having all the while no family to spend it on or leave it to.”

Such miserliness went against Henry’s own works: as the book reveals, he helped found a school, kept the Hampstead subscription library going through tough times, put up public drinking fountains and provided seats on Hampstead Heath.

The period, as Helen explains in accompanying notes, was a maelstrom of change: the ills of the Industrial Revolution were pronounced and Henry saw it all.

While he did not question the rigid class society of Victorian England, as Helen explains, “his sympathies were with the oppressed and the poor.

“He risked putting himself at odds with his neighbours by opposing their attempts to suppress the donkey rides, because he saw through their efforts – the rich trying to tyrannize the poor.

“But through his sincere and constant diplomacy, both the gentry and the donkey men came to respect him.”

• The Journals of Henry Sharpe: City Merchant and Hampstead Worthy 1830-1847. Edited by Helen Lawrence. Published by Boydell and Brewer on behalf of the London Record Society

• The London Record Society, Camden History Society and Heath & Hampstead Society are launching the book at St John-at-Hampstead Parish Church, Church Row, NW3, on Monday September 15, 7pm.